Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

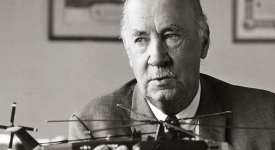

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

UKRAINE TRIP NOTES

Analysis & Commentary by Timothy Ash

Bluebay Asset Manage, London, UK

Wed, July 31, 2019

"I spent a few days in Kyiv this week, and obviously all the discussion was about what the new Zelensky administration will look like both in terms of personnel and policies."

Before moving on to a discussion of these, it’s perhaps useful to set the stage a bit, and herein I feel the urge to make the point that this year’s elections have the potential to be game changing for Ukraine. The operative word there is “potential”, and whether this “potential” will be realised is the $50 billion question - see below as to how I got to this figure.

But I think it is important to note that because of the elections and a number of other factors, Ukraine faces a situation where transformational change is really possible. And Zelensky herein has a unique opportunity to deliver really meaningful change to the electorate who voted for him. I really hope he - and his closest advisers (Andriy Bohdan, the head of the presidential administration, to be very specific) - realise this. Indeed, such an opportunity might not come around for a generation or more to come.

Why do I think this?

First, for the first time in Ukraine’s post independence history, the newly elected president has a majority in the Rada, with his party, Servant of the People, having secured 250-odd seats in the 420-odd seat Rada (excluding seats not allocated from the Donbas).

Second, the president was elected with a landslide victory with over 70% of votes cast in the second round presidential run off. And his popularity has remained around this level ever since.

Combining the first and second points, Zelensky has accumulated huge political capital to embark on much needed, and in some cases perhaps unpopular, reforms. Unlike Ukrainian leaders in the past, Zelensky cannot blame the Rada for not supporting reform. Zelensky controls the levels of power. The buck now absolutely and totally stops with him.

Third, the macro situation looks positive, and for the first time in many years, the Ukrainian leadership is not facing down an economic crisis. The economy is growing (~ 3% in real terms), inflation is in single digits and falling, the fiscal and current account deficits are modest/financeable (~ 2% of GDP), public debt is declining (~60% of GDP), the UAH is stable and the NBU is competent and accumulating FX reserves which are above the critical 3 months import cover threshold. The banking sector is stable - and no longer represents a large contingent liability on the state, unless the judiciary makes an error of epic proportions and decides to reverse the Privatbank nationalisation.

Fourth, Western donors appear supportive, with the IMF seemingly poised to transform the existing Standby arrangement into an augmented (in size and duration) extended financing facility - assuming agreement with the new government can be reached in terms of the broad direction of reform/structural benchmarks. I expect a deal by the time of the IMF AGM in October.

Fifth, over the past 4-5 years since Euromaydan, Ukraine has proven in a number of areas that it is absolutely capable of reform - e.g. NBU reform, banking sector, energy, and fiscal reforms. Through these reforms it has proven to have a solid, critical mass (even more) of very capable, clean, dynamic reformers, who have proven their ability to deliver in much more difficult circumstances.

Sixth, the reforms that Ukraine needs now to deliver are not rocket science - it’s not as though the country has seemingly intractable structural problems, such as say Lebanon, Libya, or Iraq, or maybe the UK with Brexit. It’s about improving the business environment, and key there is fighting corruption, improving the regulatory environment, reforming the judiciary, improving the tax and customs services and public administration in general, and also land reform and privatisation. Even better, many of these reforms have been started, but need completing.

The hope is that Zelensky and his close team of advisers understand all this and their importance in the historical context. The question they need to ask is are they personally able to deliver, and if not are they capable of choosing a team of capable technocrats who can step in and work with them to deliver.

One oft heard concern is that Zelensky, and his close team of advisers in the presidential administration, don’t trust the government structure, and want to run reform plans from the presidential administration. Under the current constitution Ukraine is a parliamentary/presidential democracy, and in theory the presidency is weak.

