Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

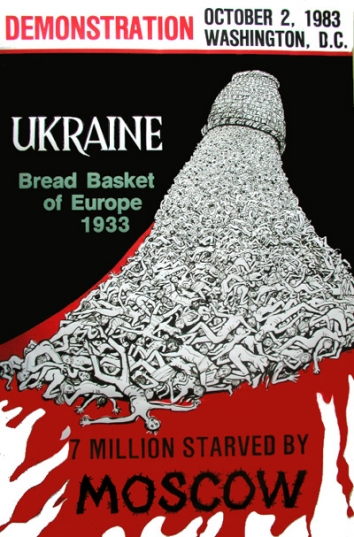

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

WHERE EAST MEETS WEST: EUROPEAN GAS AND UKRAINIAN REALITY

By Edward Chow and Jonathan Elkind, The Washington Quarterly, pp. 77 - 93.

By Edward Chow and Jonathan Elkind, The Washington Quarterly, pp. 77 - 93.

Journal of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Washington, D.C., January 2009

WHERE EAST MEETS WEST: EUROPEAN GAS AND UKRAINIAN REALITY

By Edward Chow and Jonathan Elkind, The Washington Quarterly, pp. 77 - 93

Journal of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Washington, D.C., January, 2009

NOTE: Edward Chow and Jonathan Elkind have written an article in the January 2009 issue of The Washington Quarterly. The article, entitled “Where East Meets West: European Gas and Ukrainian Reality,” explains how Ukraine is caught between the old, post-Soviet world and the new, European one that it desperately wants to join. By focusing on Ukraine’s natural gas industry, the authors have highlighted the dilemmas facing Ukraine and Europe, as it reconsiders Ukraine’s bid to join the European security community.

Edward Chow is a senior fellow in the CSIS Energy and National Security program and a former international oil industry executive. He can be reached at EChow@csis.org. Jonathan Elkind is a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and previously served on the staff at the National Security Council. He can be reached at jelkind@brookings.edu.

WHERE EAST MEETS WEST: EUROPEAN GAS AND UKRAINIAN REALITY

Ukraine is caught between the old post-Soviet world and the new, European one

On January 11, 2008, on the eve of the NATO summit meeting in Bucharest, the Ukrainian president, prime minister, and parliamentary speaker wrote to Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, asking that Ukraine be invited to begin a Membership Action Plan (MAP) leading to membership in the Alliance.

(1) In April, the NATO heads of state deferred the issue of MAP for Ukraine, and fellow aspirant Georgia, saying that progress should be assessed at the December 2008 NATO ministerial. (2) In that same month, after a tumultuous year of political recriminations and policy deadlock within the ruling coalition, Ukraine is also scheduled, to have its third pre-term parliamentary election in three years.

These events shine a harsh spotlight on the current policymaking environment in Kyiv, and also on the country’s longstanding aspiration to join the Euro- Atlantic community. At present, Ukraine is caught between the old, post-Soviet world and the new, European one that it says it wants to join. Nowhere is this clearer and more consequential, both for Ukraine and for the Euro-Atlantic community, than in Ukraine’s natural gas industry.

While Ukraine plays a critical role as the key transit connection between gas producers in Russia as well as Central Asia and gas consumers in the EU, its incomplete market economic transition and culture of corruption weaken its own energy security, destabilize its economy, destroy public trust in its politics, and undermine the interests of its European neighbors as well.

Worse yet, Ukraine’s leverage in the energy marketplace is eroding rapidly. A Ukraine that modernizes the practices in its energy sector can contribute significantly to European security, stability, and economic prosperity. Yet, this is not the role that Ukraine has played since 1991 and, even most disappointingly, not the role the country has played since the dramatic Orange Revolution brought new leaders to power in 2005.

Western leaders who have encouraged Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations would be well-advised to examine critically the current state of Ukraine’s gas sector, its implications for the country’s democratic development, and risks for European security as it considers Ukraine’s bid to join the trans-Atlantic community in 2009 and beyond.

UKRAINE'S ABUNDANT ENERGY POTENTIAL

Ukraine's corruption and incomplete economic transition weaken its own energy security - and Europe's

Ukraine’s energy situation is much more complicated and perilous than it should be. The country has a generous endowment of hydrocarbon resources both onshore and offshore in the Black Sea. It has a capable energy workforce, and long experience in the exploration, production, transportation, and refining of oil and gas. Most prominently, it is strategically located and has large-scale infrastructure.

