Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

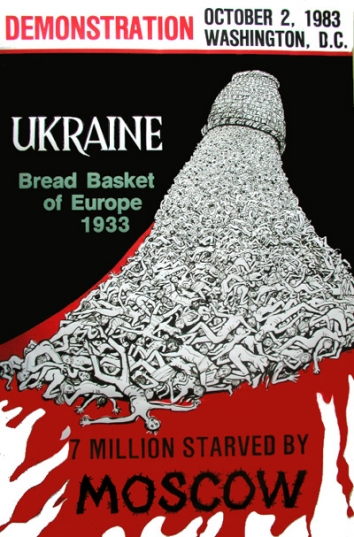

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

OVERVIEW OF UKRAINE'S LEGAL REGIME FOR UPSTREAM OIL & GAS SECTOR FOR 2011 AND BEGINNING OF 2012

By Dr. Irina Paliashvili, Managing Partner, RULG - Ukrainian Legal Group, P.A.

U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC)

Washington, D.C., Friday, February 24, 2012

LINK: Article Upstream Legal Regime (PDF)

KYIV — We have been reporting on the new developments in Ukraine’s upstream oil & gas sector for many years, and 2011 and the beginning of 2012 turned out to be one of the most eventful periods to date. It was signified by substantive legislative changes, both enacted and pending (with some of the legislative initiatives vetoed by the President), as well as by regulatory reform in the area of Subsoil use.

A number of cardinal changes have also occurred in the legal regime for production sharing agreements (“PSA”), and 2011 culminated in the adoption of two Cabinet of Ministers Resolutions on preparing PSA tenders for Yuzivska and Olesska Subsoil areas, with tender announcements expected by the end of February 2012.

All these developments were accompanied by frequent (and not always well-coordinated) statements by various senior government officials and active positioning of international oil companies (“IOCs”) and private-sector and State-owned national oil companies (“NOCs”) in anticipation of new projects, most notably in Shale gas and the Black Sea Shelf areas.

Despite the unusual outbreak of activity and reforms, investment opportunities in 2011 again failed to materialize. However, the sheer scope and depth of developments and the ongoing political and economic complications related to energy supplies, suggest that this time around the Ukrainian Government (“GOU”) is serious about opening up the upstream sector for international investors.

It is not clear, however, how and on what conditions IOCs would be allowed to participate in exploration and production activities in Ukraine. The existing legal instruments, such as joint activity agreements (“JAAs”) and joint companies (“JVs”), remain severely restricted and vulnerable to intervention by GOU and courts, and in practice no attractive Subsoil areas are offered to investors at auctions, if offered at all.

Moreover, the PSAs, which were strongly favored by IOCs as the most investor-friendly and stable instrument, underwent cardinal changes in favor of the State, and more changes are pending. The legal regime for upstream activities in Ukraine continues to be divided into more traditional Licensing Regime, with Subsoil Licenses (referred to in legislation as “special permits” to use Subsoil) generally offered at auctions, and the alternative PSA Regime under which the investor obtains the rights to use Subsoil under a production sharing agreement.

The legislation for the Licensing Regime remains confusing, conflicting, unstable and archaic. In fact Ukrainian laws and regulations, including in the area of Subsoil use, are drafted in such a complicated and legalistic language that for international investors it is sometimes very hard to understand the simplest provisions. We probably need a glossary of simplified terms, and in this article we sacrifice some accuracy in terminology for the sake of describing the current legal regime in comprehensible language.

It has been an old trick of GOU to camouflage the lack of political will by telling investors that yet another law or regulation needs to be enacted in order to make things happen. Experienced investors no longer accept this argument, finding the existing legal regime, with all its flaws, more or less adequate, and demanding real actions instead of yet another piece of legislation. And it seems that the GOU is finally doing both (although with the customary lack of transparency and clarity): amending the legislation and preparing real projects to be offered to investors.

