Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

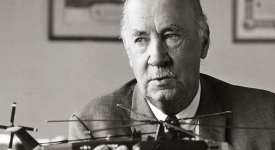

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Roosevelt establishes diplomatic relations with Soviet Union, Nov. 16, 1933

By ANDREW GLASS, Politico, Wash, D.C.

By ANDREW GLASS, Politico, Wash, D.C.

Fri, Nov 16, 2018

On this day in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ended nearly 16 years of frozen American relations with the Soviet Union. The breakthrough came after one-on-one negotiations in Washington between FDR and Maxim Litvinov (1876-1951), the Soviet commissar for foreign affairs.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, right, shakes hands with new U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, William Bullitt, on Nov. 17, 1933. Bullitt was appointed soon after Roosevelt had announced that diplomatic relations between the two countries had been restored. | AP Photo

Roosevelt in a letter to the Soviet foreign ministry, wrote: “I trust that the relations now established between our peoples may forever remain normal and friendly, and that our nations henceforth may cooperate for their mutual benefit and for the preservation of peace of the world.”

On Dec. 6, 1917, with the United States having entered World War I, President Woodrow Wilson broke off diplomatic relations with Russia, shortly after the Bolsheviks had seized power from the Tsarist regime after the “October Revolution.”

In the wake of the revolution, Wilson withheld recognition because the newly installed government refused to honor prior debts to the United States incurred by the overthrown Tsarist government, ignored pre-existing treaty agreements with other nations, and seized American property.

It did not help matters, from Washington’s viewpoint, when the Bolsheviks concluded a separate peace with Germany in March 1918 that ended Russian involvement in World War I. Despite continuing commercial links between the United States and the Soviet Union throughout the 1920s, Wilson’s successors upheld his policy of nonrecognition.

Sign up for our must-read newsletter on what's driving the afternoon in Washington.

By signing up you agree to receive email newsletters or alerts from POLITICO. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Roosevelt hoped that recognition of the Soviet Union would serve U.S. strategic interests by limiting Japanese expansionism in the Far East. He furthermore believed that diplomatic recognition would serve American commercial interests, an issue that held high priority in an administration grappling with the growing impact of the Great Depression. The United States also found itself isolated as the sole major power that continued to withhold official diplomatic recognition from Moscow.

The president approached the Soviets in October 1933 through two personal intermediaries: Henry Morgenthau, then head of the Farm Credit Administration and acting secretary of the U.S. Treasury, and William Bullitt, a former diplomat who, as a special assistant to the secretary of state, informally served as one of Roosevelt’s chief foreign policy advisers.

The pair in turn approached Boris Skvirsky, the Soviets’ unofficial representative in Washington, with an unsigned letter from Roosevelt addressed to Mikhail Kalinin, the official head of state. It requested that Kalinin dispatch an emissary to Washington. In response, Litvinov arrived in November.

The president and the top Soviet diplomat soon cut a deal. In return for recognition, the Soviets pledged to participate in future talks to settle their outstanding financial debts. After another private meeting with Litvinov, Roosevelt also secured guarantees that the Kremlin would not aid the U.S. Communist Party and would grant religious and legal rights for U.S. citizens living in the Soviet Union.

Bullitt went to Moscow as the U.S. envoy. Litvinov, who spoke fluent English, returned to Washington as the Soviet ambassador from 1941 to 1943 and joined the elite Metropolitan Club.

SOURCE: OFFICE OF THE HISTORIAN, STATE.GOV