Today, roughly 80 percent of the gas being exported from Russia to Europe crosses Ukrainian territory, roughly 120 billion cubic meters (bcm) per year. This gas originates variously in Russia and Central Asia, and it passes Ukraine en route to European clients who are the best-paying customers of the Russian gas titan, OAO Gazprom.

In fact, two-thirds of Gazprom’s revenue comes from the sale of gas that crosses Ukraine, which in turn represents more than 20 percent of growing European gas demand. Moreover, Ukrainian gas throughput can be increased by 25 percent, to roughly 150 bcm per year, on a cost-effective basis, with comparatively modest capital investment relative to all other alternatives.

Ukraine also has strategic strength in the form of other energy transportation infrastructure. Its oil pipeline network can transmit roughly one million barrels of oil per day (nearly 7 percent of total EU demand) to central and eastern European destinations. It also has immense gas storage capacity. The country can store up to 35 bcm of gas (roughly 40 percent of Germany’s annual demand) in underground gas storage systems, which are mainly located in the west of the country - an ideal location for serving European gas customers. Gas storage is a particularly valuable asset because it allows one to match supply, which is basically constant year-round, and demand, which often varies widely due to seasonal changes or other commercial or even strategic factors.

As for its domestic energy production, Ukraine has several hydrocarbon producing provinces onshore and has vast geological potential both on and offshore. Peak historical gas production was 68.7 bcm in 1975 (more than the total consumption of Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom at that time), compared to the current production level of 20 bcm.

Today there are opportunities for enhanced oil and gas recovery from Soviet-era fields plus previously untapped ‘‘greenfield’’ opportunities, especially in deeper producing zones and in the Black Sea. Industry experts, both inside and outside Ukraine, commonly believe that with improvements in the overall investment climate and with the right changes to the legal and regulatory environment, Ukraine could double its gas production within a decade.

ENDURING ENERGY INSECURITY

Ukraine's gas sector presents risks for European security.

Roughly 80 percent of gas exported from Russia to Europe crosses Ukrainian territory.

Despite this resource potential, strategic location, and existing infrastructure, the country struggles with energy security. The reasons are an incomplete transition to market economics, chronic underinvestment, and profound opaqueness of policymaking, which fuels corruption.

Seventeen years after the break-up of the Soviet Union, the energy economy of independent Ukraine is still frozen in seemingly permanent transition. The structure of the energy sector, particularly of the oil and gas industry, is a cross between a Soviet branch ministry and private interest groups. The state-owned company, NAK Naftohaz Ukrainy, contains many able and knowledgeable professionals but is overly politicized in leadership, overstaffed, mismanaged, impoverished, and operates under numerous fundamental conflicts of interest.

For example, one of the company’s wholly-owned subsidiaries, UkrTransNafta, operates the country’s oil pipelines and is responsible for determining the terms on which domestic crude oil is accepted into the system for transportation, including from private oil companies that have invested in exploration and production (E&P) activities. At the same time, other Naftohaz subsidiaries, some of which have controlling private owners despite being predominantly

state-owned, are also in the business of extracting crude oil. Naftohaz’s subsidiary UkrTransNafta, therefore, is determining pipeline access for private E&P investors even as they compete with other Naftohaz subsidiaries.

Price signals, the most fundamental element of a functioning market, are also profoundly confused and obscured in the Ukrainian energy sector. For example, in its current form, the gas industry employs multi-tier pricing that reduces incentives to conserve a precious resource and enables flourishing graymarket trading.

In other words, gas from domestic Ukrainian production is theoretically earmarked for use by residential customers and government-funded organizations at a subsidized price, while higher priced imported gas is meant to be used for industrial consumption. Not surprisingly, this schema is not honored in reality. Politically well-connected individuals and companies use barter arrangements and re-export schemes to profit handsomely while injuring the national welfare. Meanwhile, domestic gas production is depressed by artificially low prices.

Non-transparency reaches its peak in international natural gas trade and transit, where the poster child is the shady middleman, RosUkrEnergo (RUE). The company’s role is a political bone of contention in that an entity with no assets, no track record, and no transparency was placed at the very center of the Ukrainian gas economy.

Moreover, RUE did not even have to compete for this very lucrative position. It is also important to note that RUE was not the first mysterious middleman to operate in the Ukrainian gas sector. One therefore wonders: if RUE is thrown out, as the most senior Ukrainian officials have said they would like to do, would RUE simply be replaced by another nontransparent entity despite all declared policy to the contrary for supply contracts with Gazprom and Central Asian gas producers?