The GOU’s key strategic goals also shaped up, while the details are still being worked out:

• favoring State-owned companies at the expense of private-sector companies, including reconfirming the advantages for State-owned companies (in which the State has a stake of as little as 25%) in obtaining Subsoil Licenses in a non-competitive and non-transparent procedure under Licensing Regime and imposing on investors a “Local Partner” (a fully or partially Stateowned company with a yet unidentified stake by the State) under PSA regime;

• finally allowing to transfer or pledge Subsoil Licenses, thus creating real market conditions for investment in exploration and production, but with significant caveats (the relevant bill is pending in Parliament);

• improving old and preparing new legal instruments for investors;

• increasing the fiscal pressure on the oil & gas industry

In short the GOU is in the process of replacing the old relatively liberal regime but no action, with a new less favorable regime which carries real opportunities. IOCs respond with numerous complains, but readiness to invest. To this end GOU announced that in 2011 Ukraine reached an agreement with 21 IOCs on exploration and production of hydrocarbons (most of them still on the level of MOUs or Joint Study Agreements, which are largely of declarative nature).

There were several reports on the Palace area on Black Sea Shelf to be developed jointly by Naftogaz and Russia’s Gazprom with the 50-50 split, on a basis of some “joint venture”. Negotiations also were reported between Naftogaz and Brasil’s Petrobras on development of Black Sea Shelf.

This outline of the current legal regime for upstream sector consists of the following sections:

I. Subsoil Licensing Regime

(A) Reform of the Regulatory Bodies

(B) New Licensing Regulations

(C) Pending legislative initiative on allowing transfer of rights to use Subsoil

II. Joint Companies (JVs) and Joint Activity Agreements (JAAs)

III. Production Sharing Agreements (“PSA”) Regime

(A) Changing the Rules of the Game

(B) Amendments to the PSA Law: stabilization clause restored; the PSA List removed

(C) Practical Opportunities for PSAs: GOU Resolutions on PSA tenders for Yuzivska and Olesska Subsoil areas

IV. Shale Gas: Legal Status Changed

I. Subsoil Licensing Regime

(A) Reform of the Regulatory Bodies

GOU has been known to regularly rename the government bodies without any substantive changes, in particular those in charge of regulating Subsoil use. The long standing key regulator (often referred to as “Authorized Body”) was the Ministry of Ecology with some secondary and technical functions assigned to the Geological Service, which for the past few years was integrated into the Ministry.

In 2011, however, a substantive reform occurred in regulatory bodies: the Geological Service was given a separate independent status, was renamed (again!) “State Service for Geology and Subsoil” (known by its Ukrainian abbreviation “Derzhgeonadra”) and became the key regulator: the Authorized Body in the area of Subsoil use and in charge of issuing Subsoil Licenses.

The Ministry of Ecology retained some secondary functions, including under the strange formula that the activity of the Derzhgeonadra is “directed and coordinated by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine through the Minister [not the Ministry, but the Minister!] of Ecology and Natural Resources”. The Ministry of Ecology quickly adopted a number of regulations highlighting its regulatory role, including the procedure for granting clearance by the Ministry for issuance of Subsoil Licenses by Derzhgeonadra, but the new reality is that Derzhgeonadra, and no longer the Ministry, is the key Authorized Body.

(B) New Licensing Regulations

The GOU adopted in 2011 the long-awaited measure on replacing the annual procedures for granting Subsoil Licenses and holding subsoil auctions (“Licensing Regulations”) with permanent Licensing Regulations. Of course even the latter can be amended, but in general the chaos of changing the rules of the Licensing Regulations every year has ended.

The new Licensing Regulations were adopted on 30 May 2011 by two GOU Resolutions: No. 615 "On Approving the Procedure for Granting Special Permits to Use Subsoil" ("Licensing Procedure”) and No. 594 "On Approving the Procedure for Holding Auctions for Sale of Special Permits to Use Subsoil" ("Auction Procedure”).

The new Licensing Regulations have a major significance for the upstream sector and deserve a separate detailed analysis, but in this article we highlight only the most important negative and positive trends.

