Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

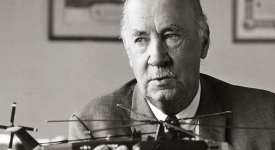

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Remarks by Ambassador Pyatt on the Future of U.S.-Ukraine Relations

Press office of the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv

Press office of the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv

Mon, March 14, 2016

MODERATOR: Dear ladies and gentlemen, of course the Ambassador will speak, but first several words from me. First of all, this is a great honor for me to moderate this meeting, because I am not very often present at conversations where on both sides there are such distinguished people. That’s why I will be mostly silent during the conversation, because I will have to listen. However, I will watch very carefully who wants to ask a question of the Ambassador, and Anastasia will then pass the microphone to those people. The very polite requirement is to please introduce yourself, also to provide the Ambassador with an even better idea after that initial presentation who you are, and what you are.

I talked to some of the people present here before the meeting, and from what they told me I gather that the three key issues that they are interested in hearing from you is the U.S. assessment of the state of the reform process in Ukraine, then, what the changes which are going to happen – or maybe not – in the United States and in Ukraine are going to bring into our mutual relations, and, as there are many people who actively develop business and economics in Ukraine, what is the state and prospects of U.S. – Ukrainian business and economic relations. However, this is just an outline. I was not able to talk to everybody. I hope that those people whose questions I did not mention will ask them.

I asked the Ambassador whether he wanted to make a keynote speech. “Oh, no, no, no,” he said. There will be some opening remarks, because as I gather he is very eager to listen to you – drawing his own conclusions from your questions. So, without much further introduction, the Ambassador of the United States, Geoffrey Pyatt. Your opening remarks.

AMBASSADOR PYATT: Well first of all, thank you, Andriy. Thank you to all of our partners at Hromadske.tv for joining with us in this event. It is a huge honor and pleasure for me to be back at Kyiv-Mohyla. It’s a special surprise and an honor to have Minister Kvit here. He will remember, certainly I remember, our first meeting happened, I think, in my fourth day in the office here in Ukraine. And we sat down in his office, and at one point he said to me, “You know, Ambassador, I really think Ukraine needs another revolution.” And I didn’t pay enough attention to that comment at the time – in 2013.

And then of course, my first public address in Ukraine was also here at Kyiv-Mohyla, so Mr. President, thank you very much for having me back. It is a special privilege any time I am able to sit down and speak with Ukrainian young people, because you really are the foundation on which America’s hopes for building a modern, democratic, European state here rest – especially because of the special relationship that the President alluded to between the Ukrainian diaspora in the United States and Americans who have been so supportive of Kyiv-Mohyla and the renaissance that this institution has gone through since Ukrainian independence. So it really is my honor to be here with you today.

As Andriy said, I really, truly want to have a conversation. The first time I came here, it was up on a big stage, and everybody was down in the audience, and it sort of felt like a university lecture. I’m hoping that this can be much more of a conversation. So I would encourage people not only to put questions to me, but really let me know what I’m missing. The foundation of American policy toward Ukraine is support to the people of Ukraine. You are the ones who will make the decisions about your own future, so I’m eager to use this afternoon as an opportunity to continue that conversation, and I certainly will get into the three questions, Andriy, which you posed to me.

As I said, it’s been three years almost now since the first time I came to speak at Kyiv-Mohyla, and what a three years it’s been – an extraordinarily historic period in this country’s evolution. Certainly, from where I sit, a period that has created the best possibility that Ukraine has ever had to anchor itself in Europe, in European institutions, in European values, and those are goals that the United States emphatically shares.

When I was here three years ago – and getting ready for today, I went back and re-read my words from that address in October of 2013 – and of course, the great debate then was, was Yanukovych going to sign the Association Agreement, and what was going to happen to Yulia Tymoshenko. And as I re-looked those remarks, it teaches you to be very humble about making predictions about Ukraine, because so much has changed. And in many ways, I would argue that this is a completely different and much more optimistic scenario.

You look at what’s changed. You’ve had three good elections – the freest elections that Ukraine has ever had. You’ve selected a new Rada, which includes – as you pointed out – a number of Kyiv-Mohyla graduates, which has a critical mass of young people who are new to politics and are committed to building democratic institutions that are answerable to the Ukrainian people, so that government serves the citizens and not the other way around. You’ve implemented your Association Agreement – the big question mark that hung over Ukrainian politics in those days three years ago has now been answered. Ukraine is anchored in European institutions through your signature of the Association Agreement, your DCFTA, and the clear commitment to move toward European values and European standards of rule of law.

