Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

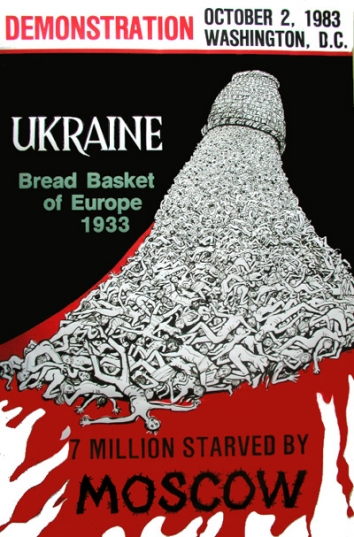

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

AMERICA COULD HAVE DONE SO MUCH MORE

TO PROTECT UKRAINE

Analysis & Commentary

Analysis & Commentary

by Alexander Vindman

The Atlantic

Washington, D.C.

Thu, Feb 24, 2022

Russia has launched another invasion of Ukraine. Countless Ukrainians and Russians will die. Countless more will flee. The economic and geopolitical second- and third-order effects of this war will not be fully understood for some time. The idea that this war can be quarantined will prove to be a pipe dream.

Russia has launched another invasion of Ukraine. Countless Ukrainians and Russians will die. Countless more will flee. The economic and geopolitical second- and third-order effects of this war will not be fully understood for some time. The idea that this war can be quarantined will prove to be a pipe dream.

This moment might be surreal were it not for the overt warning signs. The Kremlin built up Russian forces along Ukraine’s borders even as it issued maximalist demands and shut down diplomatic off-ramps. Long-term geopolitical trends—such as Ukraine’s decisive pivot to the West and Russia’s irredentism—shaped the contours of conflict. Meanwhile, the Biden administration progressively raised the alarm about the Kremlin’s likely course of action. But even if this conflict was foreseeable, that does not mean it was inevitable.

After Ukraine became independent and forfeited the world’s third-largest nuclear arsenal, the West could have loosened the purse strings to guarantee the country’s economic independence. After the 2004 Orange Revolution, the West could have embraced Ukraine’s Western aspirations, accelerated an EU Association Agreement and a NATO Membership Action Plan, and driven domestic transformation to shield Europe’s largest country from nascent Russian revanchism. After the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, the West could have invested in a strategic security partnership with Ukraine that would have made the costs of a Russian offensive prohibitively high. Yet none of this came to pass.

Instead, for two decades, the U.S. entertained illusions about what might be accomplished with Russia, a reluctant partner, while remaining oblivious to opportunities in Ukraine, a far more willing one. In its relationship with Russia, the U.S. had limited prospects of achieving any objectives outside of arms control, whereas with Ukraine it might have successfully influenced regional development.

The seed of this conflict was planted many years ago, across multiple Republican and Democratic administrations. But the Biden administration and its successors will own the geopolitical consequences of this war.

Undoubtedly, things could have been worse—one need only imagine a world where the former president was still in office. I acknowledge that the Biden administration reacted to the warning signs with consistently powerful statements about the U.S. commitment to the safety of U.S. citizens abroad, its resolve to defend NATO’s eastern flank, and Ukraine’s right to sovereignty, territorial integrity, and self-determination in the international system. The Biden administration also marshaled unity among U.S. allies, though it remains to be seen whether the promised sanctions and security measures will materialize.

Nevertheless, U.S. leaders cannot absolve themselves of guilt by claiming they did all they could to prevent another invasion; they offered a necessary response, not a sufficient one. Like every administration since the end of the Cold War, Joe Biden’s fell victim to wishful thinking about the Kremlin’s ambitions in Ukraine and Russian President Vladimir Putin’s basic commitment to international norms. In doing so, the Biden administration continued the decades-long practice of allowing deterrence to erode. The paths to prevention were not taken.

For instance, early in December, President Biden openly acknowledged that he would not send American troops to fight in Ukraine, thus removing any possibility of strategic ambiguity. The U.S. could have refused to elucidate its security commitments to Ukraine, much as it has done vis-à-vis Taiwan for decades. The implicit threat of U.S. and NATO intervention would have forced Putin to contend with the risks of further escalation. Instead, Biden granted Putin a free hand.

The U.S. also refused to provide advanced weapon systems to Ukraine, such as Patriot anti-aircraft missiles or Harpoon anti-ship missiles, because it determined that Ukraine’s armed forces were not sophisticated enough to handle them. Although Ukraine would have struggled to realize the full potential of these systems, they could nonetheless have affected Russia’s calculus for military operations. And for those who might argue that Russia would have preempted the shipment of weaponry by invading, I would contend that if invasion was already the predicted outcome, what was there to lose?

All the while, the Biden administration failed to pair diplomatic overtures with sufficiently powerful, credible military pressure, perhaps over fears of a bilateral conflict with Russia. These fears were misplaced. I can say from my significant experience dealing with the highest levels of Russia’s military leadership that it has no interest in a bilateral confrontation with the U.S. Russian leaders have zero desire for nuclear war, and they understand that they would inevitably lose in a conventional war. However, Russia excels at compelling the U.S. to self-deter.

Besides military pressure, the U.S. also failed to consider graduated response options once Putin’s preferred course of action had been established. The U.S. could have imposed targeted sanctions on Russian leadership or introduced long-overdue anti-corruption legislation to signal the impending costs of reinvasion to the Kremlin. By choosing to view these options through an all-or-nothing lens, the U.S. unnecessarily constrained its response. Biden’s administration was reactive when it should have been proactive. Over and over, the president’s longtime senior advisers seem to have recommended narrow, low-risk policy options, and these backfired.

Unlike during the Cold War, when the U.S. successfully deterred the Soviets for decades, the U.S. has now implicitly recognized Russia’s sphere of influence and perhaps undermined its own role as the most powerful global protector of democracy. This war marks the single biggest reversal of trends in the Western liberal order in the 21st century. Long-term tremors have culminated in a seismic shift that has injured both Western credibility and the foundations of international treaties. Overnight, the geopolitical outlook has become significantly worse for U.S. national-security interests, and now the U.S. must manage the fallout accordingly.

NOTE: About the author: Alexander Vindman is a retired U.S. Army lieutenant colonel and the former director for European affairs for the National Security Council.

LINK: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/02/ukraine-russia-war-nato-biden-deterrence/622873/