NEGATIVE TRENDS:

• Despite declaring equal regime for national and foreign investors, including in the Program of Economic Reforms for 2010-2014, the GOU reaffirmed the unfair preferences for State-owned companies (in which the State has the stake of as little as 25%) allowing Subsoil Licenses to be granted to them without an auction or tender (i.e. on a non-compete and non-transparent basis).

• There is a confusion in the Licensing Procedure as to extension of various Subsoil Licenses, in particular it is not clear how many times the Production License or a single Exploration/Production License can be extended (the extension of Exploration License is expressly limited to two times).

• The procedure and specifics of issuing Subsoil Licenses for areas located on the Shelf was not clarified.

• Although the Licensing Regulations do not list the categories of Subsoil users, the reference is made to the respective Article 13 of the Subsoil Code, which expressly includes foreign (non-resident) legal entities and physical persons. At the same time, the list of documents that need to be submitted with the Subsoil License application (Annex 1 to the Licensing Procedure) makes it clear that foreign national cannot apply for a Subsoil License directly (i.e. outside of the auction procedure) because they cannot possess the required documents.

POSITIVE TRENDS:

• While the Licensing Regulations in previous years deprived the holders of Exploration Licenses from an opportunity to convert them into Production License without an auction, the current

Licensing Procedure allows a holder of Exploration Subsoil License, which conducted geological exploration and calculated and approved the reserves, to obtain Production Subsoil License without the need to compete for it at an auction.

• The single Exploration/Production License is now included in the Licensing Procedure, the term of which is 20 years on-shore and 30 years off-shore.

• The Licensing Procedure introduced an interesting new language with regards to reformulation and transfer of a Subsoil License. It divides such cases into (i) “reformulation”, which only includes technical grounds such as change of license-holders name, address, etc.; and (ii) “introducing amendments” to the Subsoil License, which allows actual transfer of Subsoil License in case the license-holder creates a new joint company where it owns at least 50% stake.

This latter transfer provision, however, contradicts the Subsoil Code and the Law “On Oil and Gas” and therefore its legality is questionable (the amendments are now pending to these Laws, which would allow transfer of Subsoil License and which are described in sub-Section (C) below).

• Article 6 of the Auction Procedures stipulates that the auction organizers must obtain all approvals and clearances with regards to the Subsoil areas offered at auctions.

In practice, as in previous years, the GOU offered negligible number of Subsoil License for hydrocarbons at auctions. In 2011 only one auction was held on 27 December and only one oil & gas area was included, the Exploration and Test Production License, which was purchased by a local private company Golden Derrick. At the same time, the GOU continued to grant Subsoil Licenses on a preferential basis to State-controlled companies under a non-competitive procedure, i.e. without an auction and continued to adopt decisions to this effect.

(C) Pending legislative initiative on allowing transfer of rights to use Subsoil

Subsoil Code (Article 16) and the Law “On Oil and Gas” (Article 14) contain an expressed flat ban on any alienation/transfer by the license-holder of the rights to use Subsoil (i.e. the Subsoil License), including expressed ban on contributing these rights to JAAs or JVs, and implied ban on pledging such rights.

This ban in effect deprives investor in a JAA and a JV (in case JV itself is not the license-holder) from any rights to the Subsoil License making these instruments unattractive to strategic investors, and deprives the license-holders from the possibility to seek outside financing because they cannot secure their obligations by pledging their rights. An attempt in the Licensing Regulations to stipulate limited possibility for licenseholder to transfer the Subsoil License to a JV (in which the license holder has at least 50% stake) is illegal and cannot be relied upon because it contradicts the above ban.

GOU understands that the ban is a serious obstacle for attracting investors and supports a new Bill pending at the Parliament that would lift the ban on alienation/transfer of the rights to use subsoil and allow mortgaging/pledging of such rights under certain conditions.

Without going into detail on various conceptual and drafting shortcomings of the Bill, one of its key problems is that the license-holder will be obliged to offer the rights first to the State, and a 100% State-owned company (presumably an oil & gas company, which would be a direct competitor to the investor who originally intended to acquire the rights) would have a preemptive right to acquire them.