Similar to its predecessors Itera and EuralTransGaz (ETG), RUE makes a fortune by re-selling gas in Ukraine and in neighboring central European countries which has been imported from, or transported across, Russian territory. Under the January 2006 gas agreement, Ukraine pays RUE in kind by giving it more than 20 percent of the total delivered gas, which is 15 bcm of the 73 bcm that were nominally contracted for 2007.

The value of the in-kind gas in late 2007 was $4.35 billion, assuming a gas price of $290 per thousand cubic meters which was a representative price in central and eastern Europe at the time. Today, the value of this gas would be substantially higher, based on prevailing prices for gas. According to numerous press reports and industry rumors, RUE’s ample profits flow into the pockets of well-placed officials in the Russian and Ukrainian gas industries and governmental structures.

The Ukrainian oil and gas sector is dominated, some would say strangled, by parties that control investment decisions and cash flows, but who are not subject to the responsibility of ownership. Typically, company owners must comply with transparent government regulation and must exercise discipline in their operations to deliver financial performance for fear of being rejected by the capital markets on which the company depends. Instead, the parties who control the Ukrainian oil and gas sector use their positions to block development, to extract economic rent, and to pick commercial winners and losers for their personal convenience.

For example, only some projects get governmental approvals; only some companies get sought after contracts. Consequently, control over the sector is a major prize in political contests. When one political bloc is uppermost in national politics, no project proceeds without the blessing of, and benefits for, people connected with that bloc. When that group loses the political upper hand, deals are often subject to renegotiation. At the same time, it becomes the job of each successive political opposition to block all policy proposals, even the sensible ones, because the opposition is not profiting. As a result, few major long-term policy initiatives have been enacted or implemented.

One of the most damaging results of this pattern is chronic underinvestment in the oil and gas sector. Opportunities to raise production, increase efficiency, and improve reliability are lost because short investment horizons dominate. In infrastructure-dependent, capital-intensive, long lead-time industries like oil and gas, such actions severely damage the prospects for progress and development. Consequently, the condition of Ukraine’s oil and gas industry continues to deteriorate.

In May 2007, for example, one of the main gas transmission lines near Kyiv experienced a failure and exploded. Had the accident occurred in the winter, when cold temperatures hike demand and when all gas pipelines operate at peak levels, the incident could have had a major humanitarian impact. Instead, it only signaled the risks of underinvestment in operations, maintenance, and upgrades.

Ukraine consumes between approximately 60 and 75 bcm annually, which makes it the sixth largest gas consumer in the world, with consumption levels that are completely out of proportion to the size of its economy. (3) Its consumption equals that of all the Visegrad countries - Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia - combined. Its energy intensity is not only higher than Western European countries, but it is twice as high, or twice as inefficient, as neighboring Poland. Ukrainian officials and lawmakers make ritualistic comments about the need to reduce energy intensity, but the extent of real action is very limited.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

Three years after the Orange Revolution, the gas sector is no more transparent that it was.

In the wake of the 2005 Orange Revolution, President Viktor Yushchenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko declared high ambitions for energy sector reform, increasing public expectations. Three years later, none of the stated intentions and expectations has been met. Most conspicuously, the gas sector remains as convoluted and impenetrable as ever. In March 2005, Yushchenko declared that gas trade with Russia would be conducted on a cash basis rather than through non-transparent in-kind payments.

Yet, no proper negotiation process followed. Throughout the fourth quarter of 2005, tensions over the gas issue grew, and both Russia and Ukraine resorted to the gas equivalent of saberrattling. The Russians’ version of this high-stakes brinksmanship was to threaten to cut off gas supply to Ukraine. The Ukrainian version was to threaten to stop gas transit to Europe.

On January 1, 2006, Russia’s Gazprom reduced gas through put to Ukraine by an amount roughly equivalent to what Ukraine would have been entitled to extract if a contract were in place. In the midst of a bitterly cold winter throughout Europe, Ukraine apparently retaliated by taking unsanctioned gas from the pipeline system. Foreign governments, especially in Europe and the United States, reacted quickly, criticizing the Russian cut-off and calling for the

two sides to reach a negotiated settlement. Early on January 3, Russia returned the gas pipelines to normal operations, appearing to concede that it had lost the battle for international public opinion.

On January 4, Naftohaz Chairman Oleksiy Ivchenko and Ukrainian Minister of Fuels and Energy Ivan Plachkov announced a new gas agreement with Gazprom and RUE. To those who had been monitoring the mounting crisis, the agreement was as incomprehensible in its logic as it was unprofessional in its form. Regrettably, it also established the pattern for two subsequent years of negotiations. The result of the early 2006 negotiations was unfavorable to Ukraine inasmuch as it gave away the previously-agreed nominal gas price of $50 per thousand cubic meters and accepted a nominal price of $95.

