Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

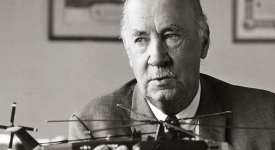

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

A Rocket Mogul Is Preparing to Launch a Union of U.S. and Soviet Technology

.png) Bloomberg Businessweek, Sep 22, 2020

Bloomberg Businessweek, Sep 22, 2020

Firefly Aerospace is seeking a niche below SpaceX’s jumbo rockets, while owner Max Polyakov faces some awkward questions.

PHOTOGRAPHER: KELSEY MCCLELLAN FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

This fish-out-of-water routine is fun, but Polyakov is someone the emerging commercial spaceflight industry needs to take seriously. To date, he’s put $150 million of his own money into rocketry, more than anyone besides Elon Musk, with SpaceX, and Jeff Bezos, with Blue Origin. Polyakov’s company, Firefly Aerospace Inc., runs a vast engine test site about a half-mile from the beer barn. From offices in nearby Cedar Park, Firefly executives have put the company in the mix for a series of contracts to launch satellites into orbit for NASA, the U.S. Department of Defense, and a string of commercial satellite companies.

In a move that would have been unthinkable in Polyakov’s formative years, during the twilight of the Cold War, he’s shifted some of Firefly’s engineering research and development to Ukraine, once the heart of the Soviet Union’s rocket program. This two-step is a big part of his pitch for Firefly—marrying the best of the former Eastern Bloc’s aerospace space talent with the latest American intellectual property, which he promises will be duly protected from foreign interests. (Polyakov spends most of his time in Silicon Valley.) The company’s 300-employee staff is working to launch Alpha, its first rocket, into low Earth orbit later this year from a pad at Vandenberg Air Force Base in Southern California.

At 95 feet tall with a cargo capacity of roughly 2,000 pounds, Alpha is aimed at an untapped niche of the spaceflight business. New Zealand’s Rocket Lab has corralled most of the contracts for small launches of 650 pounds or less with research bodies and satellite startups, while SpaceX and Blue Origin typically compete against government programs to carry jumbo payloads of 18,000 pounds or more. If it works, Firefly’s rocket could be an ideal middle option for satellite makers of all sizes, the equivalent of a minivan for clients that wouldn’t be as well served by either a sedan or a big honking bus. Firefly also has plans for a bigger rocket called Beta, as well as for its own satellites, propulsion systems, a reusable spaceplane, and a lunar lander.

First, though, Firefly will have to prove that its rockets can work—Alpha’s maiden voyage, most recently slated for early September, has slipped to November or December—and resolve some lingering questions about its owner. Ukraine may be an ally of the U.S., but the country remains rife with organized crime and whispers of espionage. Even some of Firefly’s own staffers have voiced concerns about how far they can trust Polyakov’s promises to protect American IP. Not helping matters is the provenance of Polyakov’s wealth. His ventures over the years have included dating sites long dogged by allegations of scamminess, another reason to be skeptical when contracting his space company to build what is essentially a missile.

.jpg)

Polyakov dismisses these nested national-security concerns as xenophobia, a barrier to entry thrown up by rocketry competitors. “Your passion can drive you forward wherever you were born,” he says. In three to five years, “we will be at the right time, at the right place, with a product that eats the market.”

As someone who’s spent about a decade covering the rocket industry, I’ve heard a lot of rivals and space officials slag off Polyakov as a dodgy foreigner with no real chance in the new space race, but the insinuations about espionage have yet to rise above the level of innuendo. So far, the sniping sounds pretty similar to the early criticism leveled at Musk, a figure the old-school space industry viewed with deep suspicion for years. Like Musk, who flew American astronauts to the International Space Station this summer, Polyakov appears to be a space nerd willing to wager his fortune that he’s figured out something other people have missed. Unlike Musk, he has yet to show he can build a viable business in orbit.

It’s unclear exactly how much money Polyakov has. He refuses to say, and there are no reliable estimates to draw on, though the combined value of the businesses he either runs or has invested in tops $1 billion. He’s slightly above average in height and build, but extraordinary when it comes to conversational energy. His mouth can’t quite keep up with the flurry of activity taking place in his brain, and the accented words shoot out in a jet stream of business-speak like “eat the market”—sometimes ambitious, sometimes joyful, sometimes hyperbolic. It took me a couple meetings and clinical study of some transcripts to reach a working proficiency in Polyakovese and to figure out what it means when he says, for example, that his businesses are in “full attack.”

After spending most of his 20s as a student, Polyakov created a string of successful gaming, dating, and advertising websites, along with a software outsourcing company and a series of business software makers. Some of these ventures went public, such as dating service Cupid plc. Others have been acquired by the likes of Oracle and Blackstone in deals worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Polyakov says the businesses he presently has a hand in employ more than 4,000 people in Ukraine, plus an additional 450 overseas.

The dating sites, in particular, don’t look great. During the 15 years from Cupid to the present, customers and outside investigators have repeatedly said that the sites Polyakov created lure paid subscribers with phony profiles of attractive users that hover just behind a paywall, then make it very, very difficult to cancel those auto-renewing paid memberships, which can run $25 a month. Some of the sites could be considered tasteful for the genre; others, such as Shag Together, less so. “All of my businesses and investments operate within the law and, where applicable, disclose their terms of use,” Polyakov says. “My focus is on space.”

Firefly isn’t among the businesses Polyakov founded, but by the time he took over, the spaceflight company, then called Firefly Space Systems, had its own problems. Chief Executive Officer Tom Markusic managed to secure the first of Firefly’s NASA and Pentagon contracts just a year after its 2014 founding, having run successful tests of its engines in Texas. By that time, though, Virgin Galactic had sued the company, accusing Markusic of stealing propulsion technology and other key intellectual property. (Markusic previously worked at Virgin, as well as at SpaceX, Blue Origin, and NASA.) By April 2017, a protracted legal battle and the Brexit-related departure of a key investor drove Firefly into bankruptcy, after the company had burned through $30 million.

Markusic, a religious man who believes he was put on Earth by divine providence to help humanity expand throughout the universe, prayed. Shortly thereafter, Polyakov acquired Firefly’s assets at auction for a few million dollars and rehired some employees, including Markusic, whom he reinstalled as CEO. (Firefly eventually settled the lawsuit with Virgin for undisclosed terms.) “I think it was practically a friggin’ miracle,” Markusic says.

In 2018, the year after Polyakov bought Firefly, I went with him to Dnipro, the heart of the company’s Ukrainian operation. Home to about a million people, the city sits in the central-eastern part of Ukraine and rests against the Dnieper River. Dnipro has its charms: peaceful parks, weekend markets, resorts near the water. The overall vibe, though, is undeniably Soviet. The facades of boxy buildings put up decades ago have started to crumble, and many of the public spaces suffer from similar neglect.

The Soviet Union began to turn Dnipro into one of its industrial crown jewels in the early 1950s. A former car plant was retooled into a maker of intercontinental ballistic missiles and then also passenger and cargo rockets. At the local space museum, in its dark, cavernous, cobwebbed glory, a nice older man says that by the end of the ’50s, the factory was making hundreds of ICBMs a year, the fastest rate of production in the world. He also notes Dnipro’s success at making satellites and rockets, including the Zenit, which industry types that include Elon Musk consider one of the best ever made because of its incredible engineering and