Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

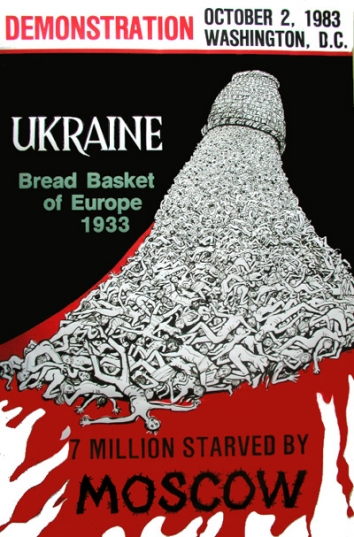

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

Former PM Lazarenko fights to keep his offshore millions from US govt seizure- over $250 million

Pavlo Lazarenko, felon and former prime minister of Ukraine, is battling the United States for $250 million held offshore and for political asylum.

Pavlo Lazarenko, felon and former prime minister of Ukraine, is battling the United States for $250 million held offshore and for political asylum.

By Leslie Wayne, New York Times, NY, NY,

Wed, July 6, 2016

On any given day, Pavlo Lazarenko looks like an ordinary stay-at-home dad, shuttling his three small children to school and waiting for his young wife to return home from work. Perhaps he’ll run an errand or two.

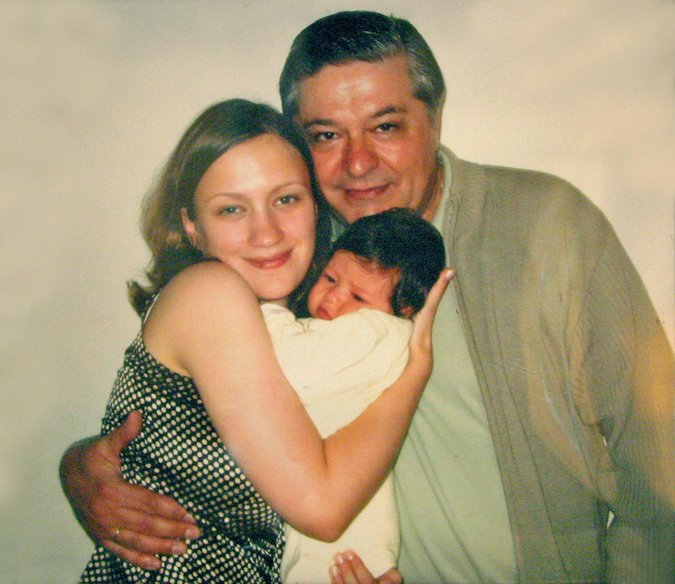

Photo: Pavlo Lazarenko, left, the former prime minister of Ukraine, with his son, Olexander Lazarenko, in 2004. Credit Paul Sakuma/Associated Press

But Mr. Lazarenko, it turns out, is a world-class kleptocrat hiding in plain sight in suburban America. He is the former prime minister of Ukraine, where he was accused of siphoning hundreds of millions of dollars for his personal use. Transparency International named him one of the world’s 10 most corrupt officials.

He is wanted in his native Ukraine. He has been convicted of money laundering in the United States and, in absentia, in Switzerland. Moreover, his name recently surfaced in the leaked secret documents known as the Panama Papers in a long-running corruption case involving the alleged theft of Ukraine’s natural gas resources for himself and his political allies.

Even more, Mr. Lazarenko is waging two fierce battles with the United States government. One is over $250 million in offshore accounts in Guernsey, Switzerland, and elsewhere that the government claims are the fruits of Mr. Lazarenko’s “fraud, extortion, bribery, misappropriation and embezzlement.” The other is his effort to remain in the United States, where he has been seeking political asylum since arriving in 1999.

So far, Mr. Lazarenko is more than holding his own. With an army of lawyers, he has been able to stave off deportation, even though he served time in federal prison on a felony money-laundering conviction a few years ago. The battle over returning his riches to Ukraine has been tied up in courts for years, and will be for years to come.

He is in legal limbo — not a citizen, not a visa holder — and yet he is able to operate freely from his California home. What the Lazarenko case demonstrates is just how difficult it is for the United States government to go after what it says are the ill-gotten gains of those with outsize power and influence.

