Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

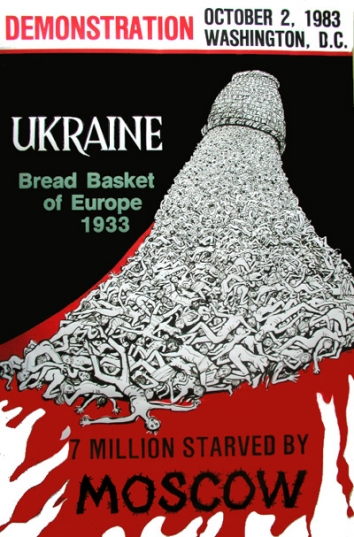

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

UKRAINE'S STALLED POWER

Kiev could achieve prosperity, independence and security if it got out of the way of domestic energy production.

Kiev could achieve prosperity, independence and security if it got out of the way of domestic energy production.

Opinion Europe: by Viktor Tkachuk,

he Wall Street Journal, NY, NY, Sun, Oct 17, 2010

This winter many Ukrainians may have to choose between putting food on the table and heating their homes. On top of the worst recession in modern history, the country faces an immediate 50% increase in household gas bills. State-subsidized gas has just come to an abrupt end.

What's particularly infuriating is the fact that Ukraine sits on potential gas reserves that would rival those in many Gulf States. But successive governments have done next to nothing over the past 20 years to verify and exploit these resources.

According to a report issued by BP in June, Ukraine has proven natural gas deposits of 0.98 trillion cubic meters—enough to make the country self-sufficient in gas for the next 20 years.

A further two to 32 trillion cubic meters of shale gas may lie close to the Polish border, and up to 8 trillion cubic meters of coal-bed methane gas may be in the Donbas basin, according to estimates made last year by former President Viktor Yushchenko's energy advisor Bohdan Sokolovsky and the Ukrainian government's National Agency for Energy Resource Management, though these reserves have yet to be commercially proven.

The Crimea also holds new natural gas fields, and the Black Sea has its own potential for off-shore hydrocarbons.

But instead of trying to exploit these potential domestic energy sources, Kiev has for decades weaned Ukraine's industry on cheap, plentiful gas imported from Russia and Central Asia. Meanwhile, foreign investors who might be tempted to help Ukraine develop its own domestic energy sources have, time and again, been scared off by a mercurial business environment and fickle governments.

Ukraine can no longer afford this complacency. In the first quarter of this year, Russia's Gazprom again hiked the prices it charges to Ukraine's cash-strapped state gas company, Naftohaz Ukrainy, meaning its tab soared to $305 per thousand cubic meters from $50 per thousand cubic meters in 2005.

According to investment bank Troika Dialog, that's just $2 less than Gazprom's European customers pay, even though Kiev buys gas at the Russian-Ukrainian border and thus doesn't have to pay the Asian, Russian or Ukrainian gas transit fees.

With the price of natural gas set to plummet over the next five years, Gazprom knows it will face stiff competition in Europe, both from natural gas importers and from producers of domestic shale gas.

Russian gas is very expensive to extract and transport, particularly from the newer fields in northern and central Siberia. Plentiful Ukrainian gas less than 800 kilometers from Europe's border, coupled with a ready-built pipeline network to transport it, perhaps explains why Naftohaz is being pursued so ardently by its northern neighbor.

The failure of successive Ukrainian governments to validate, quantify and exploit these reserves is nothing less than a betrayal of national interests. Major energy companies such as Shell, BP, Marathon, ExxonMobil, and Total, along with various Ukrainian politicians, have tried for years to negotiate deals for serious prospecting. However, president after president has failed to ratify the bills, and so the plans for geological surveys remain in their drawers.

Most recently, Kiev has stalled progress by removing a key clause from Ukraine's rules governing production-sharing agreements in public/private partnerships. Without the clause, the government can change the basic financial terms of contracts with foreign investors at any point.

As Shell's general manager, Patrick Van Daele, recently told the Kyiv Post, if the clause is not replaced, "nobody in his right mind will be willing to come and invest here." The legislation currently awaits President Viktor Yanukovych's signature.

You'd think the European Union would want to prod Kiev in the right direction, given that it could have in Ukraine a potential Gulf state on its own doorstep, and—at last—a major rival to Russian supplies. But, privately, many EU officials appear relieved that Ukraine's leaders seem to have put EU membership on the back-burner. As Europe slowly turns its back, Russia's influence grows.

So time is running out for the Ukrainian people. The current government is centralizing its power, even as the argument for real Ukrainian democracy has never been greater. Government transparency, accountability, and the rule of law would foster a safe and predictable environment for foreign energy investors. And in Ukraine's ability to exploit its own resources lies not just financial prosperity, but true independence and security to boot.

NOTE: Mr. Tkachuk, a former deputy secretary of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine, former senior presidential advisor and former member of the Ukrainian parliament, is chief executive officer of the People First Foundation.

LINK: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703794104575546041162286202.html?mod=googlenews_wsj