Featured Galleries CLICK HERE to View the Video Presentation of the Opening of the "Holodomor Through the Eyes of Ukrainian Artists" Exhibition in Wash, D.C. Nov-Dec 2021

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

"HOLODOMOR 1932-33: THROUGH THE EYES OF UKRAINIAN ARTISTS" - COLLECTION OF POSTERS AND PAINTINGS

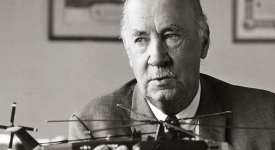

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

USUBC COLLECTION OF HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS ABOUT LIFE AND CAREER OF IGOR SIKORSKY PHOTOGRAPHS - INVENTOR OF THE HELICOPTER

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

Ten USUBC Historic Full Page Ads in the Kyiv Post

U.S. Ambassador Pyatt’s Interview with VOA's Myroslava Gongadze

Press office of the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv

Press office of the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv

Sun, Nov, 13, 2015

MS. GONGADZE: So thank you, Mr. Pyatt, for agreeing to this interview. I want to go a little bit back into the history when you were appointed and when you came to Ukraine in 2013.

AMBASSADOR PYATT: And you remember what you told me at the time?

GONGADZE: What did I tell you?

PYATT: You said don’t ignore the issue of press freedom in Ukraine.

GONGADZE: That’s good. That’s good. You don’t.

PYATT: It was good advice.

GONGADZE: But still, when you came, you were probably not expecting big turmoil. But you came, and it did. What was your feeling when you came to the country?

PYATT: Well, I don’t think anybody could have imagined the changes and the drama that Ukraine has been through over the past two years. The 21st of November will be the second year anniversary of the beginning of all of this. I think there were periods of enormous sadness, but also inspiring courage. Ultimately it’s about the Ukrainian people. I think back on the Maidan. I will remember the first time I heard, before it was public, that Yanukovych was not going to sign the Association Agreement. And I remember a conversation at that point with Sergei Lavochkin. And I asked Sergei, I said, how are you going to explain this to the people of Ukraine? What’s the diplomacy plan? He said, “I don’t know.” And I think ultimately, that’s the story of the Maidan. It was about Yanukovych trying to deny the choice that the Ukrainian people had made to move toward European institutions and European values.

GONGADZE: Was it exactly Yanukovych or maybe it was a bigger push from Russia?

PYATT: I don’t know. You have to ask Viktor Yanukovych that question. He’s the only one who knows. I know there were a lot of people around the Presidential Administration in those days who were just as surprised as we were by the decision that Yanukovych made. I will tell you, in my initial conversations with President Yanukovych after I arrived in August, he was all talking about the intention to take Ukraine towards Europe, toward European values.

GONGADZE: So four months, and…

PYATT: I think that’s what was the spark for the Maidan. Everybody in this country. 46 million people thought, “we’re going to Europe,” and then all of the sudden, in late November, he announces, “Change of plans — we’re actually going to the Eurasian Customs Union. I’ve changed my mind, I’ve had a conversation with Vladimir Putin,” but ultimately, what was going on in his mind, I think only Viktor Yanukovych will know.

GONGADZE: So what did you tell Washington back then, when the first people came on Maidan, when you realized that this is serious?

PYATT: Well it was very clear it was big. And I remember people around the government telling me, “this is bigger than the Orange Revolution — it’s much deeper.” And I remember walking around Kyiv those first days. I was out walking on St. Michael’s — on Mykhailivska — on the morning of, I guess it would have been November 30th, December 1st, right after this all started. This was a popular demonstration. I remember —it was so striking to me — the number of strollers that you saw, and people with young children, and people with their grandmothers. And these were people who were demanding a say in their country’s future.

The Maidan itself then went through this extraordinary 11 weeks. There were the events in the first week of December. Remember, that was during the OSCE Ministerial. All of Europe was here, all of these foreign ministers. But it was also the time when Yanukovych and Bankova chose first to send the Berkut against the demonstrators to try to clear Maidan, and all the violence there. And yet people came back. I remember that evening, I was woken up by a phone call. I won’t say who it was from, but let’s just say it is somebody who is now very prominent in the government.

