Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

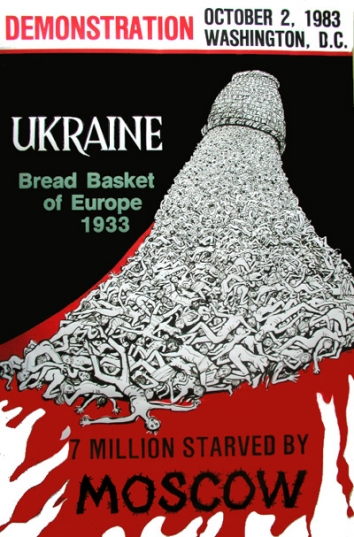

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

EVERYBODY IN WASHINGTON WANTS

THE UKRAINIAN AMBASSADOR AT THEIR PARTY

Oksana Markarova is hitting the town

Oksana Markarova is hitting the town

like her country depends on it

By Ben Terris, Washington Post,

Wash, D.C., Tue, Apr 4, 2023

(Agnes Lee/Washington Post illustration; Demetrius Freeman/The Washington Post; Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post; Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post; Amanda Andrade-Rhoades for The Washington Post; Jose Luis Magana/AP; Alex Wong/Getty; Chip Somodevilla/Getty)

After Russia invaded Ukraine, Washington sent billions of dollars and loads of artillery to the Ukrainian military as the nation erupted into violence and chaos. Meanwhile, in the most peaceful and prosperous enclaves of Washington itself, the capital’s ruling class sent Ukrainian Ambassador Oksana Markarova a steady supply of their most precious resource: exclusive party invites.

In war, everyone has a role to play. Markarova’s job often means holding the line at galas and garden parties rather than battlefields. And she’s been reporting for duty all over town.

“I’ve seen her at like four or five parties,” says Ryan Williams, a longtime Republican operator, “and I don’t even live in D.C. anymore.”

“Everybody goes up to her and wants selfies, and I see that all the time,” says Steve Clemons, an editor-at-large and events guru for the news website Semafor, who has taken more than a half-dozen selfies of his own with the ambassador. “Somehow, she manages it.”

“She’s like Zelig,” says Sally Quinn, a preeminent Washington hostess who has held multiple dinners with Markarova. “She’s everywhere, everywhere, everywhere.”

French Ambassador Philippe Etienne, BlueCheck Ukraine co-founder Liev Schreiber and Ukrainian Ambassador Oksana Markarova attend the UnSanctioned Party in support of Ukraine at the French ambassador's residence in Washington on Jan. 27. (Paul Morigi/Getty Images)

A millionaire’s birthday party at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History with a performance by the American Pops Orchestra. A party for the opening of a new Bloomberg News office. A private dinner in a Georgetown mansion featuring lamb chops, pinot noir and John Kerry. A white-tie gala held by a semi-secret society of journalists that concluded with comedy sets by former vice president Mike Pence and Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Markarova joined first lady Jill Biden at the State of the Union. She joined the actor Liev Schreiber at a celebration at the French ambassador’s residence. She has been spotted at the Army-Navy football game. She threw out the first pitch on Opening Day last week at Nationals Park. She says she’s planning to attend the White House correspondents’ dinner later this month as a guest of USA Today.

Seeing and being seen is taken very seriously in Washington, where scoring a lot of invites can be a nourishing source of validation for the egos of the political class.

For Markarova, being in the mix — to use the local parlance — actually comes closer to being a matter of life and death. She is the face of her country in this all-important foreign capital at a time when Ukraine cannot afford to be anything but highly visible to influential Americans. That can mean whipsawing, mentally, between the fog of war and the din of polite company. It can mean hearing about people she knows dying — and then, moments later, walking into a room full of expectant strangers with a gracious smile.

“Sometimes it’s a little surreal,” the ambassador says.

She is sitting in a quiet drawing room at the Ukrainian Embassy in Georgetown, surrounded by shelves of intricately decorated eggs. On her blue blazer she wears a small angel pin in honor of Ukrainian children who have been kidnapped by Russia. Markarova describes herself as shy; if she had her way, she might turn down more invitations. Spending her evenings among the rich and powerful with open bars and canapés, while kids are snatched and parts of her country struggle to maintain electricity or running water, can be “difficult to bear,” she says.

