Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

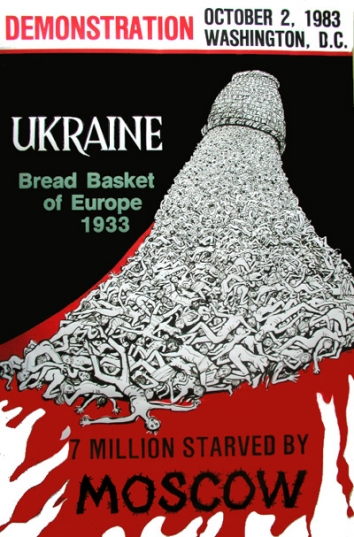

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

A VIRGINIA FAMILY’S PUSH TO GIVE

A UKRAINIAN ORPHAN RESPITE FROM WAR

Jenny Bradshaw, along with dozens of other families, wants to give young Ukrainian orphans a break in the United States

Jenny Bradshaw, along with dozens of other families, wants to give young Ukrainian orphans a break in the United States

The “Ukrainian government has been clear that adoption is not possible at this time, and they are not approving children to participate in host programs in the United States.”

By Dana Hedgpeth, Washington Post

Wash, D.C., Sun Jul 24, 2022

A Centreville, Va., family wants to eventually adopt Katya, a 9-year-old- Ukrainian orphan who's shown during her visit with them last year. (Jenny Bradshaw)

Shortly after they met the energetic brown-haired, blue-eyed 9-year-old girl from Ukraine, Jenny Bradshaw, her husband and their 17-year-old twin daughters were smitten.

They had thought about and researched the possibility of adopting an orphan from overseas and realized after a month-long exchange program in December with Katya at their home in Centreville, Va., that it was the right time. She fit in well with their family.

Katya — whose full name is not being used for safety reasons — enjoyed helping load the dishwasher, cook eggs, bake cookies and play dress-up. She had fun going to parks and museums and helping feed the family’s dogs. The family took her to a semiprivate Russian ballet class during her stay and Bradshaw said she “loved it.”

But since the Russian invasion of Ukraine this year, the family’s efforts to adopt her have been stalled.

More than 200 adoptions are completed every year from Ukraine to the United States, according to State Department statistics. But those have stopped because of the war, adoption experts and State Department officials say.

Now, Bradshaw and her husband, Holt, are part of a group of would-be parents in the United States who are lobbying Ukrainian adoption authorities, officials at the State Department and congressional leaders to try to raise awareness of their plight. And while the families wait for the normal adoptions to resume, they want the dozens of Ukrainian orphans like Katya who have already done exchange programs in the United States to be able to come and stay a few months with them.

“We’re not asking for a special exception or to skirt around the full adoption process,” Bradshaw said. “We just want to give her a break and respite from the war.”

Jenny Bradshaw with Katya in her kitchen during a visit. (Jenny Bradshaw)

Becky and Terry Shinault, who live near Harrisburg, Pa., said they’re hoping to do the same and give another young Ukrainian orphan a few months’ stay in their home and away from the war zone.

They hosted the teen, whom they call K and whose full name is not being used for security reasons, twice in the past year for brief stays during an exchange program, and decided afterward that they wanted to adopt her.

The exchange programs are designed to give the children a taste of American life and a break from their respective orphanages. They don’t encourage or discourage adoption but merely allow the Ukrainian children and their American families to experience other cultures, according to the U.S. families and officials who run them.

Shinault recalled how fun it was to see K, who recently turned 14, learn to swim, speak English and enjoy the family’s dogs and horse.

“She enjoyed being an only child and getting all the attention and getting a break from all the other kids,” Becky Shinault said. They had planned to host her again this summer through the exchange program, but the war broke out.

For now, the Shinaults desperately want to get K out of Ukraine — even if temporarily. K had been living at an orphanage in Mykolaiv, near the Black Sea, and was evacuated on the first day of the war to another facility in western Ukraine, according to Becky Shinault. She said she is able to sometimes talk to K in online message chats, using Google Translate to communicate, but the internet and power are often spotty.

“She recently wrote us and said she misses us ‘very much and wants to come to us,’ ” Becky said. “But she said, ‘This war does not allow me to fly to you.’ ”

Terry Shinault, who lives near Harrisburg, Pa., plays a game with K, a young Ukrainian orphan girl who came for a visit through an exchange program. Now his family is trying to give her a respite stay in the United States from the war. (Becky Shinault)

Rep. Jennifer Wexton (D-Va.), one of the leaders on Capitol Hill who met the families in D.C., said in a statement that she applauds “the efforts of these families who are trying to protect and provide for Ukrainian orphans.” She added that “it is my hope that conditions improve very soon so that intercountry adoptions can resume.”

Officials with the State Department said in a June letter to Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.) that they had been in touch with the Ukrainian Ministry of Social Policy and the Ukrainian Embassy in D.C.

David Bonine, a senior official in the State Department’s Bureau of Legislative Affairs, wrote in the letter that his department “has conveyed that many U.S. families want to continue the adoption process and to temporarily host children in the U.S.”

But he said the “Ukrainian government has been clear that adoption is not possible at this time, and they are not approving children to participate in host programs in the United States.”

Attempts to reach adoption and orphanage officials in Ukraine and Romania were unsuccessful.

Experts said it is not uncommon for adoptions or exchange programs to stop during and right after natural disasters, wars or other emergencies because there’s such a high risk of parents or other relatives showing up once a situation calms down. There also is a high risk of children falling into human trafficking circles.

Kelly Dempsey, a lawyer in Charlotte who has done international adoptions for 15 years, said there are at least 40 families in the United States who are in similar situations and want to provide respite care to orphans they’ve previously met through exchange programs. She said the families have already gone through the necessary background checks, home visits and other approvals when they served as host families for Ukrainian orphans, and many of them were in the midst of the adoption process when the war started.

A drawing done by Katya. (Jenny Bradshaw)

“We disagree that these kids should be separated from American families they know,” said Dempsey, whose clients live across the United States and are trying to help Ukrainian kids who range in age from 6 to 17 years old.

“The short-term solution is to allow the children to come on temporary visas to the U.S. and return only when it’s safe and then resume the adoption process,” Dempsey said.

“If we can take them out of bomb shelters, refugee camps and other dangerous situations and put them in the homes of families that they know and that love them, that’s certainly better.”

For now, Katya — along with the other orphans in her facility — was relocated to an orphanage in a town in rural Romania. Bradshaw went this spring to visit her and let her know, she said, that “her American family hasn’t forgotten her.” She said Katya showed her how she’d learned to use roller skates.

“We hugged,” Bradshaw said, “and she clung to me.”

NOTE: Dana Hedgpeth is a Washington Post reporter, working in the early morning to report on traffic, crime and other local issues. She joined The Post in 1999. She's American Indian and an enrolled member of the Haliwa-Saponi tribe of N.C. Razzan Nakhlawi contributed to this report.

LINK: A Virginia family’s push to give a Ukrainian orphan respite from war