GONGADZE: The Ukrainian government?

PYATT: In the Ukrainian government, who called me up to say, “Ambassador—they’ve sent the Berkut in. They’re trying to clear the Maidan.” And what I remember, from my house in Podil, I could hear the church bells ringing. You could hear the bells of St. Sophia and St. Michael’s were being rung. And as we watched this over the evening — this bizarre experience of watching it on the livestream, watching it on TV...

GONGADZE: And being there, basically…

PYATT: And sort of hearing what was going on. We were observers. But what was striking to me was the crowd was getting bigger. People were coming out. And I think that’s the essence of the courage that was demonstrated throughout the Maidan, and frankly, the courage that Ukrainians have demonstrated over this extraordinary 20 months. Vladimir Putin underestimated the Ukrainian people.

GONGADZE: Still, back in Washington, did Washington understand what was really going on? Did Europe understand really what was going on?

PYATT: We certainly understood how strong the demand was among the Ukrainian people to stay on the path to Europe. You remember, there was a very strong statement that Secretary of State Kerry issued that night in the first week of December when the Berkut were first sent onto the Maidan. He expressed — I think he used the word “disgust” — disgusted by what was happening, which is a strong word for a statement by the Secretary of State. But throughout this period, we were also very strong — I was coordinating very closely with Ambassador Tombiński, my EU counterpart; Ambassador Weil, my German counterpart — all of whom are close friends and are still here — but we were all saying the same thing: non-violence, work through Ukrainian constitutional structures, support democracy, support the values that you say you stand for.

GONGADZE: Then, again, war. It started and Russia would not give up, and it’s clearly not giving up even now. What was your expectation, and how was Ukrainian government ready to actually fight the war? Did you have a clear picture about Ukrainian readiness to really fight the war?

PYATT: Gosh, that’s a hard question. First, I will say what will stick with me was that first Sunday after Yanukovych fled. And one of my Ukrainian friends who’s now in the Rada, she said to me, “you know, that was our one weekend of happiness.”

GONGADZE: Before the war?

PYATT: Before the war, after Yanukovych had left. So it would have been the 22nd, 23rd. The morning of Sunday the 23rd. Remember, the Rada was in session, because they had voted with overwhelming support, including from Party of Regions representatives, to declare Yanukovych failing — that he had failed to discharge his responsibilities as President.

But what I will remember is, and this was totally unexpected for me, I went that Sunday morning to the Rada to go see Turchynov, who at that point was Speaker. And we were coming up Hrushevskoho — actually the back way, because the road was still not open from my house — and I was head-down, reading my Blackberry in the back of the car, and all of the sudden we stopped. And I looked out. And we were just by the hotel there, by the entrance to Mariinsky Park. We weren’t at the Rada yet. And I was thinking, “well, why are we stopping now?” And the whole street was full — and again, it was full of grandmothers, families, people with strollers, coming with flowers, coming with candles. And I realized they were reclaiming their democracy. They were coming to the Rada. And there was this sense of: “now we’re going to hold these people responsible, now we have to build a new country.” That was a profoundly inspiring period.

Prime Minister Yatsenyuk was named a few days later. He tells the story now, he arrived in office and he discovered that Ukraine had a few thousand dollars left in the treasury, the cupboard was bare. As he used to say — an army that couldn’t fight, an air force the wouldn’t fly, a navy that didn’t float. So Ukraine was at its weakest from a military standpoint. That’s when Putin moved into Crimea. I will always remember those first few days after the “little green men” showed up. People were trying to figure out, “what’s going on here?” Because it was so inconceivable that Putin would blow up international norms so dramatically, that he would violate the principle of territorial integrity that had been so important to preserving peace since the Second World War. It’s the most sacred principle of the Euro-Atlantic security community.