But in the region we have recently seen plenty of examples where presidents elected with strong popular mandates (Tadic, and then Vucic, in Serbia, and then Erdogan in Turkey, and perhaps even Putin in Russia with the job swap for a term with Medvedev) have exceeded their de jure constitutional limits, and de facto ruled their countries through strong use of presidential authority secured at the ballot box. We can argue over the relative success of those cases - Serbia (under Vucic, perhaps not Tadic) more successful perhaps than either Russia or Turkey.

A clear indication of Ukraine heading to a similar scenario would be Zelensky appointing a weak or inexperienced prime minister, who can perhaps easily be dominated by the presidential administration, led by a slick operator such as Andriy Bohdan. I guess no one would complain about de facto dominance of the presidency, if they delivered the required change.

And I guess then the question is does the presidential administration have the talent, the ideas and management skills to deliver change. Perhaps they do. Time will tell, but reviewing the above again, I cannot stress this enough, the leadership therein should recognise that this is a once in a generational chance for Ukraine. They should ask themselves are they really up to the task, or are there others more suited to the delivery of transformational change?

Now going back to the names that have seemingly been considered for the post of prime minister in Ukraine - Danylyuk, Abromavicius, Rashkovan, Vitrenko, and Kobolyev, I would even add in perhaps Lavrenchuk, and Goncharyuk, and I am sure there are others. But all of these are proven reformers, but it’s also possible to add the likes of Supryn, Nefyodov, Markarova. The point is that it’s relatively easy to appoint an A team of technocratic reformers who understand how the current system of governance works.

And if the Zelensky team decide to embark on a different path, centralising decision making in the presidential palace, and weakening the role of the cabinet ministers they should think long and hard about the opportunity which currently presents itself, the team of available technocratic reformers, and ask serious questions about their own capabilities and whether a presidential style system will prove more effective.

I have always thought the best managers are those that first recognise their own weaknesss, recognise and hire talent to fill their own gaps and then delegate and support their hires. Zelensky and his close team of advisers will succeed or fail on this very point. I wish Zelensky all the best in making this critical decision.

Beyond the discussion around personalities, it was encouraging this week to hear that one of the first and priority reforms that Zelensky and his team aim to roll out this autumn is land reform. It is still incredible in my mind that Ukraine, a potential agricultural powerhouse, and indeed once the breadbasket of Europe, has not rolled out land reform - which means allowing for a fully functioning market for land - years before.

It seems vested interests in big business, capturing various political leaders, have stalled this in the past. Having a functioning land market is so instrumental to kick starting credit and investment in the food and agricultural system. Sure some facilitating reforms need to be undertaken, such as improving the land cadastre. But again this is not rocket science.

And let’s think one step ahead, but also combining land reform with the Zelensky administration’s stated objective to accelerate the pace of privatisation. The state owns around 10 million hectares of agricultural land, out of the 40 million total. Let’s imagine it sells off these lands. Assuming a modest price tag of €5,000 per hectare, such land sales would yield €50 billlion in revenues for the state, or 40% of GDP. Let’s assume only 5% of the total is sold per year, that’s still the equivalent of 2% of GDP in annual below the line cash flows for the government.

This could fully cover the government’s budget financing needs, and would be transformational also in terms of public finances. Imagine the virtuous cycle of limited government financing needs, resulting in much lower borrowing costs, rating upgrades, which would filter through to the rest of the economy.

A lower interest burden for the government would free resources for other priority areas, such as social spending, defence and capital investment. It’s a win-win as land resources will be reallocated to those best able to use them, capital costs would be reduced, investment increased, fuelling accelerated GDP growth, job creation, and back to improved public finances.

And beyond the sale of state owns lands, a free market for land would also allow poorer rural inhabitants, perhaps not able to farm the land themselves, the ability to sell the land, or indeed, still to rent their land out, or even partake in equity release schemes. But it gives everyone more options. Net-net the agricultural sector in Ukraine remains the golden goose for the whole of society, it just needs ambition. And it seems the Zelensky administration have finally realised this. Let’s hope they deliver.

I left Ukraine feeling that something positive is afoot, and hence hopeful.