You’ve stabilized your economy, you’ve rebuilt your reserves, you’ve stuck to your IMF agreements. As painful as that’s been, it’s incredibly important as a demonstration of the Ukrainian leadership’s commitment to root out the habits of corruption that have done so much in the past to hold this country back. And you’ve begun to build new institutions – none more important, I would argue, than the new patrol police, which the United States has helped to establish, and which plays such an important role in my mind in helping to rebuild the faith that the Ukrainian people have in their government institutions, which is, I think, one of the most valuable assets that the patrol police has managed to establish – that confidence, and that trust. You can’t put a price tag on it, but it is key to building democratic governance and helping to build a sustainable future for this country.

Obviously there are many challenges, and I’ll talk a little bit about that this afternoon, but I honestly believe that 2016 should be the year in which Ukraine – Ukraine’s leaders, Ukraine’s politicians, the Government, the President, and all of you – can build the institutions and the practices which guarantee that there is no going back, that Ukraine won’t need another revolution, that there won’t be further cause to doubt Ukraine’s place in Europe and among the European family of nations, to make the changes that have occurred in this country irreversible, and to guarantee that Ukraine never again will have to suffer under the kind of authoritarian, post-Soviet regime that characterized the Yanukovych period when I first arrived here.

You know, one of the great privileges of my job is that I get to travel around Ukraine a lot. I think I’ve seen more of Ukraine than most Ukrainians. I’ve seen the spectacular sea cliffs of Crimea. I’ve been to the top of Hoverla, the highest mountain in Ukraine. I’ve seen the sunflower fields of Donbas at the peak of the summer, when they come up higher than your head. I’ve seen the coast of Bessarabia, spectacular Ottoman-era forts and the surf crashing in this spectacular piece of geography that has marked so much of Ukraine’s history with different empires and different political forces that have shaped what you have become today.

And one of the most powerful impressions that you take away from those travels is the Ukrainian people. The greatest strength of this country is its human capital – its civil society organizations, your culture, your pride, the deep sense of patriotism that the bitter experience of the past two years has helped to reinforce. That can’t be taken away from you. And it’s what makes me so optimistic about Ukraine’s long-term future, and your question, Andriy. Ukraine should be a very wealthy country. You have all the ingredients in terms of human capital, technological expertise, natural resources – some of the most bountiful agricultural lands that God has placed anywhere on the globe. What you have lacked is governance, and for me, that is the key of the Revolution of Dignity – the promise of better governance that unlocks the potential of this country.

You asked, Andriy, about reform, and how is that process coming. And I’m eager to hear from all of you. I suspect many of you will say that reform hasn’t moved fast enough. I hear that from Ukrainians every day. What is most striking to me though, and what’s important to me, is not to lose track of the progress that has been made – to recognize the improvements that have occurred, and we’ve talked about some of them. You can also look at things like the energy sector, the fact that this is the first winter in the history of independent Ukraine when you’ve bought no gas from Gazprom. You have truly achieved energy independence. And I think that the challenge is not to lose your optimism, your confidence that you can prevail in this effort.

I spoke to one member of the Rada – one of these young members of the Rada – and they said to me, “You know, Ambassador, this is like running a marathon, but the problem is every time you think you’re running the last lap, somebody rings the bell and says, ‘no, you’ve got one more lap that you have to run.’” And my message to you is to be confident that if you do that, if you stick to the path of reform, the United States, your other international partners in the G7 will stand with you, because we want to see Ukraine succeed. We, the United States, have a powerful interest in Ukraine’s long-term success. As Vice President Biden has said, you can’t have a Europe whole, free, and at peace unless Ukraine is whole, and free and at peace. So we are committed to assisting you in this effort, but the hard work has to be done by Ukrainians. More than anybody else, it needs to be done by the people in this room – by the new generation who are coming into politics, people who have no experience with Ukraine’s terrible Soviet history, who come out of a European tradition, and who are committed to building in this society the same kind of democratic, rule of law institutions that have brought prosperity to so much of the rest of Europe.

Two last quick thoughts that I would leave with you. In this process of consolidating reform in 2016, I think one of the key benchmarks will be the work that’s being done on constitutional reform and decentralization, which has become very political and very controversial in the Rada. But as a practical matter, when I talk to Ukrainians and especially when I travel to cities – whether it’s Lviv, or Vinnytsia or Dnipropetrovsk, or Kharkiv – you talk to local people and they have an instinctive interest in decentralization. They say yes, we should be able to make our own choices, whether it’s on police, or education, or road maintenance, or all the other things that are part of running a city or a community. So I think one of the tasks for this year is to consolidate this process of decentralization, to build capacity.