In exchange for this concession, Ukraine did not receive an agreed pricing formula for future years, which would have removed the opportunity for politically-charged eleventh-hour negotiations. Nor did Ukraine receive agreement on a period for transition to higher prices or a long-term, ship-or-pay volume guarantee from the Russian side, nor any other enforceable contract provisions. Instead, the RUE import monopoly was expanded, and its non-transparent in-kind payment further entrenched.

Late in 2006, under a new government led by Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovich of the Party of Regions, Ukraine accepted a nominal price of $130 per thousand cubic meters for 2007. Late in 2008, the nominal price rose to $179.50, again without normal international contract protections. During the same period, both Belarus and Bulgaria successfully negotiated multi-year gas supply agreements with pricing mechanisms and multi-year periods for transition to ‘‘European’’ pricing levels with Russia.

Neither of these countries has negotiating leverage comparable to Ukraine’s, leverage which reflects the fact that 120 bcm of gas transit Ukraine annually from Russia to European consumers. For reasons that are inexplicable as a matter of basic negotiating leverage, Ukraine failed to secure self-protection that less powerful neighbors managed to secure with Gazprom.

Ukraine claims to receive gas, while Russia claims to sell gas, at nominal prices that do not correspond with reality. These nominal prices have deceived the Ukrainian public into thinking they were getting a better deal than they are, and have created a disincentive to engage in gas sector modernization, a faulty logic that is based on the fear that Ukraine could not survive economically if it were required to pay European gas prices. False prices and faulty contract compliance also allowed the Russian side to accumulate debt obligations from Ukrainian entities, thus setting the stage for predatory buy-outs by entities with the right connections (whether Russian, Ukrainian, or other).

The mechanism used to mask these false prices is simple. According to the terms of the January 2006 agreement, Ukraine pays a stated price (initially $95 per thousand cubic meters, then $130 for 2007, and $179.50 for 2008) to import up to 58 bcm of gas per year (roughly three-quarters of Ukrainian demand). To receive that volume of gas for domestic use, Ukraine must actually buy 73 bcm of gas, out of which 15 bcm is transferred to RUE for the ‘‘service’’ of delivering the total volume of gas to Ukraine. As a result, the actual price paid by Ukraine is significantly higher than the nominal price, since approximately one of every five cubic meters that Ukraine purchased (15 of 73 bcm) is actually being turned over to RUE, with its beneficial owners pocketing the handsome profits.

In 2007, gas was selling in several central and Western European countries for around $290 per thousand cubic meters on a delivered basis.4 In that same year, Ukraine paid the nominal price of $130 per thousand cubic meters for 56 bcm of gas that was said to be sourced from Central Asia, and Ukraine paid $230 for a further 17 bcm that was said to be sourced from Russia. In aggregate, Ukraine paid $11.19 billion for 73 bcm in 2007.

In exchange for that aggregate sum, Ukraine actually received only 56 bcm of gas for its own consumption, making the price Ukraine effectively paid in 2007 for each thousand cubic meter of the usable gas $192.93, not $130. Similarly, the real price in 2008 that corresponds to the nominal price of $179.50 is roughly $240 per thousand cubic meters. For RUE, this arrangement has been exceptionally lucrative. RUE has been able to re-sell at European market value the gas it receives as an in-kind transfer.

Certain Ukrainian industrial and export customers are willing to pay close to full value, which means that RUE can pocket literally billions of dollars per year.5 The reason behind RUE’s preferential place in the Eurasian gas trade has never been explained in comprehensible terms. Gazprom and Russian government officials have always blamed the Ukrainians while the Ukrainians have always blamed the Russians.

Nonetheless, the simple fact is that Gazprom allowed billions of dollars of value to flow into the pockets of a group of middlemen without demonstrable industry expertise and without compensating Gazprom’s shareholders, or Russian taxpayers, in any commensurate way. And the Ukrainian government and Naftohaz allowed RUE to occupy an absolutely central place in the Ukrainian economy, earning billions from the role, without ever having had to compete for the role or prove its capabilities in any way.

From time to time since 2005, Ukrainian officials have proudly asserted that they have extemporized skillfully, allowing their country to buy time and adjust gradually to higher gas prices. Unfortunately, such claims ring hollow. Three years after the arrival of Yushchenko and the Orange forces, the gas sector is no more transparent than it was in 2004, when RUE’s role was more limited. As of 2008, Ukraine still lacks the stability and predictability that would come from long-term gas contracts.

