Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

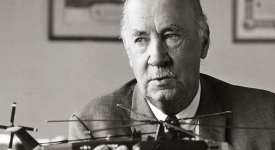

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

One year on from the Euromaidan revolution

Ukraine Business Insight,

Ukraine Business Insight,

Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, December, 5, 2014

U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC),

Washington, D.C., Wednesday, December 5, 2014

Ukraine’s strategic location between East and West has often caused the country to be invaded, and it is in dire straits once again with no early end to its troubles in sight. The country has been partly dismembered with the de-facto loss of Crimea, and Russian-backed separatists continuing to wage war on its territory; international reserves are critically low at just US$ 12.6 billion, and the Hryvnia exchange rate is falling through the floor.

The country is now a nexus of East-West power-plays, and the key actor in deciding Ukraine’s future is Russian president Vladimir Putin - an authoritarian figure wary of the West, who regrets the break-up of the Soviet Union and believes Ukraine must be part of its sphere of influence, if not actually part of Russia.

But it’s no misty-eyed reminiscence. Just as ISIS rejects international law and boundaries as it seeks to re-write history in the Levant, so Russia is doing the same in Ukraine – its historic borderlands. Despite neither recognition for Crimea’s annexation, nor international acceptance of the separatist plebiscite in rebel controlled areas, Russia continues to destabilise the country and notwithstanding the shaky ceasefire in Eastern Ukraine, Donetsk airport remains under siege, while Russia’s military continue to ignore the border.

It is just over a year ago that former President Yanukovych abandoned a widely supported policy of pursuing a political and free trade agreement with the EU, and instead favoured the Russia-led trading block. This unexpected move, prompted by the promise of a 30% cheaper gas bill and a US$ 15 billion aid package plus rumoured threats from Russia, delivered a reversal of policy that undid years and $billions of US and EU promotion of democracy and a western orientation in the country.

It is true that an elected government was subsequently overthrown by ‘the mob’, furious at this betrayal, that a minority group of right-wing Ukrainian nationalists were involved, and that the resulting interim government made mistakes in its policies toward use of the Russian language in Ukraine, which fuelled divisions at a time when the authorities should have been building bridges. But the characterisation of the ‘people power’ Maidan revolution as a right-wing coup is pure fiction, just as the suggestion that the well-equipped and professionally-led overthrow of authorities in Crimea or within the Donbas were spontaneous. The truth in both cases is the opposite. But truth is now a matter of perspective and whose truth you chose. As a consequence, most of Ukraine’s banks are collapsing. Public debt is forecast to double to some 80 percent of GDP this year and inflation is predicted to rise to 24 percent this year and higher in 2015.

Now the revolution needs to avoid turning on itself, with the Ukrainian President Poroshenko, who only recently renewed his mandate via parliamentary elections on October 26, being heckled at a memorial ceremony for the 100 protesters killed in Kyiv’s Euromaidan revolution. As an oligarch himself, Poroshenko was unlikely to have been a pin-up for those who died in the Euromaidan tide of anti-corruption, but he remains arguably the most palatable of those with the ability to galvanise a government of National Unity to fight for the country’s territorial integrity.

The Rada’s young, inexperienced, newly elected politicians are largely untainted by corruption but face the most daunting of challenges - a country with foreign troops and separatists, another region entirely occupied, and most businesses owned by oligarchs not so much tainted as born of corruption.

Playing real-politik, the question remains, what deal can be done short of a military solution? Or has Putin already decided that he will continue to pursue a proxy or overt military route? Recognition of a Russian Crimea would not be enough on its own, as it is not economically viable, and a costly fixed link across the Kerch Strait to the peninsula would take both time and money. The coastal area by Mariupol does not support the separatists and its capture would ensure ongoing instability in the area, even if it made it a more viable entity, especially given potential oil reserves offshore.

So while sanctions are hurting Russia financially, Russia has a huge capacity to absorb such pain – if Putin can keep a lid on opposition from his own oligarchs – but the main issues for Putin are, what exactly is he required to do to end sanctions? And, is the US prepared to actually fund a war against Russia? A US$ 53 m package of non-lethal military equipment from the US was announced in September, and Kyiv is now pushing for further support including weaponry. Alexander Zakharchenko, the Donetsk rebel leader, said in August that 3,000 to 4,000 Russian citizens had been fighting alongside the rebels. And satellite evidence contradicts Kremlin denials of supplying troops and military hardware to the rebels, an activity U.S. Vice President Joe Biden described on Friday as a “flagrant violation of the bedrock principles of the international system.”Conversely the ‘spheres of influence’ issue is not entirely one way, with a leaked recording of an alleged private telephone conversation between US Assistant Secretary of State Victoria Nuland and US Ambassador to Kyiv Geoffrey Pyatt appearing to confirm the US playing a more subtle game, working with Ukrainian opposition parties to achieve a Ukrainian government that was in agreement with US interests. The US has also been increasingly economically engaged with Ukraine signing a US$10 billion shale gas deal with US energy giant Chevron to potentially end Ukraine’s energy dependence on Russia by 2020. Chevron would explore the Olesky deposit in Western Ukraine that is estimated to hold 2.98 trillion cubic metres of gas.

Some, such as Dr Nafeez Ahmed, executive director of the Institute for Policy Research & Development , would argue that cold war never really ended, and Ukraine’s role has changed little since Professor R Craig Nation, Director of Russian and Eurasian Studies at the US Army War College's Strategic Studies Institute, described the situation more than a decade ago: "Ukraine is increasingly perceived to be critically situated in the emerging battle to dominate energy transport corridors linking the oil and natural gas reserves of the Caspian basin to European markets... Considerable competition has already emerged over the construction of pipelines. Whether Ukraine will provide alternative routes helping to diversify access, as the West would prefer, or 'find itself forced to play the role of a Russian subsidiary,' remains to be seen."So the crux is a US/Russian standoff, with the Ukrainian people being torn apart in the process – unless they quickly unite behind whatever future they really want.

On the positive side Putin has backed the Minsk peace deal and agreed a deal to resume gas supplies to Ukraine. Plus Ukraine did manage to hold free and fair parliamentary elections on October 26 in those areas not under rebel control. Now the three reform-minded winners need to work together.

In a blog on the Peterson Institute for International Economics, Anders Aslund calls for urgent radical action, describing the draft coalition agreement as an old-style bureaucratic Soviet document for the preservation of the old system, and he urges that three major reforms to be carried out quickly: “First, energy prices have to be unified at an international market level… to cut harmful public expenditures and eliminate the main source of top-level corruption. …it is a matter of national security and sovereignty since the Kremlin controls this corrupt game.“… cut public expenditures by about one-tenth of GDP in 2015. The cut in energy subsidies would do most of the job. “The third reform would be to finally legalise private sales of agricultural land. Otherwise, the current agricultural boom is not likely to continue but hit a ceiling. (A proposed coalition agreement released on November 14 suggests that the moratorium on private sales of agricultural land be prolonged until 2018).

The above policies would likely hit the Donbas region, where the separatists are located, disproportionately because it is the area of old subsidised heavy industry including coal and steel. So achieving consensus will not be easy. From a Western perspective, it’s difficult to believe that that Putin’s embrace could be enticing. But to support painful reform today for a better future tomorrow requires a leap of faith – and in Ukraine right now no one truly trusts politicians of any party to deliver.

LINK: http://www.ukrainebusinessinsight.com/news/310/One_year_on_from_the_Euromaidan_revolution