I don’t worry about the ability of the administrations in Kyiv or Lviv or Vinnytsia to manage the responsibilities and the resources that come with decentralization, but what about Slovyansk? What about small cities in Zakarpatska [oblast]? That’s where the real challenge is going to be faced. In that regard, the United States has been a strong partner. Our USAID is committed to working with municipalities to help them execute these responsibilities. But these are all important parts of delivering governance, and it comes back to that fundamental principle that I started with. To build a Ukrainian government that exists not to enrich one family, that exists not to protect particular oligarchic clans, but that exists to serve the interests and desires and hopes of 45 million Ukrainians. I think that goal is more within reach today than it has ever been before. It’s also a goal that the Ukrainian people deeply deserve, because you’ve worked very, very hard for it.

The other issue that I want to say a brief word on – and I’m sure it will come up – relates to the war in the east and Russia. The United States is very clear that there is a victim and an aggressor in this conflict. One of the things that will stick with me from my time in Ukraine is an impression of the extraordinary courage that Ukrainian soldiers, that Ukrainian civil society, Ukrainian volunteers have demonstrated in fending off this war of aggression that the Kremlin brought to your country. I think the challenge now is to consolidate peace through the Minsk agreement, to deliver good governance for all of Ukraine, to include the occupied territories.

I met this morning with a Ukrainian journalist – a woman from Luhansk – who was held hostage for more than a year, and we were talking about her experience while she was in captivity and the terrible suffering that she went through. But she also described to me her experience as a prisoner, and how her captors were trying to convince her that she needed to understand that Russian speakers were in danger in Ukraine, that NATO battalions were threatening Ukraine, and she said to me at one point, “I almost started to doubt myself, because they were so insistent.” And I think what that gets at is the point that ultimately the greatest weapon in Ukraine’s confrontation with the Kremlin is right here in this room. It’s the success that you all are going to achieve in building a democratic, rule of law society, which puts to a lie all of the propaganda that has come out of the Kremlin and out of its agents in DNR and LNR to mischaracterize what you stand for and what you are trying to achieve.

I am very confident that that goal is within reach. I’m also confident that the United States, our European allies – France and Germany as leaders of the Normandy group – will stand with Ukraine also. As long as you continue to implement your side of the Minsk bargain, we will make sure that Russia is held to account for what it has done, its violation of your territorial integrity, first in Crimea with the invasion, and thereafter with this terrible, terrible war which has produced more than 9,000 casualties in Donbas.

In this regard, and I’ll finish up, I would really applaud the effort, as the President was explaining to me, that Kyiv-Mohyla has made to establish a faculty and a program in post-traumatic stress and rehabilitation. It is so, so important that the Ukrainian volunteers and soldiers who have fought in the east be properly assisted with their reintegration to Ukrainian society. So Mr. President, thank you for what Kyiv-Mohyla is doing in that regard as well.

So Andriy, I’ll stop with that. And as I said, what I really hope to have this afternoon is less of a university lecture and much more of a conversation. And I’m delighted to be able to do it in this beautiful room that is so evocative of the incredible history that this institution has.

MODERATOR: I think you have preempted a lot of questions that may be raised in this audience, but still, of course, it is impossible to look ahead and guess every question. Why I am insistent on the word question? We call on you to not make just statements, because then the Ambassador will probably not comment, and the conversation will not be a two-way conversation. So yes, your assessment is welcome, as I gather from the words of the Ambassador, but please finish your remarks with a question to our guest. Meanwhile, as I see no raised hands… Yes, please…

QUESTION: Your excellency, you know that Ukraine survives a deep political crisis today, and overcoming of this crisis lies not in personalities – it doesn’t matter the surname Jaresko, Yatsenyuk, or Groysman or anyone other – but overcoming of this crisis lies in structural reforms of existing political system, oligarchic system. Up to you, what should be done to change this existing political system and in order to overcome the crisis in order to renew the trust of people, of parliament, and to renew the normal way of coalition government.

AMBASSADOR PYATT: That’s a terrific question. Thank you for it. Obviously vitally important.

MODERATOR: We’re hoping for a terrific answer.

(Laughter)

AMBASSADOR PYATT: I’ll give it my best shot, Andriy. Soon after his resignation, Minister Abromavicius talked about the Rada and all of you and your colleagues. And he said, half of them are there to reform and build a new country, and half of them are there to make money. I can’t dispute his assessment of the balance, but I will tell you that’s 50% better than when I came to Ukraine in 2013, and that’s what makes me so hopeful. That you now have a Rada where there is a critical mass of Rada members, a lot from your party from Samopomich, but from all political factions – literally every single political faction has members of this new generation who are committed to reform, who are not there to work for one oligarchic group or another, but in fact are there to build a new country.

And so, the most important thing is don’t give up. Keep at it. Keep doing what you’re doing. And know that in fighting against this oligarchic politics, all of your international partners want you to succeed. We all recognize that Ukraine’s long-term prosperity and stability rests on breaking the back of this model of oligarchic politics which was the legacy of your Soviet history, and which was also, I think to some degree, a function of how Ukraine achieved independence.