Ukraine also lacks the protections that would come from an international-style agreement that includes all the standard provisions that Gazprom routinely negotiates and concludes with its German, French, or central European counterparties -provisions such as take-or-pay obligations for gas buyers, ship-or-pay obligations for shippers, price adjustment mechanisms, clear arbitration provisions, and many more. Over the past three years, Ukraine’s negotiating leverage has eroded greatly.

Gazprom is three years closer to its objective of commissioning bypass pipelines that will allow it to transport more of its gas to Europe without having to cross Ukraine. Blue Stream, which passes under the Black Sea to Turkey, is operating at capacity while Nord Stream, which is meant to cross the Baltic to Germany, is proceeding, though not without a number of headaches. And South Stream, which is planned to pass under the Black Sea to Bulgaria, is now under development. All three of these routes will bypass Ukraine entirely.

Even without these pipelines being completed, Ukraine’s leverage is rapidly eroding. Naftogaz’s chronic and massive indebtedness - it is currently in technical default of its international bond obligations - makes Gazprom the only potential purchaser of its remaining valuable assets, namely the trunk gas pipeline and storage facilities. Gazprom’s dominant position gives Russia the possibility of taking over Ukraine’s decaying infrastructure and strengthening its control over gas exports to Europe, including those from Central Asia, even without having to construct all the bypass pipelines it is planning.

Although gas trade and transit carries the greatest international impact, they are not the only parts of the Ukrainian energy sector that remain distorted and dysfunctional. Domestic production is stagnant to declining at the time when it should be booming. Investment in exploration and production of Ukraine’s oil and gas resources, which could have been substantial at a time of historically high international prices and constrained access to new prospects, has amounted to a trickle at best.

The sole international competitive bidding for new development that occurred in this entire period, for the Prikerchenskiy offshore block in the Black Sea, has been a classic case of non-transparency, rent-seeking, and professional incompetence. First, in 2005, Ukrainian officials deliberately chose not to employ standard marketing techniques that are universally recognized as proven approaches to increase industry awareness of new prospects, and thus

increase potential bids from competing companies. Then in 2006, with the country experiencing political turmoil associated with imminent parliamentary elections, bids were collected under an ill-conceived process, and a small independent American oil company with modest experience in offshore west Africa, Vanco, was announced the tender winner.

In late 2007, with yet another new Ukrainian government about to arrive, the terms of the production sharing agreement (PSA) were concluded and formalized by the outgoing government. The timing struck knowledgeable industry observers as unusual, a long-term deal concluded in haste by a lameduck government just before its departure. Most observers assumed the deal would be overturned by an incoming government, and unfortunately they were

proven right.

In May 2008, it was officially revealed that Vanco’s Pricherchenskiy investor group includes the Ukrainian firm Donbass Fuel and Energy

Complex (DTEK), which is owned by Ukraine’s richest man, Rinat Akhmetov, the force behind the now-out-of-power Regions Party of Ukraine, as well as other mysterious entities whose ownership and expertise have never been revealed.

The second Tymoshenko government, in turn, cancelled Vanco’s license, allegedly due to problems in the fairness and adequacy of the tender process and license terms, which then led to an open disagreement between Yushchenko and Tymoshenko. In the summer of 2008, Vanco announced it would take the matter to international arbitration. The deputy head of the presidential secretariat stated to the press: ‘‘We do not have the right to revoke the license unilaterally.’’ (6)

This entire experience calls into question Ukraine’s interest in attracting transparent foreign investment into its upstream oil and gas industry. Despite numerous efforts, no major foreign investor has been able to achieve any success in Ukraine’s upstream oil and gas sector, including Royal Dutch Shell and Marathon.

The nature of the current investment climate should ring alarm bells in the ears of Ukrainian policymakers along with the leaders of the Euro- Atlantic community. If developing the country’s domestic hydrocarbon resources is a priority for Ukraine, as it should be, and if foreign investment is essential to the country’s ability to develop those resources in a timely manner, and it is, then it is important to acknowledge that, at present, the investment climate of Ukraine is highly unattractive.

IMPROVING UKRAINE'S OIL AND GAS SECTOR

In the long run, energy production, transportation, and distribution need to be unbundled.

Currently, Ukraine’s oil and gas sector is being operated in a completely dysfunctional manner. Yet, there are several beneficiaries, well-positioned individuals and key political forces, milking the energy sector, particularly the oil and gas industry, for personal enrichment and as sources for political funds. The present state of affairs underscores the most essential prerequisite for change in Ukraine’s oil and gas sector: political will. The needs of the nation, for today and tomorrow, are consistently overridden by short-term political expediency and personal gain, creating a corrosive effect on the entire political system, as it contributes to a broad loss of faith in the political process among the Ukrainian public.