In short, the initiative to lift the ban is long overdue and absolutely necessary to create market conditions for investment in exploration and production

of natural resources, but the Bill does not meet this goal and needs to be substantially improved to achieve it.

II. Joint Companies (JVs) and Joint Activity Agreements (JAAs)

Any partnership with the license-holder, which is a State-controlled company (in which the State has a majority stake), either a JAA or a JV, is subject to a number of special restrictions and requirements, including inter alia:

(A) For JVs:

Specific GOU and various other approvals must be obtained for forming a JV with a Statecontrolled company, and in case the JV is formed outside Ukraine, an individual license of the National Bank of Ukraine will be also required. In addition a provision exists in Article 11.7 of the Law on Management of State Property that in any company newly created on the basis of objects of State property, the corporate rights of the State must exceed 50% of the authorized fund.

This provision, although not entirely clear, has been generally interpreted to mean that the State-controlled company must have a stake in the JV exceeding 50%. Some legal experts take a position that this requirement can be avoided by the State-controlled company making a contribution to the JV, which would not qualify as “objects of State property”, but in addition to ambiguous legality, the question would arise what exactly the State-controlled company will be able to contribute in this case, since it will not be contributing any property nor the rights to use subsoil, which are restricted too.

Moreover if this position could be solidly defended, we would see JVs being formed with State-controlled companies holding minority stakes, which is not occurring in practice. Finally, another obstacle for forming a JV with a State-controlled company is that in practice the latter will not be liable with its assets in case of any dispute because the law imposes a moratorium on compulsory sale of the property of State-owned companies, and there are also additional “temporary” immunities imposed by law for certain energy companies.

(B) For JAAs:

An investor will have no stake in and no control of the Subsoil License and such investor’s rights will be based exclusively on its civil-law agreement (JAA) with the State-controlled company, which will be the exclusive license-holder. Same as for JV, such JAA will require a specific individual approval by the GOU and a number of other approvals. Until recently there was no legal requirement as to what stake a State-controlled company must have in a JAA, but in 2011 the new legislation was enacted with regards to JAAs, establishing such stake at 50% or more.

This legislation also stipulated further restrictions, such as prohibiting contribution into JAAs of fixed assets of State-controlled companies that cannot be privatized (such as NAC Naftogaz), and requiring a tender for attracting investors into JAAs. Finally, same as with JVs, a Statecontrolled company in practice will not be liable with its assets in case of any dispute because the law imposes a moratorium on compulsory sale of the property of State-owned companies, and there are also additional “temporary” immunities imposed by law for certain energy companies.

One known practical example of GOU’s approval of a JAA is the Cabinet of Ministers Ordinance dated 10 December 2010 (and only published more than a month later) approving a JAA between State-owned joint stock company Chornomornaftogaz (a subsidiary of NAC Naftogaz) and Lukoil with regards to three subsoil areas on the Black See shelf: Odesskoe, Bezimennoye and Subbotinskoye.

The share of Chornomornaftogaz in this JAA must be no less than 50% and the JAA, after it is signed, must be submitted to the GOU for the final approval. Then it took more than a year to get this draft JAA approved by the Ministry of Energy, and only now it was reported that the JAA is ready for singing, but needs yet one more approval of the GOU!

In general the JAAs, which in practice have been the main investment vehicle in the Subsoil sector for years, were seriously compromised by various attacks by GOU and courts. In particular, the tax authorities keep insisting on their long-standing position that the rights of ownership to the extracted minerals may belong only to the license-holder, and such rights cannot be contributed (assigned) under the JAA to the investor.

The confusing and inconsistent attitude of GOU towards JAAs, as well as significant restrictions, in particular the new once enacted in 2011, remain a serious risk factor for using JAAs as a legal instrument for investment in oil & gas sector.

III. Production Sharing Agreements (“PSA”) Regime

(A) Changing the Rules of the Game

Ukraine’s PSA Regime was often praised by the investment community as being liberal and investor-friendly, and in particular letting investors conclude PSAs directly with the State without the need for a local partner.