Somebody who is not a politician, but who I respect a lot, said to me, “You know, Ambassador, our problem as Ukrainians is that independence just fell into our lap. Twenty five years ago, we just woke up one morning and suddenly we had it. It was there, but we never had to work for it.” And he made the point to me, he said, “But now we’ve had to work for it. We had the Maidan, the Heavenly Hundred, and now this confrontation with the Kremlin. So we’ve all made incredible sacrifices. We have to deliver now. We have a sacred obligation to deliver on that.” I would agree with that friend. I think there is, as Vice President Biden said when he was speaking with all of you in the Rada, you all have a sacred duty – not just to the Ukrainian voters who put you into office, but to all the people who have made so many extraordinary sacrifices over the past two years.

I think you’re also exactly right that when people focus on Yatsenyuk, Jaresko, Groysman, that’s the wrong question. It’s not who, but what. The most important thing at this point is a clear understanding of the agenda of reform that lies before Ukraine, agreement among the political factions to support and implement those reforms. And when I say the political factions, it really is everybody. Part of what, I think, has created this impasse is that you have large portions of parties that are part of the governing coalition who themselves began to rebel against the reform agenda. My view is you have come much too far to give up all the hard work that you’ve done by now backsliding on the reform process.

Some times in life, when you’re climbing up a mountain, you get close enough to the top, and it’s much safer to get up to the top and go down the other side than to try to back your way down the ropes. To me, that’s what it feels like – the moment that Ukraine has arrived at. You’ve made real progress, and again, I would give enormous credit to you and others in the Rada who have pushed for legislation in areas like privatization, like freedom of information, like financial disclosure – all of these structural changes that make it harder for these oligarchic mafias to do their business. And you just need to keep at it, and in doing so, you will have the strong support of the United States.

MODERATOR: Thank you. And another question from the second row. Please.

QUESTION: Barack Obama gave an interview to the Atlantic magazine. I know you are well aware of that. And he softened his position on Russia, I guess. And, what is he saying about Vladimir Putin right now is the following, that he is constantly interested in being seen as our peer and as working with us because he’s not completely stupid. And basically, the U.S. is more interested in Chinese topic right now. How would you explain this more, like, soft position?

AMBASSADOR PYATT: Thanks. It’s a really important question, and I’m not going to try to parse President Obama’s words. What I would emphasize to you is that President Obama has been very clear on our views of Russia’s actions in Ukraine. I’ll say, sitting here at the university, I think you have been lucky that right now we have an American president who is a constitutional lawyer and a scholar, because I can tell you he has had a very scholarly black and white view of Russia’s actions in Ukraine, Russia’s violation of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. He has made extraordinary efforts to exercise international leadership, working with our European partners first to ensure a resolute reaction to the illegal annexation, the invasion of Crimea, and thereafter to maintain unity on sanctions as regards Russia’s aggression in the east. I think that’s one of the things that surprised Vladimir Putin.

There are a lot of things that surprised him. I don’t think he counted on the strength, the resilience of the Ukrainian people. It really felt to me, in the spring of 2014, when you had Kharkiv and Odesa and all the rest of this like the Kremlin thought they could crack Ukraine wide open. That didn’t happen. I don’t think he counted on the military resilience of the Ukrainian armed forces and how you were able to organize yourselves over the summer of 2014 to limit the movement of Russian and separatist forces. But I also don’t think he counted on the unity of the international community, the fact that the United States, our G7 allies, and all 28 European Union member states have been so firm on the principles of sanctions and the very clear requirements for the relaxation of those sanctions. So I would, first of all, highlight the importance of his very clear view on Russia’s actions in this country. I would also note the really extraordinary actions on a bipartisan basis – Republican and Democrat – that the United States has taken to support the Ukrainian people through our loan guarantees, through our military and security assistance, through our economic and technical assistance, all of which is a vote of confidence not in any one political personality or political party, but in all of you, the Ukrainian people.

Ultimately, all we can do is help. You have to do the work. That’s very clear. But I know you all know that, and you have demonstrated over the past two years that you are prepared to do so. But as Vice President Biden has pointed out on many occasions, and as he was very clear on when he spoke to the Rada, if Ukraine sticks to the path of reform, the United States and our allies will be by your side in helping to ensure your success.

MODERATOR: Thank you. The Russian factor, which was discussed right now, is sometimes a thing that we may put the blame on for almost everything. And we often speak of Russia as our northern neighbor. There is a northern neighbor of the United States.

[Crosstalk]

So the next question comes from your northern neighbor, but from a graduate of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

QUESTION: What do you think about the peacekeeping mission in the east?