The open and free press that has exposed the corruption underlying the oil and gas industry, however, is one of the truly important and hopefully lasting changes after the Orange Revolution. Today’s energy policy, which serves the interests of certain political elites rather than the country, poses imminent danger to the nation, yet it is not being addressed with any sense of urgency. To date, no political faction has demonstrated a willingness to put aside parochial interests for the good of the nation, a reality that must be changed if Ukraine is to pursue membership in the Euro-Atlantic community.

As experience around the globe will attest, sound energy policymaking is a difficult task. The United States, and many other political cultures that are far more settled than Ukraine, struggle to make good choices in energy policy. Effective energy policy requires political leadership, economic analysis, public dialogue, consensus building, commercial awareness, planning, and professional execution, not the enunciation of lofty goals.

Energy policy should be based on sound priorities, action plans, intermediate objectives, and realistic timetables. At present, Ukrainian officials betray a lack of seriousness on energy strategy, which undercuts the ability of commercial and public decision makers to plan energy-related aspects of their future, and reinforces already high public cynicism about the mishandling of the energy sector.

Gas supply and transit, which have been the source of so much controversy and intrigue since Ukrainian independence, must form the core of a sound Ukrainian energy strategy. Ukraine could credibly set the goal of reducing its reliance on imported gas from the current level of approximately 75 percent to 50 percent within the next five to seven years. Achieving this objective would require a range of efforts, some related to domestic supply and some to demand.

On the demand side, there is great scope for helping Ukrainians, particularly those living in multi-family apartment buildings, to simultaneously reduce their gas consumption and improve their comfort as well as quality of life by investing in energy efficiency. Another essential aspect of this initiative would be to reduce gas consumption by allowing gas prices to increase to full-cost recovery levels and by enforcing payment discipline. This is important because allowing the accumulation of gas debts only makes Ukraine vulnerable to highly disadvantageous debt-equity swaps.

In addition to reducing gas consumption, Ukraine could increase its domestic gas production. Eliminating multi-tiered pricing would encourage new domestic production, because domestic production is currently designated for sale to residential and budgetary-institution consumers, but at only a fraction of the true market value. The current practice discourages domestic production and subsidizes higher-priced imports.

For gas transit, Ukraine’s goal should focus on stabilizing its contractual relationship with Russia. At present, Ukrainian officials constantly declare that their country is a reliable transit partner, but a short conversation with virtually any European gas industry executive will reveal that this self-perception does not correspond to the understanding of industry experts outside Ukraine. Nearly seventeen years of post-Soviet experience have taught Europeans that Ukraine is the part of the supply chain that often leads to disputes, mutual recriminations, and endless charges and counters charges. It is the weak link.

It is hardly surprising that many Europeans conclude that it is better to pay lip-service to the idea of closer gas-related engagement with Ukraine rather than formulate policies that would lead to such engagement. At present, because of the legacy of Soviet-style gas contracts, Ukraine is Russia’s problem to manage. And Europe does not appear to object to this reality.

Ukraine can transform its reputation by developing policies that aim to improve its reliability as a transit partner. A first step would be to engage in a systematic internationally-sanctioned assessment of the condition and investment requirements of the Ukrainian international gas transit system (IGTS).

The assessment could identify opportunities to increase operating efficiency and reduce bottlenecks, serving as the basis for increasing Ukraine’s transit revenue by increasing throughput volume, and not by extorting higher transit tariffs as is often proposed by Ukrainian officials. Such a technical audit would be welcome and possibly funded by the donor community. Needed capital improvements can be financed by international credit according to modern business standards.

Ukrainian officials often complain that transit across their country is substantially less expensive than across many other European countries which occupy a far less strategic position in the supply chain, a fact borne out by analysis conducted by the Energy Charter Secretariat, among others. Transit across Ukraine, however, comes with an uncertainty premium that the market is no longer willing to bear. Ukraine would be better advised to build market confidence and increase its transit revenues by increasing volume first and only later by increasing transit fees if such increases can be justified by investments to improve reliability and increase capacity in the Ukrainian IGTS.

FIVE STEPS TO ENERGY SECTOR STABILITY

The essential prerequisite for change in Ukraine's oil and gas sector is political will.

To achieve the priorities outlined above, Kyiv can take five steps that will help stabilize Ukraine’s energy sector.

