Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

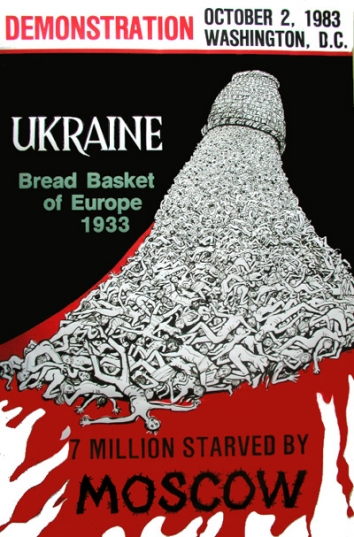

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

A Plan for NATO to Get Serious About Russia

.png) By Ambassador Kurt Volker, Fri, May 21, 2021

By Ambassador Kurt Volker, Fri, May 21, 2021

CEPA, Washington, D.C.

Kurt Volker serves as a Senior Advisor to USUBC

When NATO heads of state and government gather in Brussels next month, they will have a wide and complex agenda.

But while the Alliance has a pressing need to agree on positions on issues ranging from preventing disaster in Afghanistan to confronting China and maintaining progress towards spending 2% of GDP on defense, perhaps the most urgent issue is the need to forge a coherent transatlantic strategy to confront Russia’s growing threat to U.S. and European interests.

Until now, Russia policy has been piecemeal. While Allies have often pushed back against Russia’s worst excesses, such as seizing territory and using chemical weapons for assassination attempts inside EU states’ territory, they have been solicitous toward Russia in other areas, such as energy.

Policies have varied widely country-by-country and have often left tough rhetoric unmatched by tough action. Russian President Vladimir Putin has successfully taken advantage of this incoherence, encouraging divisions among Allies.

NATO leaders have repeatedly underlined that the Alliance has a uniquely important role to play as “an essential forum for consultation among its members, and the venue for agreement on policies bearing on the security and defense commitments of its members under the Washington Treaty”. For over 40 years during the Cold War, Allies maintained a common front in dealing with an existential threat from the Soviet Union. But for more than a decade, such unity has been largely absent.

After the Cold War, NATO made persistent efforts to build a new partnership with Russia, including through the NATO-Russia Founding Act and Permanent Joint Council (1997) and the creation of the NATO-Russia Council (2002). But as Russian behavior became more hostile (as with Russia’s disingenuous attacks on NATO missile defense plans and suspension of adherence to the Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, or CFE, Treaty in 2007), divisions emerged. The U.S. and Central European Allies were aghast at Russian behavior, while West Europeans believed the U.S. and the West should accommodate Russian concerns.

Even though Russia’s 2008 invasion of Georgia momentarily drove Allies back into a common posture, splits reemerged within six months as the new Obama Administration and several West European Allies sought a “re-set” with Russia, while Central and Eastern European members continued to demand a tougher line.

Partly as a response to Russia’s invasion— and partly to assuage Central European members who wanted to show support for nations in eastern Europe vulnerable to Russian pressure — in 2009 the EU launched the Eastern Partnership Initiative, aiming to strengthen engagement with Georgia, Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Armenia, and Azerbaijan.

The 12 years since the launch of the EU’s Eastern Partnership have been instructive. Russia has now placed troops on the territory of every Eastern Partnership country in one form or another: continuing to occupy parts of Georgia and maintain a garrison in Moldova without host-nation consent; attacking Ukraine and annexing Crimea while continuing to stoke fighting in Donbas; expanding a military base in Armenia; positioning “peacekeepers” on Azerbaijani territory in Nagorno-Karabakh; and engaging in a hybrid security presence and assertion of authority over Belarusian security forces. The EU has barely shrugged its shoulders at this Russian military assault on its own initiative.

Other forms of Russian aggression are almost too numerous to mention.

- The poisonings of Alexander Litvinenko, Sergei Skripal and Alexei Navalny

- Widespread interference in other countries’ elections

- Active disinformation in Western media

- Bombings and manslaughter at explosive depots in the Czech Republic and likely Bulgaria

- Bribery of Western politicians

- Air and sea space incursions of NATO territory

- Dangerous maneuvers around NATO aircraft and naval vessels in international waters

- Denying freedom of passage to shipping in parts of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

The list goes on.

The last time NATO leaders met was in London in December 2019, when relations between President Donald Trump and French President Emmanuel Macron, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau were at a low point, and President Trump was the subject of an impeachment inquiry in the United States.

2021 is different. President Joe Biden has made clear his desire to rebuild relationships. Indeed, the Administration’s recent decision not to sanction Western companies involved in Nord Stream 2 over their collusion with Russia in circumventing Ukraine and Central Europe, while increasing West European reliance on Russian gas, can only be read as a gesture toward Germany.

So, the question for the June 2021 NATO Summit is whether Germany will reciprocate this gesture. Can the United States, Germany, France, allies in Central Europe and the Baltic States, as well as those in southern Europe and Scandinavia, all come together to define a common assessment, vision, and strategy in dealing with Russia?

Russia’s aggression against Europe is the most serious and immediate threat to all NATO countries. The time is long overdue for a common strategy to push back.

Three policies would be transformative:

- The Czech Republic has taken a time-honored, but nonetheless bold step in limiting the number of Russian diplomats in its territory to the number the Czech Republic has in Russia. Will all Allies join the Czech Republic in the assertion of basic diplomatic reciprocity?

- Will Allies double-down on their commitment to spend 2% of GDP on defense, even amid post-covid-19 difficulties?

- Will NATO reaffirm its existing policy under Article 10 of the NATO Treaty to open its doors to all European democracies sharing its values and able to contribute to common security? Ukraine and Georgia in particular are freedom-loving societies that just happen to be geographically inconvenient. Yet people in Tbilisi and Kyiv have as much right to security as people in Berlin, Paris, and Brussels did a generation ago, as difficult as that was for the United States to commit to. NATO must finally commit to an “open door” and mean it.

The NATO Summit on June 14 will define the future of NATO for the rest of the Biden Administration. With a renewed U.S.-German alignment at the core, there is a chance to set a new, bold course to secure Europe’s future. Now is the time to do it.