AMBASSADOR PYATT: Really good question. [Crosstalk] We just had yesterday a terrific visit to the White House by Prime Minister Trudeau. President Obama has a wonderful – they have a wonderful partnership – it’s a very deep and positive relationship. Our relationship with Canada is as close as we have with any country in the world. One thing that I’m very proud of is that we’re able to have that kind of close cooperation with our Canadian allies here in Ukraine as well. I’ve got a wonderful counterpart in Roman Waschuk. I had not realized that he had a connection to Kyiv-Mohyla, so I’ll point that out to him next time.

We are also working very closely with Canada in our support to the Ukrainian armed forces. The United States has already committed $266 million in security sector assistance. We’re going to grow that quite a bit more over the course of this year. I am convinced that by far the most important military assistance we have provided to Ukraine is not the radars or the night vision devices or the Humvees, it’s the training that we do out at Yavoriv, for reasons that all of you here at the university will understand very well – the most valuable asset of any organization is the people. I’m very pleased that it’s not just Americans and American army soldiers, but also Canadian counterparts. This has been a very high priority, I know, for the Canadian armed forces. So from a security standpoint, we are standing lockstep – Canada and the United States together – with Ukraine.

On the issue of security in the east, let me tell you where we are on this. First of all, it is clear to us – clear to the United States – that the essential first step for the implementation of the Minsk agreements is the establishment of security. Nobody expects that there are going to be elections, or that there is going to be progress in the Rada on implementing the obligations that Ukraine has under the Minsk agreements as long as Ukrainian soldiers are being killed and injured every single day out on the contact line. So our focus first and foremost right now is on establishing a real ceasefire, and then working toward the other Minsk benchmarks, including ultimately restoration of Ukrainian control over the internationally recognized border.

It is my expectation, and we’re still working on this with our other international partners, that if there is going to be an election, and we hope very much – as President Poroshenko hopes – that there will be a real, OSCE-standard election in Donbas to select legitimate Ukrainian authorities in those regions, that you will have to have some kind of presence, an international presence, to stabilize the security situation, to provide security for elections. But that’s about as far as we’ve gotten right now. We see the requirement. It’s going to have to be something that Ukraine requests, and that we develop in consultation with our European and other international partners. But again, the first step in this process is for Russia to do what it promised to do as part of the Minsk agreements, which is to stop sending troops and tanks and rockets across the border, to release all the hostages, including most importantly this week Nadiya Savchenko, to see a real ceasefire – to direct the separatists that it controls to implement a real ceasefire – and not to continue escalating the situation, which is what we have seen over the past few weeks with GRAD missiles and other heavy weapons being used again. And then to move toward these elections, which we hope will provide a way out of this terrible and terribly unnecessary war that has taken so many lives in the east and has done so much damage for no discernible reason.

MODERATOR: Mr. Ambassador, when you said that there was a visit by Prime Minister Trudeau to the White House, it took me at least two seconds to realize that you were speaking of this Prime Minister Trudeau.

AMBASSADOR PYATT: You’re dating yourself, like me, Andriy.

MODERATOR: So, the question is, how often and in which cases do you get feelings of déjà vu when you watch the Ukrainian situation.

AMBASSADOR PYATT: It’s a good question. There’s a lot that’s new here, and I’ll say right off I think it’s a mistake to say “this is just like the Orange Revolution.” Many of you lived through this, and you’re in a better position. Most importantly, the changes that Ukraine has gone through over the past two years are about a fundamental reorientation of the society, and they have come from the grassroots. I don’t think it’s any great secret, I remember one time in the early days of the Maidan, I was meeting with Serhiy Lyovochkin, Yanukovych’s chief of staff, and I said to him, “Serhiy, do you know what’s going on out there?” And he said, “Yeah, I’ve been down, I’ve seen.” I said, “Well what do you think?” He said, “I think it’s a lot bigger than the Orange Revolution.”

Again, I don’t think that’s well understood for somebody from outside of Ukraine, but for somebody who was here during that historic period, you had the sense that this was not about just changing personalities at the top. And in fact the politicians, it was very clear to me at the time, were trying to catch up with what was happening at the civil society level, what was coming from the grassroots. I think where one does get a sense of déjà vu, and it was alluded to in the early question, was the sort of relentless effort by these oligarchic clans to preserve their privilege, to claw back their influence. Yanukovych’s mistake, I believe – there were lots of them – but one of his big mistakes, it seems to me, was he was so greedy that he alienated himself from all of these other oligarchic groups, all of whom eventually abandoned him because he had so concentrated power.

In the aftermath of that, in the immediate aftermath of the revolution, the most hopeful thing that grew up were all of these civil society organizations, the people who came into politics from civil society – the new entrance to the cabinet. It’s like, in the American west, where I grew up, there’s a natural cycle in our high mountains where you have forest fires. A forest fire comes through, the pine trees burn but the tops of the trees are preserved, and that’s part of the natural cycle of renewing the forest. Ukraine in 2014 felt a lot like that. There were all of these new green shoots that were growing up in society in the aftermath of Yanukovych leaving the country.