[1] First, Ukraine should seriously and professionally negotiate with Russia to reach new long-term agreements on gas supply and transit. At this writing, representatives of Naftohaz and the Government of Ukraine continue to negotiate with Russian officials and Gazprom over a future, multi-year gas agreement and a gas price for 2009. Senior officials from the presidential secretariat and the Tymoshenko government continue to use the gas issue as a cudgel to attack each other in hopes of scoring political points.

This is not only unproductive for the country but is also damaging efforts that aim to improve Ukraine’s reputation as a serious and reliable transit country. It is not clear from press reports whether Ukrainian representatives are pursuing a clear negotiating strategy that is informed by expert analysis and supported by duly experienced professionals in fields such as international business practice, law, and finance, or are simply building on old and inefficient policies and practices. In any case, it is hard to imagine why Russia would agree to a firm contract prior to the upcoming, pre-term parliamentary election in Ukraine. Yet, Ukraine’s winter gas supply and Europe’s gas imports depend on agreements that expire on December 31, 2008.

[2] Second, Ukraine needs to transform the state-owned company Naftohaz into a functioning commercial concern. Naftohaz dominates the Ukrainian oil and gas industry in the style of a Soviet branch ministry, and consequently simply hemorrhages money. The fact that Naftohaz remains dominant, despite its consistent financial losses, reflects a conscious dual choice on the part of successive rounds of Ukrainian legislators, cabinets, prime ministers, and presidents: first, the choice not to address the utter insolvency of the oil and gas sector and, second, the choice to engage in asset-stripping and rent-seeking.

Naftohaz is on the brink of bankruptcy due to the absence of necessary and crucial reforms in areas like gas pricing. The company is responsible for buying gas for the needs of Ukraine’s population, governments, and some industry, but is unable to collect payment from consumers in amounts sufficient to replace the consumed gas and operate the delivery system. As a result, Naftohaz’s finances have reached the breaking point. It borrows expensively in the debt markets, paying a high premium because of its non-transparent business practices and precarious financial position, and uses the funds for current operations instead of capital improvements.

The cycle repeats until Naftohaz is declared to be on the verge of bankruptcy, at which point the government finally steps in and bails out the company, declaring it to be too important to fail. The government then changes absolutely nothing in the way Naftohaz operates, and the whole corrupted process starts over again. Naftohaz received a bailout in early 2008 as the current government entered office but went right back to losing money hand over fist. By summer, a new bailout was already under discussion, and by early October, a new bailout priced at $1.7 billion was announced. (7) Unfortunately, there is no reason to believe that the pattern will not repeat itself yet again.

To end this vicious cycle, Naftohaz must be subjected to fiscal discipline. It needs to be able to charge its customers nothing less than the actual cost of the delivered fuel. In addition, Naftohaz and all its lenders must be informed that there will be no further government bailouts of the company. Naftohaz’s operations must be rid of non-core functions, and inherent conflicts among the various Naftohaz functions must be resolved once and for all. In the long run, the essential functions of energy production, transportation, and distribution will need to be unbundled, consistent with European reform efforts, and with creating a competitive market. In short, Naftohaz must be transformed so that it is no longer a big black hole.

[3] Third, RUE and other middleman firms must be removed. These firms impose a hidden cost not only on Ukraine but also on Russian taxpayers and Gazprom shareholders. RUE also introduces serious risks and instability into the European gas supply chain. In late April 2008, press reports about a possible new Ukrainian-Russian gas deal indicated that RUE was to be removed, with all wholesale gas to be purchased by Naftohaz while independent gas traders would serve the intermediary function between Naftohaz and end users. Depending on In the long run, energy production, transportation, and

distribution need to be unbundled. implementation, this arrangement could open opportunities for new intermediary companies to establish themselves in the same way as RUE and others did, with all the attendant risks that are discussed above.

[4] Fourth, Ukraine should promote efficiency by reforming pricing and helping consumers use less gas. The danger in multi-tier wholesale gas pricing is that domestically-produced gas, which is nominally designated for public and household consumption, may get sold on the gray market to domestic industrial users or export buyers who are willing to pay European prices. These illicit sales fuel corruption and muffle the market signal that would otherwise promote increased domestic production and decreased consumption. Serious pricing reform is required - based on a sensible, transparent, and easily understandable rate methodology that allows gas producers or sellers to recoup their costs plus a reasonable rate of return.