“This shows you who outguns whom in the battle against corruption,” said Kenneth Hurwitz, an anticorruption officer at the Open Society Justice Initiative. “He’s got the resources, and a lot of money is at stake.”

In response to questions, Mr. Lazarenko’s attorney, Daniel Horowitz, declined to comment or make Mr. Lazarenko available.

These days, Mr. Lazarenko, 63, lives in Marin County, across the Golden Gate Bridge from San Francisco, with his second wife and a new family.

Lazarenko and his new family

While his current home is comfortable, it is a far cry from the 18,000-square-foot Novato mansion — one of the largest in California — he bought before fleeing Ukraine in 1999 just one step ahead of the prosecutors.

That Novato mansion, also in Marin County, was seized by the federal government in 2013 after Mr. Lazarenko became only the second head of state — Manuel Noriega, the Panamanian dictator, was the first — to be convicted in American courts of money laundering. In a sweeping 53-count indictment in 2000, the government identified $114 million that Mr. Lazarenko laundered through financial institutions in the United States. He was sent to prison in 2009.

“I’d be disappointed if the United States granted him asylum,” said Daria Kaleniuk, executive director of the Anticorruption Action Center in Kiev. “It’s quite cynical of him to apply for U.S. asylum at the same time he is fighting the U.S. for $250 million that the U.S. has frozen and is trying to repatriate to the Ukraine government.”

Moreover, Ms. Kaleniuk said, “U.S. taxpayers have paid a lot to fight cases against him in Washington and California.”

In America, the strange saga of Pavlo Lazarenko began as his plane touched down at John F. Kennedy Airport in February 1999. He was fleeing accusations that he had ordered the murder of a political rival; he had barely escaped an assassination attempt. He left days before Ukrainian prosecutors were to charge him with embezzling government resources (they set the charges aside when he fled the country). He was wanted by the Swiss government as well.

By all accounts, he arrived expecting the life of an offshore oligarch. He already had a Panamanian passport. A series of hidden shells funneled money to buy his $6.75 million mansion in Novato. The sprawling estate, once occupied by the Hollywood star Eddie Murphy, featured two helipads, multiple swimming pools, a barn-size ballroom and gold-plated door knobs. Waiting for him were his first wife and their three children, already in local schools.

Also waiting was the F.B.I., which had him on a watch list. He was whisked to a Queens jail and never spent a night in his California palace. A year later, he was indicted on charges of money laundering. In 2004, he was found guilty and, after appeals, entered federal prison in 2009. After leaving prison in November 2012, he was in an Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center, although I.C.E. declined to say when it released him.

While Mr. Lazarenko was in prison, a case brought by the United States government in 2004 to seize his offshore assets limped along. Over time, the government pinpointed money Mr. Lazarenko had stashed in Guernsey, Antigua, Switzerland, Liechtenstein and Lithuania. It fended off other claimants to the money and obtained a freeze order preventing Mr. Lazarenko from gaining access to it. But the case is so complicated, involving voluminous discovery in many countries, that it is not expected to go to trial until 2018.

“This case takes the cake in every category,” said David B. Smith, an asset forfeiture attorney representing Mr. Lazarenko. “It’s the largest, longest-running and most complex case. It has the most discovery and involves governments all over the world. Motions alone fill 10 volumes. Few cases go on for 13 or 14 years. It’s staggering.”

More recently, Mr. Lazarenko’s name surfaced in the Panama Papers. Documents obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists show that Mr. Lazarenko used many tricks of the offshore trade: shell companies, British Virgin Islands addresses and the services of Mossack Fonseca, the law firm at the heart of the leaked documents.

The Panama Papers include search warrants issued in 1998 by the British Virgin Islands for all Mossack files related to three companies connected to Mr. Lazarenko; Yulia Tymoshenko, who later became Ukraine’s first woman prime minister; and her husband. The warrants allowed for B.V.I. officers to “enter the said premises, by force, and breaking of doors, if necessary” to get the documents.

One of the companies named in the search warrants — Bassington Ltd. — was a B.V.I. shell set up by Mossack to hold the shares and be the parent of United Energy Systems of Ukraine, which controlled Ukraine’s natural gas supply. Mr. Lazarenko and Ms. Tymoshenko were political allies as well as partners in United Energy, which the United States government said allowed millions of dollars to flow to Mr. Lazarenko and his associates. Much of that money is now in the offshore accounts that Mr. Lazarenko and the government are fighting over.