In practice the only PSA Tender so far held in Ukraine for the Prikerchenska area was won by an IOC that had no local partner. Current GOU repeatedly warned the investment community that it was not happy that local partners were not imposed on investors in the PSAs, citing the example of Turkey where the national company Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO) has 50% stake in every project.

Finally in 2011, GOU changed the rules of the game, enacting Amendments to the PSA Law that in effect allow GOU to impose a local partner on the winner of the PSA tender, with the presumed obligation to fund the involvement of such local partner. The investors are not required to bid with the local partner, they can bid alone or in a consortia, with the local partner conveniently waiting for a winner to impose its involvement.

An interesting aspect is that this local partner is not identified in the law. It is vaguely defined as “commercial partnership [company], 100% of the authorized capital of which belongs to the State, or commercial partnership [company] created with its participation”. This awkward formula means that any company with any State-owned stake can qualify as the local partner.

The above Amendments to the PSA Law do not establish the size of the interest of the local partner in the PSA, but provide that the investor, which won the PSA tender, not the local partner, will be the operator of the PSA. Other than that the Amendments lack crucial details on how the relationship with the local partner will be structured.

These Amendments to the PSA Law undermined one more essential right of an investor, which was granted under the original PSA Law: to freely use its share of production, including exporting it outside of Ukraine. This right was important to investors because Ukraine is known to impose restrictions and price controls on domestic sales, in particular of natural gas.

Amendments to the PSA Law, however, provide that “in selected instances” the PSA tender conditions may contain the investor’s obligation to sell its share of production exclusively at the domestic market.

(B) Other Amendments to the PSA Law: stabilization clause restored; the PSA List removed.

Two other important Amendments to the PSA Law were also enacted in 2011:

• The so called “stability clause” allowing the investor to rely on the legislation in effect at the time of signing the PSA throughout the term of the PSA, which was removed from the PSA Law in 2010, was restored back. This development was unanimously welcomed by the investors, which consider guarantees against changes in the legislation for the duration of the PSA essential for such long-term and high-cost investment.

• The PSA Law contained a requirement that the Subsoil areas eligible for PSAs must be included in the list adopted from time to time by the Cabinet of Ministers (the “PSA List”). The PSA List had to be agreed in advance with local authorities, which were not always happy to unconditionally grant their agreement. In practice the GOU reportedly encountered strong resistance from the local authorities when it was trying to include the Olesska Shale gas area located across several regions in Western Ukraine into the PSA List.

In response, the Amendments to the PSA Law were enacted eliminating the PSA List altogether. This may seem as a liberalization measure, removing an extra approval, but although the local authorities can be removed from the stage of tendering Subsoil areas, which will make this stage easier for GOU, in practice they are not going anywhere. The investor will face them immediately as soon as it signs the PSA and starts its activities in the area, and will have to deal with them directly and find a compromise. Basically GOU shifted the burden of dealing with local authorities from itself to the investor.

(C) Practical Opportunities for PSAs: GOU Resolutions on PSA tenders for Yuzivska and Olesska Subsoil areas

Although the PSA Regime may be applied to any subsoil areas on-shore and off-shore, in practice it is understood that the PSA mechanism will be offered mostly for Black and Azov Sea Shelf (both shallow-water and deep-water) and for some Shale gas areas.

The current GOU chose to prepare the PSA tenders first for two on-shore areas, Yuzivska and Olesska (“PSA Tender Areas”), aiming at exploration and production of primarily Shale gas. Two relevant GOU Resolution on preparing PSA Tenders were adopted on 30 November 2011 (“PSA Tender Resolutions”).

In fact originally GOU planned to designate these PSA Tender Areas strictly for Shale gas, depriving potential investor of an opportunity to develop other types of hydrocarbons. The investors, however, convinced the GOU otherwise, and the PSA Tender Resolutions provide for development of various hydrocarbons that may be found in these areas (Shale gas, natural gas, CBM, crude oil and condensate), with the common understanding, however, that Shale gas would remain a priority.