I think the challenge now is that those oligarchic groups are clawing their way back in. And I really do believe that a big part of the story in Ukraine today is the battle between these two different Ukraines. The new Ukraine – the Maidan Ukraine – of rule of law, of European values, and other groups which are clearly still influential in this society that are not particularly concerned about the vast majority of Ukrainians, and are still trying to use politics for their own profit and enrichment.

Ukraine is not unique in suffering through this problem. Look at the United States. We had our robber barons. We had our oligarchs in the early 20th Century, and it took a very long time to work through laws, anti-trust, and regulatory oversight to bring those forces under control. And I think, again, that is part of the challenge for the Rada now, is how to build those rules. That’s why some of these votes that have taken place in the Rada on things like privatization and corporate governance are so incredibly important, because it’s about reorganizing the economy so that it cannot be so easily exploited by these oligarchic groups, who I would argue have done so much to hold Ukraine back from its full potential.

And I will say one last point on this. I mentioned earlier that one of the great privileges of my job is that I get to travel a lot in this country. Another part of being American Ambassador is you get to talk to a lot of these oligarchs. And while there are some exceptions, and I won’t name them here, most of these guys – and they’re all guys, for the record – most of these guys recognize that the model that they followed for the first 20 years or so of Ukraine’s independence has exhausted itself. That Rinat Akhmetov can’t get any bigger by buying former Soviet assets. That the only way these oligarchs prosper over the long-term is first of all if Ukraine prospers and grows at its full potential, which shouldn’t be capped at just 2% a year. This should be a super success story given the economic potential, given your price advantage, given your geography. You have a border with four EU member states. I remember traveling to Uzhhorod last summer. You’re three hours from Budapest. That has to be monetized. You have so much potential there. And again, whether it’s chemicals, metallurgy, agriculture, food, all of these are area that are ripe for additional investment and ripe for economic growth, but only if there is a level playing field, only if foreign investors know that if they come to Ukraine they’re not going to be ripped off in court, they’re not going to be challenged by somebody who’s connected to one oligarchic group or another.

So again, I come back to the enormous burden on the shoulders of everybody in the Rada today. You are the architects of a new Ukraine. I am absolutely convinced that Ukraine will never have a better opportunity to put itself on the path to sustainable, European growth. This is your moment.

MODERATOR: Another question from the audience? Yes please.

QUESTION: (Inaudible) My question is, what do you see as long-term priorities in the culture of education cooperation between the two countries, helping also Ukrainians to overcome post-Soviet ways of thinking, and thinking that all of the changes our country will become possible if the people change freely? And thank you for the help with the English language as well (inaudible).

AMBASSADOR PYATT: Great, well thank you first of all for the kind remarks. I’m very proud of our partnership with the team at GoGlobal and Ukraine Speaking. We are working with our Embassy public affairs team. I’m also delighted that we continue to grow our Peace Corps presence in Ukraine, and Peace Corps will continue to have a major role on these issues of English-language training as well. Minister Kvit will remember when I was here three years ago, a major focus of my speech was Ukraine in the global economy. And I said that one of the things I had sensed in my first weeks on the job was that the Ukrainian political debate was too inward looking and it wasn’t enough connected globally. And it’s a challenge that the United States faces as well, because we’re both big countries, so we spend a lot of time dealing with our internal stuff.

I think that point about recognizing where Ukraine fits into the global scenario is as important today as it’s ever been. It was interesting to me – we were delighted to see this visit that a delegation of Rada members made to Brussels last week. One of the faction heads who was there, I sat down and talked with him when he got back. I said, “What was it like?” And he said, “You know, Ambassador, it’s really striking to me how small Ukraine feels when you’re sitting in Brussels and seeing everything else that’s going on in the world.” And I think it’s an important lesson, and it cuts two ways.

On the one hand, Ukraine has never gotten as much international attention and as much international support as it has gotten over the past two years. Everybody realizes what you have gone through, as a result both of the inspiring stories of the Maidan – look at all of the attention in the United States to movies like Winter on Fire – but also the extraordinary experience of being invaded and Russia trying to tear your country apart.

So that’s the good. The bad is there’s a lot of other stuff going on in the world right now. From Syria, to refugees, to questions about Asian stability, so it’s really important for Ukraine, and for Ukraine’s political leaders, to demonstrate that they continue to move forward, that this country is making progress. Because, speaking now especially for the United States, to the extent Ukraine continues to move forward, I have no doubt at all about the commitment that the next President of the United States will have, whoever she or he is, to sustain the commitment that President Obama has made. But on the other hand, if the politicians, the leaders, allow continued political chaos, it will be much, much harder to make the case for continued support. That’s just the hard reality.