GONGADZE: So that’s why United States kind of pushed for a special international coalition to support Ukraine? When that decision to actually — that United States took the lead to help Ukraine?

PYATT: Well it was very clear, after we recognized that Putin had sent troops into Crimea, that the annexation was underway — even before the Kremlin ceremony where they announced all of this — it was clear that the United States was going to take the lead in terms of international sanctions. It was also very clear to us that Russia’s aggression would have to be met through non-military instruments, that our strongest levers were going to be economic pressure, and most importantly, the solidarity of the international community and with our European partners. And I think that’s an area where, again, Putin badly underestimated our ability to maintain unity with the EU and the other key players in the G7.

GONGADZE: There’s a lot of format of this international coalition discussion. Minsk, Normandy, Geneva. How those formats formed back then? And why United States kind of dropped out of the discussion between Russia, France, Germany?

PYATT: Yeah, I don’t think it’s fair to say we dropped out.

GONGADZE: Maybe not.

PYATT: And President Obama deserves enormous credit, I think, for the work that he has done — retail-level diplomacy with his European counterparts, lots of time on the phone with Chancellor Merkel, with Hollande, with Renzi, with all of our European partners, to make sure that the core principle was upheld. I can’t put it any better than President Obama did in his UN General Assembly speech a few weeks ago. We did not have a lot of immediate economic interests here in Ukraine, but the principles are very important to us, and the President, the White House, the Administration took a very strong position in response.

You know, a lot of the formats subsequent to that — I think people sometimes underestimate how accidental some of these diplomatic arrangements can be.

GONGADZE: That’s why I’m asking you.

PYATT: A lot depends on the calendar, on who’s meeting with who. Remember, we had the Geneva format for a while, which was Secretary Kerry and Lavrov, then you have the Normandy format. And remember, the Normandy meeting itself happened right after the first meeting between President Poroshenko and President Obama — even before Poroshenko was sworn in, President Obama met with him in Warsaw at the Solidarity anniversary. And that was a couple of days before Normandy, and of course, the President was very closely coordinating with Hollande and Merkel around all of that. So, not to overlook how much these formats depend on who happens to be seeing who on which day of the week. But the important thing — the United States has been deeply engaged since day one, and has played to our strength, which is our ability to mobilize an international coalition.

GONGADZE: Do you think that if United States would be in direct discussions at one of those format that Ukrainian position would be stronger?

PYATT: I don’t think so. I think we’ve found a good balance right now. And of course, we’ve had direct conversations with the Russians. Secretary Kerry with President Putin in Sochi back in the summer, the work that Assistant Secretary Nuland has done with Karasin. So it’s not like we’re not engaged on this, but we’re also of course coordinating closely with our European partners. And I think, most importantly, the work we’re doing to make Ukraine stronger. So I’m enormously proud of what we’re doing at Yavoriv and what we’ve done with security sector assistance. We’ve got our loan guarantees. We’ll have Secretary of Treasury Lew here tomorrow to continue our economic partnership.

GONGADZE: Did President Poroshenko ask you to participate in the discussion? What was his request?

PYATT: Both the President and the Prime Minister have been very clear in wanting American engagement, and they’ve gotten that. Remember, the Prime Minister — it would have been the middle of March — so just a couple of weeks after Yanukovych fled, when Prime Minister Yatsenyuk had his first meeting with President Obama in the Oval Office. President Poroshenko a couple of weeks after his inauguration flew to Washington for that extraordinary joint session of Congress. So we’ve been engaged here. I think the Ukrainian government wants to see the United States as closely engaged as possible. The most important principle for President Poroshenko is unity. We’re constantly saying to the Ukrainians we need unity among the democratic forces, unity between the Prime Minister and the President. President Poroshenko says back to us, “we need unity between the United States and Europe.” It’s a very important principle for Ukraine, because they realize that it’s part of Putin’s objective — it’s to split the West.