Being a wartime diplomat was not the job the former finance minister envisioned when she began the job as ambassador just weeks before the conflict began. Between the time zone difference (Kyiv is seven hours ahead), the long business days and her nightlife rounds, Markarova is known, according to one of her colleagues in the embassy, as “the woman who never sleeps.” Not that she would ever complain about her posting. How could she? When her people back home call her, they “never talk about how difficult it is,” she says. “They just say, ‘Do what you need to do.’”

Markarova acknowledges applause as President Biden delivers his first State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress at the Capitol on March 1, 2022. (J. Scott Applewhite/AP) |

“It’s important to have her in everybody’s presence, because her being there says the country is resilient,” says Adrienne Arsht, the philanthropist whose birthday bash at the Smithsonian featured live music and a lavish buffet dinner as guests mingled among the dinosaur fossils. Markarova was there, hanging out in the rotunda near the life-size elephant statue. “She works all day and then goes out at night. That, too, is strength.” (Her birthday-gift game was also strong: Arsht says the ambassador gave her “a beautiful necklace by a Ukrainian artist.”) Before events, Markarova will ask hosts for the guest list, and sometimes for advice about the important people to speak with. In practice, however, she rarely needs to seek anyone out. Lines of people form around her, often from the moment she arrives. They ask her how they can help, they ask for updates on the war effort, they ask her about her family (she’s a mother of four) and ask her how she’s doing. That’s the hardest question to answer. |

She’ll talk to as many people as she can, sometimes give a speech, but rarely stays long. She keeps her phone out at dinners, a faux pas for which she has a good excuse: Ukraine remains under martial law, so she needs to be available 24/7. “Usually I will not stay for the fun, fun part,” Markarova says about the parties she attends. “Because I cannot forget that there is a war.”

From left, CNN reporter Eva McKend, BlueCheck Ukraine co-founder Liev Schreiber, Oksana Markarova and CNN anchor and senior political correspondent Abby Phillip attend the UnSanctioned Party in support of Ukraine at the French ambassador's residence in Washington on Jan. 27. (Paul Morigi/Getty Images)

In most cities, going out to a party is supposed to be a good time. But that’s not always the case in Washington, where just as often it’s referred to as “a working evening.”

“Usually there’s a purpose to these things; it’s not just mindless mingling,” said Marie Yovanovitch, the former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine. Every party can come with an objective: information gathering, informal negotiating, relationship-building.

“When you are breaking bread with somebody, it’s a slightly different way to get to know people and build confidence and trust,” Yovanovitch says. “I’ll tell you personally, as an introvert: It’s hard — but important — work.”

Markarova is good at it, according to people who talked to The Washington Post about her social skills: whip-smart, charming, a good listener and powerful storyteller. Good thing, because “if the ambassador were someone far more narcissistic or self-absorbed or shy, this would be a disaster for Ukraine,” says Clemons.

At parties, Markarova is “forthcoming,” he says, but not “gushing” or “flamboyant.” She does not “overshare,” she makes people “feel good” when they talk to her. Importantly, she shows a “reluctance” to be at the party in the first place.

Sean Doolittle of the Washington Nationals greets Markarova after she threw out the ceremonial first pitch during Opening Day at Nationals Park. (Jonathan Newton/The Washington Post)

“Combined,” Clemons says, “that makes her a prized guest.”

“She has a sort of mischievous sense of humor,” Quinn adds. “She likes to joke and tease and all that kind of thing, but she is also incredibly serious. When she talks about war, it is very dramatic, as you can imagine.”

Quinn — a longtime Washington Post writer and widow of former editor Ben Bradlee — has had Markarova over to her house in Georgetown for at least two dinners. At the most recent, held last month, the ambassador kept rapt an audience that included deputy national security adviser Jonathan Finer and Sen. Mark R. Warner (D-Va.) with her stories about the struggle and perseverance of Ukrainians — all while a team of men in ties made sure no one’s wine glass ran low.