I applaud what you’re doing in the English language department. Building that sort of global – English as a tool of global connectivity – is incredibly important. And I think also, as the GoGlobal team regularly points out, the long-term goal isn’t just English, but all European languages, helping to build Ukraine’s ties to Europe so that, as I said, this revolutionary change you’ve been through over the past two years is truly irreversible.

MODERATOR: Before I pass the word to Vitaliy, you’ve named the good, the bad, what’s the ugly? Can we do it? Can we do away with it? (inaudible)

AMBASSADOR PYATT: The ugly is the corruption. There is no bigger challenge to Ukraine’s long-term success in my mind than continued tolerance for corruption. The Rada has done a good job in building new institutions. We are committed supporting the NABU, the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor. We hope very much there will be a new Prosecutor General chosen who enjoys the credibility and support of the Rada, from Ukrainian civil society. But this has to be rooted out. I think it does so much damage, first of all to your economic potential, it holds you back, it holds back the whole country, but it also drains confidence in institutions, in government, if people believe that corruption is the way you get by, the way you get ahead.

I recognize this has very deep roots. It can’t be changed from one day to the next. I think one of the areas where Kyiv-Mohyla has distinguished itself is in trying to root out the problem of corruption in universities, in education. From the stories I hear, it doesn’t start in universities. My wife is a teacher here and she has a lot of teaching colleagues who have young children who are in Ukrainian schools, and all of you who are parents have the same stories – the kind of petty corruption which drains confidence in institutions. That is by far the number one challenge, or as you put it, Andriy, it’s the biggest ugly.

MODERATOR: And from my own experience, I can tell you that even those of us who are grandparents do meet this problem.

QUESTION: Would you see a possibility to change the format of the Minsk agreement to any other one where there is much more influence and involvement of the USA?

AMBASSADOR PYATT: The simple answer to that for now is no. We’re going to stick to the Minsk format, to the Normandy format. We’re about supporting our Normandy partners. We are very deeply integrated into this process. Foreign Minister Steinmeier was in Washington two weeks ago, before the last meeting in Paris. The day after the Paris meeting of foreign ministers, our Deputy Secretary of State was in Paris meeting with National Security Advisor Ayrault and with the Foreign Minister. We’re doing as much as we can to support our European allies. I don’t see any prospect for now of trying to change that. Where I do see a particular role for the United States is in helping to support Ukraine – support Ukraine in a security sense, where we have a particular advantage. There is nobody better than the United States military in helping to build the capacity of our international partners, exercising leadership in NATO, and helping Ukraine and Ukrainian institutions move toward NATO standards. President Poroshenko has said he wants to move Ukraine toward NATO standards. That is going to require quite a bit of work in terms of changing security institutions to get away from these Soviet structures, move toward NATO standards of command and control, of leadership. I’m very glad that we’ve had a great partnership with the Rada in this regard. The work that our Marshall Center, the NATO training school in Germany, has done with the Rada to help build capacity for parliamentary oversight, civilian oversight of the military, which is something that does not come out of the Soviet tradition, but is very important to building a NATO-standard institution, so we’re committed to helping.

QUESTION: (Inaudible) My question is, you mentioned about institutions we are now creating – NABU, Anti-Corruption Prosecutor Office and so on – but what in your opinion is the key problem – in the institutions which we are creating, or as some of the current politicians say, the absence of political will, of political capacity in fighting this corruption?

AMBASSADOR PYATT: First of all, Yulia, thank you. Terrific question. And let me congratulate you and the whole team at the Ministry of the Economy, because I think the team that Minister Abromavicius put together at the Ministry of Economy demonstrated that it really is possible to make progress, that you can actually attack these mafias. And that, of course, is exactly why he faced the kind of criticism and obstacles that he did. And when I say part of the challenge is don’t give up, that’s aimed at you and all of your colleagues at the Ministry to keep doing what you’ve been doing. There’s a reason why the international community pushed so hard to have responsibility for Naftogaz oversight moved to the Ministry of Economy, and it was a vote of confidence in Minister Abromavicius, and most importantly the team.

Because ultimately, one of the things that I’ve learned as a manager, as a leader, is if you don’t build a team, nothing lasts. And that’s part of what the challenge is. I think that’s also my answer to your question about “what’s the problem, is it institutions or is it political will?” I really do believe that if you build the right institutions, the rest will come along. It takes political will to make those institutions happen, but Ukraine has enough strong human capital, it has a free media, including scrappy, independent media outlets like Hromadske and big oligarchic-controlled media. It has some of the strongest civil society organizations anywhere in Europe today. So I think if you get the institutions right, the rest will come along. And that’s where the United States and I know our European partners are committed to working with you.