GONGADZE: I want to ask you one more question on the international side about Budapest Memorandum. Ukraine gave up nuclear weapons. All those rockets were turned to United States, it was a big danger for United States. Signed the agreement. Do you think international community and United States fulfilled that agreement?

PYATT: Russia is in flagrant violation of the obligation it undertook as a signatory of the Budapest Memorandum to respect Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. That’s clear. Through its invasion and annexation of Crimea and then its move into Donbas, Russia has done enormous damage to international security norms, and it has also damaged the principle of security assurances that were represented by the Budapest Memorandum.

That’s one of the reasons why the United States as worked so hard to support Ukraine, precisely because Ukraine had played this courageous role. All that being said, I don’t think nuclear weapons would have changed Ukraine’s situation, and in a lot of ways it would have made this crisis much more complicated.

I think, you mentioned that you had met earlier with Ukraine’s first president, and I think President Kravchuk — I’ve had some fascinating conversations with him about those weeks and the conversations he had with President Clinton, with then Deputy Secretary Talbott, Rose Gottemoeller, all of whom are people — in the case of Rose, who remain part of our Administration — deeply engaged on Ukraine issues. And they recognize the wisdom that Ukraine’s first independent leadership demonstrated in making that decision.

GONGADZE: Let’s now talk about what happened after Maidan and what we see right now in Ukrainian government. Not many people satisfied with the pace of reforms right now. How would you assess the reform agenda?

PYATT: This is a classic, “is the glass half full or half empty?” And I’m a glass half-full person. First of all, not to overlook all that Ukraine has accomplished. It’s had good elections, especially the election for President, the election for the new Rada, conducted under difficult circumstances, meeting the highest democratic standards.

Ukraine has made significant progress in a couple of key areas of reform. I’m a huge fan of Governor Hontereva and what the NBU, the Central Bank, has done to clean up the banking sector. About a third of Ukraine’s banks have been shut down because they were non-performing, significant moves against related party lending, giving Ukrainians and Ukrainian business confidence in the financial sector. Real progress in the energy sector, cutting out the middle men, getting out people like Firtash, creating a more transparent energy market, and most importantly, reducing Ukraine’s dependence on Russia as a gas supplier. You have defused the gas weapon that Russia has used for two decades to deny Ukraine’s strategic choices.

And then all of the incredible work that’s been done by Ukrainian civil society in the Rada to change the rules of the game. Whether financial disclosure, freedom of information, transparency of media ownership, public disclosure of property titles, all of these very technical steps that make it impossible to go back to Yanukovych-style governance in Ukraine. So these are all important steps. People want more. There’s no question in my mind what the single most important deficit of progress has been, and that’s in the area of anti-corruption. Building confidence in the courts, building confidence in the prosecutor’s office and in the legal system. There’s huge amounts of work to do there. And it’s not something that is going to be solved from one day to the next, but it’s an area where Ukrainians demand to see progress. I like the way Slava Vakarchuk put it in his comments in Washington earlier this week. He said, you know, Rome wasn’t build in a day, but Ukraine is making progress. And again, it’s precisely because Ukrainians are demanding higher standards that I’m confident the system is going to change.

One other point I would make, not to be overlooked. You’ve beaten Putin. When this whole crisis began, when the troops first came into Donbas in March and April of 2014, the Kremlin wanted most of Ukraine. It wanted Novorossiya. It wanted Odessa, it wanted Kharkiv. That’s never going to happen. What the Kremlin is left with right now — Russia and its proxies have this tiny little corner of Donbas. And you need to get that back, and we will work with you to get that back. But the rest of Ukraine has made its choice, and I don’t see it ever going back.

GONGADZE: You think these moves are irreversible? So Russia would not try to go forward and still manipulate the situation?

PYATT: I think Putin holds the switch. It’s very clear that the Kremlin has complete control over these military operations. That’s why the ceasefire — which remember, was signed in September 2014 — finally came into effect in September 2015, because the Kremlin made a decision to shift the focus, to busy itself in Syria. But the military force remains. You have a very large army, tens of thousands of soldiers trained and equipped by the Russian Federation, with more tanks and artillery and rockets and armor than many NATO countries. And it hasn’t gone anywhere. And that’s where the Minsk Agreement comes in.

