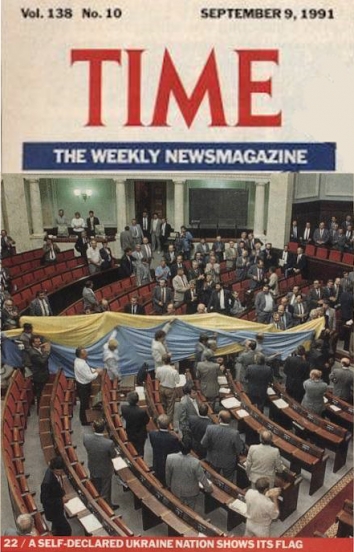

Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

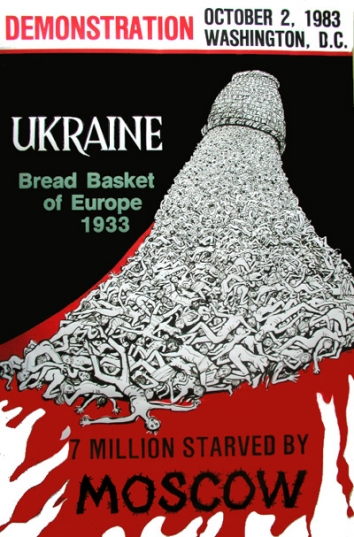

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

AMERICAN FAMILY PROVES THAT PERSISTENCE PAYS OFF

David and Daniel Sweere say the country's agricultural potential is staggering.

Mark Rachkevych, Kyiv Post, Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, June 3, 2011

DEMKY, CHERKASSY OBLAST – Twenty three births were recorded in this central Ukrainian village in 2007, Atlantic Farms’ second year of operations. It was 22 more births more than in 2005, when the American family-owned business became the hamlet's sole private sector employer.

The father-and-son tandem of David and Daniel Sweere keep 300 Demky residents busy farming 6,500 hectares and raising 3,000 head of beef cattle in a village whose aging population numbers less than 1,000. It’s all part of Kyiv-Atlantic, the Sweere family’s majority-owned – and still growing – agribusiness holding in Ukraine.

They cultivate an additional 3,000 hectares in southern Kyiv Oblast where they produce vegetable oil, multi-game feed, flour, pasta as well as other value-added products. They also run a chain of 150 country stores that sell basic farming tools, including feed, seed and fertilizer tailored for small producers. Ukrainian buyers make up roughly 72 percent of the company’s sales.

Much like post-Soviet Ukraine’s choppy development, the Sweeres have come a long way from farming Minnesota’s Red River Valley.

When Ukraine was on the verge of gaining independence, a then 45-year-old David Sweere (now 66) started operations in Ukraine after selling off his agribusiness in the United States. Although it accounted for only 3 percent of the Soviet Union’s territory, Ukraine was at the time feeding most Soviets and accounted for 25 percent of Soviet agriculture output.

But farming technology used in Ukraine was hugely inefficient, exploiting only a small amount of the rich “black soil” that carpets the country.

David Sweere smelled huge potential in Ukraine, home to some of the world’s richest farming land. As the nation’s economy collapsed and entered a painful transition to a market economy in the early 1990s, David Sweere and his wife Tamara started trading diesel fuel from Russia and the Black Sea and bartered directly with collective farms that didn’t have hard currency to fuel their machinery.

In past Kyiv Post interviews, David told of being hassled by the tax police and receiving death threats. But he never gave in. And his tenacity and farming know-how ultimately paid off big time in Ukraine.

“My father was lured by the amazing farming opportunity that Ukraine offered,” said 46-year old Daniel Sweere, who joined his father’s Ukrainian farming business in 1994.

David’s original and lofty plan for Kyiv-Atlantic was to help transform Ukraine into the only protein self-sufficient nation in Europe. Almost two decades later, Ukraine is just starting to inch towards attaining such agriculture highs.

The country still “has the potential of feeding itself by efficiently converting vegetable protein to quality milk, meat and eggs,” proclaimed David.

Given Ukraine’s rich soil and ideal farming climate and precipitation, David said Ukraine can become an efficient miracle by using modern seed genetics, carefully targeted plant and soil treatment and create a more robust market for value-added agricultural products like food.

The family built up their grain feed plant and elevators in the 1990s surviving the 1998 Russian financial crisis. “That was tough. We just started that business, had foreign debt and it took us five years to recover,” said David Sweere.

The process of breaking up Soviet-era collective farms was already underway. Currently 84 percent of arable land in Ukraine – roughly 29 million hectares – is privately owned by citizens with the average size of land plots being 3.7 hectares.

Much like the nation’s growing number of enormous agribusiness holdings who lease land from villagers, the Sweeres started farming in 2000.

By this time agricultural output in Ukraine had dropped almost 50 percent from their peak Soviet figures. An estimated 12-15 percent of arable land is today farmed by large, efficiency farms, BG Capital’s agriculture experts said.

For Ukraine to unleash its agriculture potential, government must ‘get out of the way and let the private sector take off.’

In 2002, Kyiv-Atlantic finally made a profit again. It received a cash infusion from Danish investors in 2006 and progressed up to the 2008 global financial meltdown. “We were ahead of the curve during the crisis. It didn’t hurt us that badly,” said David.

Employing 1,200 workers, the Sweeres have kept pumping money back into their business. They’ve invested more than $30 million into building a 40,000-ton grain elevator, a feed mill and an oil processing plant. The company's 2010 turnover was $36 million.

“It’s better to become better than bigger,” said David, adding that inconsistent government policies and overregulation is holding the nation’s agriculture sector back.

Still he said that because of the immense opportunities “you have to grind it out, really stay tenaciously involved, be vigilant and tough at times. You have to say to the tax inspector: ‘look, I’ll pay my taxes, but I’m not going to pay more.’”

His son Daniel said success also depends on an emphasis on efficiency, smart yet intensive use of inputs such as fertilizer and use of modern machinery, a practice that only large farms can apply.

David said that another impediment is the cost of financing. Although his company on the average doubles the amount of money it puts into each hectare, borrowing is expensive, often in the double digits since land can’t be used as collateral and banks haven’t devised specialized loans to match farming cycles.

But in order for Ukraine to unleash its agricultural potential, he said, government must “get out of the way…and let the private sector take off.”

Ukraine expects the harvest this year to amount to at least 43 million tons of grain. But experts say Ukraine could easily double or even triple that amount if investment is encouraged.

For the “when” part to happen government must take almost revolutionary measures to do genuine reform in the agricultural sector.

“Unfortunately, that takes political will and, of course…they perpetuate their self-interests rather than national interests which is not uncommon to Ukraine but unfortunate to the people,” said David Sweere, who has been in Ukraine long enough to see it all.

Still, the country's potential continues to be staggering for both father and son Sweere.

“It’s not a question of ‘if’ but a question of ‘when’,” David said of Ukraine’s chances of regaining its reputation as the “Breadbasket of Europe.”

LINK: http://www.kyivpost.com/news/business/bus_focus/detail/105914/

NOTE: Kyiv-Atlantic is a member of the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC), Washington, D.C., www.usubc.org.