And I think one of the things – again, I think back on my speech three years ago. At that point, the Association Agreement was all hypothetical. Now, it’s like a GPS. It tells you where you need to go. It provides a very clear set of obligations in terms of changes to regulations, to laws, and it’s a roadmap to a course that many of your eastern European neighbors have also followed with great success. So this is not a matter of being lost in the desert and having to figure out where do you go, you just have to follow the map. And that’s a choice that the Ukrainian people clearly have made.

MODERATOR: As we near the end of the time that we have, please be very concise, because I want to ask one final question. Go ahead.

QUESTION: My question is the next, it’s very painful question for most of Ukrainians – the language issue. As you know, on the one hand, we have a rapidly decreasing number of Ukrainian-speaking citizens, and on the other hand we have Russian troops that came to Ukraine to protect Russian-speaking Ukrainians. Be sincere – does it really matter for United States from your point of view on which language Ukrainians speak?

AMBASSADOR PYATT: No, is the short answer. I think if you look – look, again – I’ll talk about Prime Minister Trudeau. If you look at his press conference with President Obama, he switched seamlessly between French and English. This is a choice for Ukrainians to make, and we will respect whatever that choice is, but I think one of the brilliant aspects of Ukrainian culture, in my mind, has been your success at building an identity which is not uniquely rooted in ethnicity or language, it synthesizes all of the strands of Ukrainian culture.

I think it’s fantastic that your nominee for Eurovision this year is a Crimean Tatar. Jamala is both a symbol of Crimean resilience, but also, her mother tongue is Tatar. So, you know, finding a way to celebrate that identity in a manner that is inclusive, rather than exclusive, will make Ukraine stronger over time.

Every country goes through their own experience with this, including my own, which is the ultimate melting pot country. And what I would emphasize is these are choices that you as Ukrainians ultimately have to make.

MODERATOR: Sometimes we do not see paradoxes in very simple things. When Professor (inaudible) thanked the United States for their help in learning the English language, I thought that Ukraine in many cases may help learn Russian language to some people who want so much to allegedly protect our Russian-language compatriots. And of course there is an issue of creating the institute – of putting to norm the variety of Russian that is being spoken in Ukraine, but that is just an aside. My final question to you, Mr. Ambassador, is, you know, there were several flashbacks in my memory as you spoke. One we identified was the Prime Minister Trudeau of those times. Again, when you in the very beginning said that “I’ve seen Dnipro, I’ve seen the coast of Bessarabia and so on,” I remembered a song by my favorite British rock band, Slate, which is called “Far, Far Away.” And which says, “I’ve seen the yellow lights go down the Mississippi, I’ve seen the beauties of the world, and they are for real.” So my question for you – what is your feeling? To which extent Ukraine is for real?

AMBASSADOR PYATT: I think it’s very real. Let me go back to the language point I was making for just a second. I have so many memories from my time here, and I’ve been privileged to be in Ukraine during a truly historic period. But one of them that I will remember for a very long time was the extraordinary evening – the Okean Elzy 20th Anniversary concert at Olympiskiy in summer of 2014, so at the very peak of the war. What I remember about that was – and I don’t know if this was Slava, or who was responsible for it – but the opening band at that concert was from Kramatorsk. They were a Russian-speaking, scrappy rock-and-roll band from Kramatorsk. And I remember looking out at this enormous football stadium – 80,000 people – there must have been 75,000 vyshyvanka out of those 80,000. And I don’t think anybody cared about whether these guys were singing in Ukrainian, or Russian, or English, or whether they were from Kramatorsk, or, in Slava’s case, from Lviv. They were there because they were all different strands of Ukrainian culture.

And I think this is Vladimir Putin’s single most important error of judgment about this country. He famously has said, at one stage, Ukraine is not a real country. Ukraine is emphatically a real country. You have demonstrated that beyond any doubt, especially over the past two years. You have begun to build the elements of that identity, which are not just language, or clothing, or food, but are also rooted in political culture and this demand for a European standard of governance. And I remember talking to Minister Kvit once about the Revolution of Dignity. And I don’t know if you were the one who invented that phrase, but you were the first person I heard use that phrase. And I think that’s a very important aspect of understanding what Ukraine stands for today. Ukraine stands for dignity. It stands for the right of individuals to choose their own future. And those are principles which are both universal but also deeply, deeply resonant for us as Americans. And that’s why I’m confident, as I said earlier, that our support for Ukraine is something that is going to endure regardless of what happens in our elections, as long as Ukraine continues to march forward on the path of reform.

MODERATOR: Ladies and gentlemen, Geoffrey Pyatt, the Ambassador of the United States.