Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

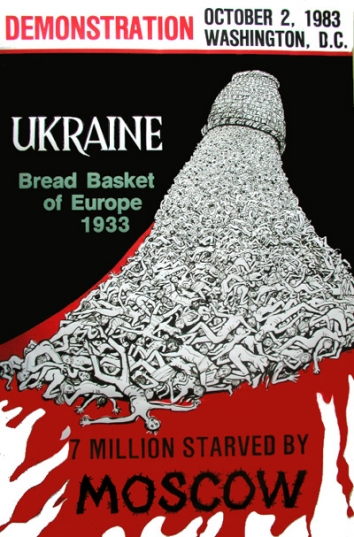

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

A Dilemma in the Crackdown on Corruption in Ukraine

Move too slow and get accused of indulging the oligarchs.

Move too slow and get accused of indulging the oligarchs.

Move too fast and the coalition government might crumble.

By Adrian Karatnycky -- The Wall Street Journal

New York, NY, Wed, Jan 6, 2016

With Russia’s aggression in the Donbas region of Ukraine having morphed into a frozen conflict, Ukraine’s President Petro Poroshenko now confronts a new challenge. He must address rising calls from the public to root out corruption while ensuring that such a campaign doesn’t lead to instability or bring down his government of technocrats and reformers.

For most of its 25-year history, postindependence Ukraine has been beset by massive corruption and rent-seeking. This deformity was a major catalyst for both the Orange Revolution of 2003 and the Maidan protests of 2013-14 that ended the authoritarian rule of President Viktor Yanukovych.

Public discontent has focused on the perception that complex privatizations, preferential tax breaks and long-term sweetheart leases of state assets have benefited favored individuals. But a determined attack on these privileges means confronting powerful lobbies inside Parliament, including members of the fragile governing majority. There is also the problem of avoiding the collapse of industrial and financial empires made shaky by steep economic decline.

On the other side, there is mounting public anger. A civil society giddy from toppling the Yanukovych regime and empowered by the role it played, alongside volunteer fighters, in staving off Russia’s military offensive in the Donbas has embraced a maximalist agenda for good governance.

Well-armed, far-right groups have also entered the fray, denouncing the “regime of internal occupation,” by which they mean an allegedly corrupt officialdom, that must be toppled by any means necessary. Rising populism, vigilantism and political violence all are part of this inflamed atmosphere.

It is primarily the responsibility of Mr. Poroshenko and Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk to accelerate their attempts to crack down on corruption. But civil society must also be more pragmatic. It does no good to demand that all corrupt practices be punished at once. Civil society must understand that the government’s vacillation in challenging Ukraine’s wide array of rent-seeking oligarchs reflects the complexity of Ukraine’s democratic politics and the administration’s precarious Parliamentary majority.

Already Mr. Poroshenko and the government have challenged important areas of oligarchic privilege, especially by creating a single, market-determined price for oil and gas. In doing so they have directly attacked the interests of some important backers of the parties that have been part of his ruling coalition.

Since the authorities took on billionaire Ihor Kolomoysky, by eliminating a legal loophole that allowed him to control a state oil company despite holding a minority stake, more than a dozen deputies linked to the oligarch have exited the ruling coalition to join the opposition, as did the Radical Party, a small populist group rumored to be linked to the businessman but which has denied any connections. Mr. Kolomoysky has launched a lawsuit in a London court to collect what he claims are vast Ukrainian government debts from gas that he supplied to the country. Mr. Kolomoysky also launched his own political party and cemented a coalition with the far-right Svoboda party, which denounces the current government for “treason.”

With the government weakened by the defection of some of its members of parliament and increasingly reliant on the cooperation of politically ambitious rivals, it’s clear why Ukraine’s president and prime minister must balance the need to confront oligarchic excesses with the need to preserve their majority. The collapse of the majority would usher in a far more populist legislature and threaten the fiscal and economic progress that has earned the endorsement of the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the European Union and the U.S.

Unfortunately, activists from civil society, many of them Western-funded, as well as some reformist members of Parliament, are often part of the problem. Having grown up in a Ukraine beset for decades by massive corruption, semiauthoritarian and authoritarian rule, they are schooled in the habits of aggressive opposition.

Such zealous reformers equate government foot dragging with collusion in corruption and continue to make sweeping and often unsubstantiated claims of criminal behavior against the prime minister, important members of the government and the presidential administration. Many refuse to acknowledge dramatic and tangible improvements in political freedoms and economic reforms and instead make unsubstantiated claims about a secret pact between the oligarchs and Ukraine’s rulers, about corrupt machinations, and about the ineffectiveness of reforms. This reflexive adversarial stance and its penchant for revolutionary rhetoric risks feeding the public cynicism on which extremism and populism thrive.

Ukraine needs a version of Poland’s “self-limiting revolution.” A slogan coined in 1980 by the Polish dissident leader Jacek Kuroń, it addressed the need for the Solidarity movement to adopt an evolutionary path despite a rising public desire for maximalist revolutionary policies. After martial law, this self-limiting ethos enabled Poland to find a path of national reconciliation and unity and fueled what has become one of Eastern Europe’s fastest-growing economies.

A settlement of this sort would have several components. The government and president must step up the pace of anticorruption prosecutions. Business leaders should unilaterally and voluntarily renounce some of their most egregious privileges, including excessively generous transportation subsidies for certain commodities and long-term sweetheart leases of government assets. Civil society should make clear that its aim is the reform of the market system and not the destruction of its central economic players. Civil society should also determinedly denounce those who challenge the legitimacy of Ukraine’s democratic leadership and preach revolution.

Ukraine can ill-afford to undermine the stability of its state, which is the only instrument for defense against a foreign aggressor and the only legitimate mechanism by which to implement reform. A national consensus anchored in this understanding is Ukraine’s best path forward.

Mr. Karatnycky is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council and co-director of its Ukraine in Europe initiative.

LINK: http://www.wsj.com/articles/a-dilemma-in-the-crackdown-on-corruption-in-ukraine-1450817045