Not surprisingly the GOU took advantage of the recently enacted Amendments to the PSA Law (described in sub-Section (A) above) on local partner and included the provision in the PSA Tender Resolutions imposing a local partner on the winner of the PSA tender. The GOU went further by requiring the winner to fund the involvement of such local partner and establishing its stake at 50%.

Again, the identity of this local partner is a mystery and the industry demands to know who it is and wants to perform due diligence on it before making a commitment, i.e. before bidding at the PSA tenders. We will know for sure when the PSA Tenders are announced, but according to unofficial information it will be NAC Nadra.

The winner of the PSA tender will have 120 days to conclude with the local partner a joint operation agreement or another agreement based on international oil and gas exploration/production practices. It is not clear what happens if the parties fail to reach an agreement within this timeframe, or in general. Moreover, such an agreement appears to be a pre-condition for concluding the actual PSA with the State, so the winner will have to negotiate on two fronts: with the local partner and with the State.

It should be kept in mind that the PSA Law establishes the 12-months term (with one possible 6-month extension) for negotiating the PSA with the State, and negotiations with the local partner may deduct 120 days (4 months) from the 12-months timeframe for the actual PSA negotiation with the State.

The PSA Tender Resolutions stipulate that the bidders must propose the ratio for the production sharing with the State in their applications, but do establish some parameters: the cost-recovery production is limited to 70%; the State share in the profit production must be at least 15% for Olesska area (16.5% for Yuzivska) of the total production, which if calculated together with the 50% share of the local partner, leaves the investor with 42.5% share in profit production (out of 100% of the total profit production the first 15% goes to the State, and the remaining 85% is evenly split between the investor and the local partner) .

The PSA Tender Resolutions also contain the minimal scope of investment required separately for the exploration and production stages.

The above terms and conditions of the PSA Tender Resolutions already caused protests from the investment community and relevant letters were sent to the GOU, simultaneously listing the industry’s other requests, such as international arbitration, waiver of the sovereign immunity by the State, etc.

But GOU decided to push the envelope a little bit further and let it be known, so far informally, that in the actual PSA Tender conditions it plans to decrease the cost recovery production from 70% to 45% and increase the share of the State in profit production from 15% to 45% (while the local partner will still claim 50% of the remaining production). This caused a new waive of protest letters from the investment community, with the end result to be known only when the PSA tenders are announced.

The upcoming Olesska and Yzivska PSA tenders will be an important test of how serious GOU is in terms of attracting investors and what level of GOU-favored conditions investors are willing

to tolerate.

IV. Shale Gas: Legal Status Changed

Shale Gas became a focus of attention in Ukraine’s upstream sector and many IOCs are looking into these opportunities or even announcing their shale gas plans. The GOU initially was caught unprepared for this active interest and is eager to learn from the experience of other countries, most notably the US and Poland.

To this end Memorandum of Understanding between GOU and the US Government on Unconventional Gas Resources was signed in 15 February, 2011. The purpose of the Memorandum is the exchange of knowledge and expertise in the fields of assessment and qualification of shale gas resources in Ukraine.

The GOU in 2011 has also fixed a loophole in the legislation, specifically designating Shale gas as a mineral of national significance by including it in the relevant GOU-approved list.

NOTE: The entire "Overview" article by Dr. Paliashvili can also be found in the attachment to this e-mail.

NOTE: RULG-Ukrainian Legal Group is a full-service law firm based in Kiev and Washington, D.C. that provides comprehensive legal support to international corporate clients doing business in Ukraine and other CIS countries. One of the RULG’s key practice areas is upstream oil & gas, both under Licensing Regime and under the PSA Regime.

RULG authored the production sharing legislation (two laws and a number of regulations) for Ukraine, which provided the legislative basis for the first ever Ukrainian PSA signed in October 2007. Detailed information about RULG practice is available at www.rulg.com. Dr. Paliashvili serves as Co-Chair, CIS Local Counsel Forum (www.rulg.com/cisforum). Dr. Paliashvili can be contacted at irinap@rulg.com.

The RULG-Ukrainian Legal Group is a long-time member of the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC), Washington, D.C., www.usubc.org. Dr. Paliashvili is a member of the USUBC Executive Committee.