GONGADZE: And they’re not fulfilling it?

PYATT: They are not fulfilling it. The only area of the Minsk agreement that has so far been implemented by Russia and its separatist proxies — and even that imperfectly — is the ceasefire. That took twelve months. And you see in the past week…

GONGADZE: There’s still fighting.

PYATT: There’s still fighting. And we’ve been very clear about that. And Chancellor Merkel has been very clear as well that the Minsk Agreement is not a smorgasbord that you can choose certain things from. It’s a set of obligations. Obligations that President Putin himself signed onto in February of 2015. And as Chancellor Merkel always reminds, the September 2014 obligations are part of the larger package. And that’s the standard that Russia needs to be held to.

GONGADZE: What is next for Ukraine? I mean, in the immediate future. What are you hoping for?

PYATT: You’re supposed to answer that question.

GONGADZE: No, no. You’re the Ambassador. I know my answer.

PYATT: This is for Ukrainians to decide. It really is. I think there’s a lot of hard work that lies ahead. Again, from an American standpoint, from the perspective of a sympathetic outside observer, the most important area that needs work now is the justice system — how to build confidence in the courts, in the prosecutor — in a way that the Ukrainian people themselves will respect. And I know that’s possible because we’ve seen what has happened with the Patrol Police, which is such a fantastic success and the Ukrainians are justifiably proud of that.

I was meeting today, actually, with Minister Avakov and the new head of the Patrol Police, Khatia. These are people who have a sense of vision, and they recognize that this is about changing the system, changing the patterns, and moving towards European standards. That’s what the United States is going to support, and I know that’s what our European partners are going to support. But ultimately, as I’ve said in some my speeches, you can’t just improve the police, you can’t just improve the national guard, you can’t just improve the army, you’ve also got to build the other pillar of rule of law, which is the courts and the justice system.

I am very encouraged by what’s been happening in the Rada with these constitutional reforms, and I think the President and his team at Bankova deserve great credit for the positive evaluation that they won from the Venice Commission, but the most encouraging thing for me is that there’s actually consensus. This is an issue that Ukrainian civil society, all of the members of the governing coalition, and I think even opposition bloc can get behind this principle of reforms for the judicial system. Because everybody knows, courts…

GONGADZE: It’s a fundamental building block.

PYATT: It’s a fundamental building block, and it’s what has caused so many deformities in Ukrainian politics in the past. As I’ve said before, this is the best chance Ukraine is ever going to have to build the kind of democratic, European future that the Ukrainian people deserve, and which Ukrainians thought they were going to get after Ukrainian independence but were thwarted from for two decades.

GONGADZE: Every single U.S. Ambassador who spent time in Ukraine became a big lobbyist for Ukraine in the end. What do you expect for yourself?

PYATT: Oh gosh. You know, Myroslava, I do my job one week at a time, and I have given no thought at all to the long-term future. It’s been a source of great encouragement and benefit to me that, as you say, all of my predecessors have remained engaged — many of them in Washington. I think that reflects, first of all, how compelling this country’s story is. Ukraine — if you look around the world, if you were going to give a prize to a country which got a raw deal out of the 20th Century, Ukraine is pretty high on that list. But now there’s a sense that they’re building something fundamentally different, and we want to support that. I think all of my predecessors — first of all, I met with every single one of them before I came out here — and none of them told me, none of them predicted what was going to happen, so that makes me feel a little better. But they’ve all said, as well, that this is a country which has such a compelling history, that has such a strong cultural identity, and which deserves much better than it’s gotten in the past.

GONGADZE: Thank you so much for your work, and Slava Ukraini.

PYATT: Slava Ukraini. Great to see you. Thank you, Myroslava.

###

NOTE: A video of the interview is available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NNH0ZRZeGGw