Price formation will require capable and independent regulators to operate in a publicly transparent fashion so that the interests of producers and consumers are adequately balanced and duly protected. Price reform will mean higher prices all across the Ukrainian economy, which means the potential for negative impacts on the poor, namely those least able to pay higher prices. In order to lessen the impact on the poor, Ukraine should follow the example of other eastern and central European countries that have already undergone price reform.

Energy efficiency programs can help reduce the energy consumption of residential and institutional buildings as a first priority. Lending programs can be created, expanded, or strengthened to allow Ukrainian industry to borrow money in order to invest in upgrades for plants and equipment. And targeted assistance can be introduced to alleviate the burden on those legitimately unable to pay. The current system unfortunately operates in the interest of well-connected gas consumers and penalizes the poor who suffer shortages - making reform a necessity.

[5] Finally, Ukraine needs to improve its investment climate for exploration and production of hydrocarbons. If natural resource endowments were the only relevant factor, Ukraine would be able to produce significantly greater quantities of oil and gas than it does today. Significant improvement to the business climate, however, is required to attract the investment of billions of dollars needed for serious upstream development. Ukrainian energy legislation and regulation will need to be updated to correspond with norms found elsewhere around the globe.

The updated system will need to provide for fair access to geologic data, transparent decision making processes, longer licensing periods, use of model contracts, and truly competitive tenders. In other words, almost all of today’s standard practices, which are optimized for insiders and those paying for inside access, would need to be replaced. This will take time. Meanwhile, Ukraine will need a success story or a demonstration case that can prove the country’s new political will to encourage upstream investment.

THE KEY TO EURO-ATLANTIC ASPIRATIONS

Ukraine is a country generously endowed with many assets. Its well-educated population of 46 million, industrial and technological prowess, huge agricultural potential, and cultural wealth all make it a natural candidate for the Euro-Atlantic community, if that is the wish of its people. The current form of the country’s energy sector, however, needs to be seen for what it is, a major threat to itself and to its neighbors. If Ukraine fails to modernize its energy sector practices, the sector will continue to undermine Ukrainian politics, economy, and energy security. Most importantly, it will threaten Europe’s own energy security.

Ukraine has the potential to change this story line. Friendly governments and international institutions can help with capacity building for effective policy execution, but only after the political will for energy reform is in place. Serious energy sector reform would not only help Ukraine but would also stabilize the economic undergirding of all European gas importing countries.

In this sense, serious energy reform would arguably be Ukraine’s single most important contribution to improve the security of the trans-Atlantic community. On the other hand, continuing failure to engage in energy reform, when the high stakes are so obvious to all, would be a clear signal that Ukraine is not ready to pursue its stated desire of becoming a more integral part of the Euro-Atlantic community.

NOTES:

1. Press Office of President Viktor Yushchenko, ‘‘Joint Address to NATO Secretary General’’, January 11, 2008, http://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/8645.html.

2. Bucharest Summit Declaration, April 3, 2008, http://www.nato.int/docu/pr/2008/p08-049e.html.

3. Gas consumption figures drawn from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2008, available at http://www.bp.com/productlanding.do?categoryId 6929&contentId 7044622. GDP figures are purchasing power parity estimates, drawn from CIA’s World Factbook, available at https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html.

4. To compare (in a rough manner) the price of gas delivered to a given European country X and the price of gas delivered to Ukraine, one needs to subtract from the gas price in country X the price of transit from Ukraine’s eastern border to country X. For example, in January 2007 Russian gas delivered to France cost on the order of $295 per thousand cubic meters. If one deducts gas costs of transit between Russia and France, the comparable price in Ukraine would have been roughly $230. This is only an indicative comparison and should not be interpreted as implying that there is a standard or an ‘‘accepted’’ gas price in Europe. Gas prices under a given contract reflect the full range of factors from competitive gas supply to quantity of demand, and from available alternative fuels to skill of the commercial negotiators.

5. Since Ukrainian regulators never based their rate-making calculations on the actual price of gas (rather, they used the nominal price for their calculations) Ukrainian customers never paid the actual replacement cost of the gas they consumed. This fact allowed debt to pile up, which then provided the basis for more non-transparent deals.

6. ‘‘Ukraine president suspends cabinet’s decision to control top state companies,’’ BBC Monitoring Kiev Unit, May 20, 2008.

7. Alexander Bor, ‘‘Ukraine Orders $1.7 billion Naftogaz Bailout,’’ Platts Oilgram News 86, no. 198 (October 7, 2008): 7.

LINK TO THE ARTICLE: http://twq.com/09winter/docs/09jan_ChowElkindpdf.

TO SUBSCRIBE: to The Washington Quarterly go to http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t794176680~db=all?tab=subscribe.