The Mossack files also provide details of a key business relationship between Mr. Lazarenko and his closest Ukrainian crony that was central to the government’s money-laundering case. Mr. Lazarenko was co-owner, with the Ukrainian businessman Peter Kiritchenko, of a B.V.I. company, Bainfield Company Ltd., that the United States government said was used to “conceal and disguise” money “corruptly and fraudulently” paid to Mr. Lazarenko.

The two men had a longstanding arrangement in which Mr. Kiritchenko, who named Mr. Lazarenko as his child’s godfather and vacationed with his family, sent 50 percent of the profits from what the F.B.I. called “myriad criminal schemes” in Ukraine to Mr. Lazarenko through Bainfield. Mr. Kiritchenko later fled to the United States and became a key witness against Mr. Lazarenko, helping send him to prison.

Mr. Lazarenko’s lawyer, Mr. Horowitz, declined to comment. In court filings, he likened Mr. Lazarenko to Jean Valjean, the persecuted but ethical hero of Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables” who is hunted by an obsessed police inspector. The American government, he said, approached Mr. Lazarenko with “the intensity usually reserved for drug kingpins, child pornographers or other highly dangerous individuals.”

Mr. Horowitz, a celebrity defense lawyer and frequent television commentator, traveled the world gathering evidence to defend Mr. Lazarenko. His website says Mr. Lazarenko’s “pro-Western views and his belief in a free economy angered the dictators of Ukraine and led to the back door deal that led to his arrest. Ukraine has never recovered.”

During Mr. Lazarenko’s legal battles, his personal life changed greatly. He is now married to Oksana Tsykova, who was his translator at his 2004 trial and was carrying his child — the first of three — at the time. Ms. Tsykova owns their current Marin County home, valued at $1.8 million, in a trust in her name. She is also a lawyer in Mr. Horowitz’s firm.

It is doubtful that he would return to Ukraine. The prosecutor’s office has said Mr. Lazarenko would be arrested and has stockpiled evidence against him.

At the moment, Mr. Lazarenko is pleading poverty. In court filings, he says he has no income, owes a former lawyer $100,000 and relies solely on his wife’s salary. Mr. Lazarenko also says, in court filings, that he lacks work authorization and is unemployed. Even more, by all accounts, he does not speak much English and relies on a translator.

Not everyone buys Mr. Lazarenko’s story. Martha Boersch, the former lead prosecutor on the money-laundering case, said, “He’s got a lot of money left and hidden away.”

One of the big questions is why Mr. Lazarenko, a felon, has not been deported.

“It strikes me as bizarre,” said Mr. Hurwitz, of the Open Society. “You’ve got 12-year-old kids from Central America being kicked out and he’s still here.”

In general, a criminal conviction does not prohibit asylum seekers from pleading before an immigration court. Marc Van Der Hout, Mr. Lazarenko’s former immigration lawyer, declined to comment on the case, but said that it was not unusual for asylum cases to drag on for years. As policy, I.C.E. does not comment on individual cases.

The fight over Mr. Lazarenko’s offshore assets is heating up. He recently added Blank Rome, one of the nation’s largest law firms, to his team, which claims the government lacks jurisdiction to seize his offshore millions since they were not deposited in the United States but only passed through in brief electronic transfers.

“The money was in the United States for a matter of seconds,” said Mr. Smith, of Smith & Zimmerman, which is working with Blank Rome. “That’s not enough to show that it had any connection to the U.S.”

Some experts say Mr. Lazarenko is making headway. “This is such a politically sensitive case,” said Linda J. Candler, a California lawyer who represents the Anticorruption Action Center in Kiev, which wants the money repatriated to Ukraine. “Lazarenko is fighting this vigorously. He’s got good counsel and they are making solid arguments.”

In the end, perhaps the best comparison with Mr. Lazarenko’s case is the infamous Jarndyce and Jarndyce in Charles Dickens’s “Bleak House.”

“This is like something out of a 19th-century novel,” said Mr. Smith. “It seems like this case will go on forever.”

Correction: July 6, 2016

Because of an editing error, an earlier version of this article misspelled in one instance the name of the city where Mr. Lazarenko’s former mansion is. It is Novato, not Navato.