“I asked her, ‘How does it feel to be here in Georgetown at this table when you hail from a country covered in a blanket of sadness and death?’” one guest said. In response, the ambassador was diplomatic: She spoke about what was going on in Ukraine and left Georgetown out of it.

Georgetown doesn’t like to be left out of anything, which is why Markarova is such a hot guest right now. “Everyone wants to be associated with Ukraine,” said Mark Leibovich, a journalist for the Atlantic (and another former Post writer) who has spent decades gawking at the customs and characters of Washington.

“It gives the parties a high-minded quality,” Leibovich says. “It allows them to have a cause bigger than their shrimp trays.”

Parties in Washington are often thrown under the auspices of helping out with some hot cause or another — a humanitarian disaster, or a horrible disease. In his 2013 book, “This Town,” Leibovich introduced readers to Tammy Haddad, “a veteran cable producer who repurposed herself in recent years as a professional party host.” Haddad began throwing fundraisers for epilepsy research alongside Susan and David Axelrod, Leibovich wrote, because it was a cause near and dear to the White House power couple.

Now the hot cause is Ukraine, the underdog that has made good use of all that American weaponry to hold the line.

“You gotta love Ukraine,” Leibovich said. “The same way you gotta hate cancer.”

Haddad (who — let’s get it out of the way — has also worked for The Post, as a consultant) and others involved in the Washington party industrial complex make a compelling case that a lot of good can come from these parties. She has organized multiple events where Markarova was a featured guest, including a blowout at the French ambassador’s home celebrating a group of people who had been sanctioned by Russia. That event raised money for BlueCheck Ukraine, an organization that helps support Ukrainian NGOs and aid initiatives.

Markarova at the UnSanctioned Party in support of Ukraine at the French ambassador's residence in Washington on Jan. 27. (Paul Morigi/Getty Images)

Of course, one of the best ways to get people to open their wallets for a cause is to throw a good party. And the best way to throw a good party is to bring in an electric guest.

“Is there such a thing as a war rock star?” Haddad says. “I don’t know. I don’t think there really is. But if there was, she would be the person.”

Markarova may not feel like any kind of rock star, but she does her best to be the kind of guest that continues to get invited to exclusive events.

“If you want to explain to people and engage people who are not at war, you have to engage them in a way they understand,” the ambassador says. “So, if I were to go in military camouflage everywhere and say, ‘It’s war! It’s war! Wake up!’ people would say I’m, you know, a crazy person.”

You can’t cry at a party, either. It might make people uncomfortable. It might make people think she’s weak, when the moment requires strength. So, she smiles.

“But that doesn’t mean I didn’t cry after,” she says.

Markarova does enjoy parts of being a popular party guest. She says she’s made good friends. (“It’s very difficult to find friends as an adult,” she says, “but this is one of those very rare professions where you meet remarkable people.”) She loved the Gridiron dinner, where journalists and politicians dress in fancy clothing and make each other laugh. (“Singing and joking and food? Sounds like a Ukrainian party.”) Exclusivity aside, there’s something familiar about these gatherings. “You know, people in Ukraine also like to — as they always say — grow food, raise children and go to parties,” Markarova says. “But, unfortunately, we have to put that all aside and fight.”

The ambassador says she believes every single event she’s attended has been important. Social gatherings are not inherently frivolous, least of all here in Washington. She has proof of this right in her very own embassy.

“Did you know the District of Columbia was created in a room in this building?” Markarova says wrapping up the interview. “Oh, I have to show you.”

She takes an elevator to the first floor of the embassy and walks into a room with a painting of George Washington and a plaque on the wall. It was right here in 1791, according to the plaque, that President George Washington and a group of landowning dignitaries discussed and settled upon the city’s boundaries.

It all happened, Markarova points out, at a dinner party.

Markarova arrives to speak at an event unveiling a photography exhibit about the war in Ukraine on Capitol Hill on April 28, 2022. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)