Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

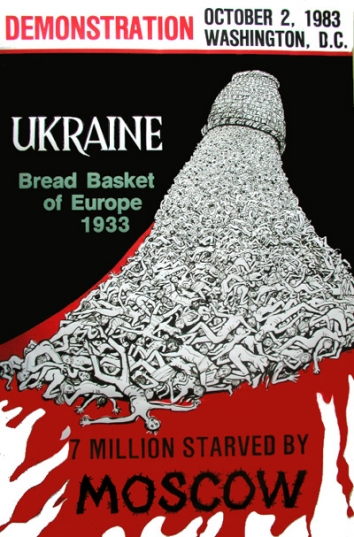

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

SETTING COSMIC AMBITIONS FOR UKRAINE

.jpg) FIREFLY, Texas, United States,

FIREFLY, Texas, United States,

Mar 24, Tue, 2020

.png) For a man with big space dreams, serial entrepreneur Max Polyakov is unusually focused on Earth. The co-founder of U.S. startup Firefly Aerospace is in no rush to get to Mars. And launching an interstellar space station? Let that remain the stuff of fantasy films.

For a man with big space dreams, serial entrepreneur Max Polyakov is unusually focused on Earth. The co-founder of U.S. startup Firefly Aerospace is in no rush to get to Mars. And launching an interstellar space station? Let that remain the stuff of fantasy films.

“We see Earth as a resource that needs to be saved for humanity, first and foremost,” he says. “That’s our only chance for survival.” And satellites with practical applications — vaulted into orbit atop Firefly-made rockets, of course — will be crucial to that effort, he adds.

But Earth isn’t the only place Polyakov is hoping to rescue. The 42-year-old native Ukrainian is looking to his troubled homeland for technical help: Starting with a research-and-development center in Dnipro, a historically rich hub of rocketry, he’s also hoping to preserve what’s left of the country’s Soviet-era prowess in aerospace. That won’t be easy: The end of the communist superstate in 1991 meant a collapse in both state funding and demand for the kind of rockets that kept the Soviet military competitive during the Cold War.

Toss in the corruption and political volatility that’s plagued Ukraine since independence, and things just haven’t been the same. But a deep-seated intellectual legacy, anchored in decades of top-quality scientific and technical education, fuels hope that Ukraine can soar again — this time, as an independent country. “We’re trying to catch the very last train before it departs, so to speak,” Polyakov says.

WHAT WE’RE DOING IN UKRAINE IS PRESERVING KNOWLEDGE.

MAXIM POLYAKOV

A lightning-fast talker with a rugby player’s build and a salesman’s disposition, Polyakov is no stranger to launching profitable projects. Before pulling Firefly back from bankruptcy several years ago through his Silicon Valley-based investment firm, Noosphere Ventures, he founded and sold an array of startups in fields like ad tech, online dating and mobile gaming. “He doesn’t enter into projects until he knows his strengths and weaknesses,” says Noosphere co-founder and chairman Michael Ryabokon.

A recent Snopes investigation linked Polyakov to a ring of “deceptive dating companies,” but a Noosphere spokesman called it a “manipulation” orchestrated by early Firefly investors suing him and co-founder Tom Markusic for allegedly driving the company into bankruptcy and forcing them out.

Now Polyakov, a jovial father of four, is hoping to shake up the burgeoning private space industry with Texas-based Firefly by offering reliable and competitively priced delivery systems for satellites. Its first major test comes some time this year, when a 2,200-pound capacity Alpha rocket will send up 26 satellites for a variety of clients, including university research programs and nonprofits, as part of its Dedicated Research and Education Accelerator Mission (DREAM). Already, demand appears strong, with a current order pipeline of up to $2 billion. At Firefly’s Austin facility, where it employs around 250 people, the company is able to crank out rockets at a rate of eight per year — and hoping to boost that capacity to 24 per year once it builds another factory on Florida’s Space Coast.

But its presence in southeastern Ukraine’s Dnipro, an industrial powerhouse of around 1 million, is equally important. There, some 150 experts are developing the technology that could help launch Firefly to the forefront of the market. It’s the foundation of what Polyakov hopes will be an ever-growing cluster of rich generational know-how, just like the old days. By allowing his employees to live and work “in the cocoon in which they were born and raised,” rather than taking their talents abroad, it boosts their sense of purpose, he adds.

It’s part of a broader company investment in Ukrainian intellect, which is also marked by Noosphere’s partnership with two top-flight universities, the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute and Dnipro National University. That union aims to foster student interest in space. “What we’re doing in Ukraine is preserving knowledge,” says Polyakov.

Firefly’s injection in Dnipro, the former beating heart of the Soviet Union’s aerospace industry, couldn’t have come at a better time. Together, the Yuzhmash machine-building plant and its accompanying design bureau, Yuzhnoe, cranked out hundreds of missiles and satellites for the Soviet space and defense programs, lending the sector and its workers an elite status. While work there hasn’t completely ground to a halt, the complex has fallen on hard times since Ukraine gained independence — a reflection of the country’s broader financial misfortunes since the early ’90s.

Firefly’s Alpha rocket.

Yuzhmash facilities are languishing in disrepair while management hasn’t paid the staff on time. The fact that it’s state-owned, like the rest of the aerospace sector, harms competition and deters otherwise eager foreign investors. “It’s discouraging both for them and our state companies,” says Anastasiya Bolkhovitinova, a Kyiv-based lawyer who specializes in the aerospace industry. Ukraine’s ongoing war with Russia, once its key partner and customer, has been particularly bad for business.

But a new law loosens the state’s grip on the sector by allowing private companies and individuals to pursue commercial aerospace activities with state companies. Even before that law was enacted in January, Firefly had already stepped up its partnership with Yuzhmash, having signed a $15 million deal last year for the plant to produce 100 combustion chambers, among other rocket parts. If all parties play their cards right, that could be the beginning of game-changing cooperation for both Ukraine and the private space transportation sector. President Volodymyr Zelenskiy himself has publicly emphasized the importance of the move.

But Polyakov is well aware that nothing’s guaranteed in the rocket business. “Even if a submarine or aircraft carrier fails, you can still pull them back to port and see what went wrong,” he says. Rocketry, on the other hand, is all or nothing — that is, you won’t know you’ve screwed up until your very expensive product blows up in your face. Literally.

Still, that seems worth the risk for Polyakov — and Ukraine’s aerospace dreams may well depend on it.