Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

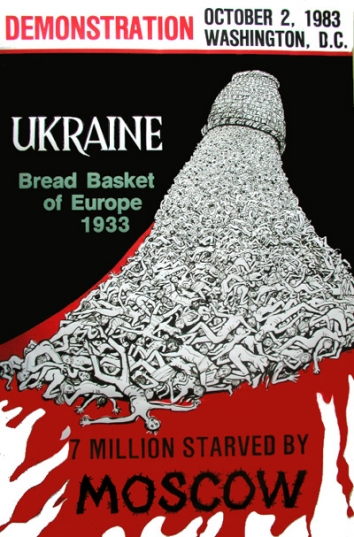

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

CHRISTIAN IMAGERY, WITH LOCAL CHARM AND VITALITY

Art Review: By Ken Johnson, The New York Times, New York, NY, Thu, July 1, 2010

CHRISTIAN IMAGERY, WITH LOCAL CHARM AND VITALITY

The Glory of Ukraine,” at the Museum of Biblical Art in New York City,

offers icons, paintings and embroidery from the 11th to the 19th centuries.

Art Review: By Ken Johnson, The New York Times, New York, NY, Thu, July 1, 2010

NEW YORK - In 1051 a Greek Orthodox monk named Anthony retreated to a cave overlooking the Dnieper River in Kiev. Disciples came, buildings were constructed, and, by the 17th and 18th centuries, the Monastery of the Caves embraced a flourishing metropolitan sprawl of 3 Ukrainian cities, 7 towns, 120 villages and more than half a million peasants.

Today, in addition to a multi-tiered, gold-domed bell tower soaring more than 300 feet, its most remarkable feature is a system of subterranean caves, including living quarters and chapels, and a labyrinth extending more than 650 yards into the Berestov Mount.

The monastery operated an art school from the 17th century to 1917 that attracted students from all over Eastern Europe and Russia. Now the National Kiev-Pechersk Historical and Cultural Preserve — as the monastery was renamed in 1926 under the atheistic Soviet government — boasts a collection of more than 70,000 pieces, among them icons, paintings, metalwork and embroidery.

A sample of the monastery’s holdings, along with selections from the Lviv National Museum, is on view in “The Glory of Ukraine: Sacred Images From the 11th to the 19th Centuries,” a captivating exhibition of works from Ukraine at the Museum of Biblical Art.

Ukrainian artists were not exactly up to speed as far as developments in Europe went. They mixed Western and Byzantine influences, but what they knew about German, French and Italian masters came mainly from engravings and copies, and their efforts, as evinced by this show, had none of the naturalism or technical polish of those role models. Compensating for lack of finish, though, is a naïve charm and graphic vitality.

A 16th-century icon representing the Transfiguration has Jesus hovering in the sky backed by a black starburst inside a frosty-blue circle, with Elijah and Moses in attendance. Below, on rocky ground defined by crisp, pleated forms that look as if they were cut by scissors, three apostles have fallen like dancers in rhyming postures. The painting is a marvel of linear and planar syncopation.

That no works are attributed to a known artist adds to the sense of a folk culture animated not by authoritarian dogma or academic formulas but by genuine religious feeling and beloved traditions. This is not the severe, punitive aspect of Christian imagery but a more benevolent, mystical side. More than a quarter of the paintings represent Mary, in one form or another, which may have something to do with the prevailing compassionate spirit.

In an 18th-century icon called “The Exaltation of the True Cross,” a bearded and crowned saint and a deacon, both in sumptuous gold-trimmed robes and standing on a circular dais, together hold a tall wooden cross, as other saints and congregants look on. It has the kind of hair-raising otherworldly atmosphere that you often find in the artworks of self-taught visionaries of different times and places.

The late-17th-century “Saint Nicholas, the Miracle Worker,” in which the beneficent saint in a gold-and-red robe seems gigantic against a background of hills and medieval buildings, has a similarly numinous feeling. His presence is enhanced by the brightly gilded, delicately carved floral pattern that substitutes for the sky.

Yet another striking icon, painted on a squarish, 15-inch panel in the late 18th or early 19th century, represents 118 golden-haloed saints arranged as if on bleachers for a class portrait, with an image of the main church of the Monastery of the Caves held up by angels in the center. The remains of all 118 beatified luminaries are said still to be contained below ground.

Despite its tragic subject matter, one of the most intriguing paintings is an 18th-century landscape of episodes from Jesus’ Passion acted out by doll-like figures within a circular stockade made of pointy wooden pickets. It looks as if it was based on a miniature tableau created for Easter by a model-making hobbyist. The rustic fence, notes a catalog entry, symbolizes “Paradise in Heaven”; the cross on which Jesus hangs in the center becomes the “Tree of Life.”

Paintings that try to imitate the drama and illusionistic space of the European Baroque are less interesting, but one, from the 1760s, is spectacular. On an arch-topped panel more than five and a half feet tall, the Archangel Michael and his angelic retinue, all in resplendent deep green, red and gold, stand symmetrically on a bed of clouds. Golden beams radiate from a small figure of Jesus in the sky, a dove flying above him and, at the very top, an all-seeing God with outstretched arms. It is a flamboyant trip.

Among objects on display — including gilded silver chalices and book bindings — are blessing crosses with finely engraved, gilded silver handles and frames containing images of Jesus and other luminaries relief-carved in eye-straining miniature in cypress wood. Made in the early 18th century, they are among the exhibition’s most virtuosic works.

For sheer beauty, there is a priest’s vestment called a phelonion. This one, made in 1756, is a delirious patchwork of satin, linen, chenille, silver thread, damask and embroidery stitched into sinuous, layered patterns of checks, ribbons, flower blossoms and fruit. The phelonion represents the robe that Jesus wore when he was tried by the Romans; this one’s unabashed aesthetic hedonism could not contrast more with the tragic abjection it is meant to symbolize.

“The Glory of Ukraine: Sacred Images From the 11th to the 19th Centuries” runs through Sept. 12 at the Museum of Biblical Art, 1865 Broadway, at 61st Street; [New York, NY] (212) 408-1500, www.mobia.org.

NOTE: A version of this review appeared in print on July 2, 2010, on page C23 of the New York edition of The New York Times.

LINK: www.nytimes.com/2010/07/02/arts/design/02biblical.html

USUBC FOOTNOTE: "The Glory of Ukraine" will be presented in two separate art and culture exhibitions – "Sacred Images from the 11th to the 19th Centuries" and "Golden Treasures and Lost Civilizations." One or both of the exhibitions will be shown in New York City, Washington, D.C., Minneapolis, Omaha and Houston in 2010 - 2012. The Foundation for International Arts & Education (FIAE), www.fiae.org, is presenting the two major Ukrainian exhibitions, in cooperation with the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC), www.usubc.org, and with support from the Embassy of Ukraine in the United States, http://www.mfa.gov.ua/usa/en.

"The Glory of Ukraine: Sacred Images from the 11th to the 19th Centuries" exhibition will be held the Meridian International Center, Washington, D.C., from October 2010 through January 2011. Corporate sponsors are needed for the exhibition at the Meridian International Center. For more details on the corporate sponsorship needs please contact Iryna Teluk, USUBC, e-mail: iteluk (at) usubc.org; and Elena Romanova, Foundation for International Arts & Education, e-mail: elenar (at) fiae.org.