Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

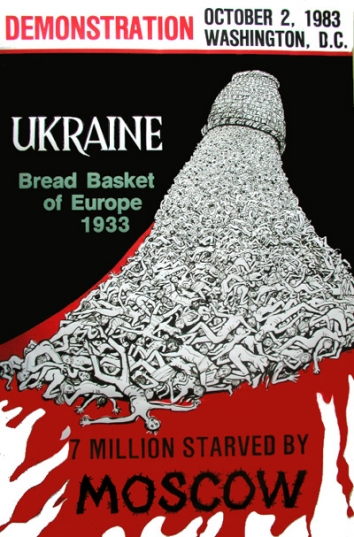

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

Toll of the Bells: The forgotten history of nationalism, oppression, and murder behind a Christmas classic

By Lydia Tomkiw, Thu, Dec 19, 2019, Slate, Wash, D.C.

The Ukrainian National Chorus in Buenos Aires in 1923. Courtesy of Oseredok, the Ukrainian Cultural and Educational Centre, Winnipeg

A group of men and women in traditional embroidered dress took the stage at Carnegie Hall on Oct. 5, 1922, for a performance that the New York Tribune dubbed “a marvel of technical skill.” The New York Times called the music they made “simply spontaneous in origin and artistically harmonized.” The New York Herald described the costume-clad singers as expressing “a profound unanimity of feeling that aroused genuine emotion among the listeners.” The audience that cheered for encores and threw flowers on the stage didn’t know it at the time, but they had just heard what would eventually become one of the world’s most beloved and recognized Christmas songs: “Carol of the Bells.”

Onstage was the Ukrainian National Chorus conducted by Alexander Koshetz. At the end of Part 1 of the program at Carnegie Hall, they performed composer Mykola Leontovych’s arrangement of a traditional Ukrainian song the playbill called “Shtshedryk.” The audience likely also did not know that just over a year before the New York premiere, Leontovych had been assassinated by the Cheka—the Bolshevik secret police.

The song’s journey onto the world’s stage and its transformation into an American Christmas classic is a tale of musical inspiration, nationalism, and political violence. At its center is a beautiful, haunting melody that has captivated audiences for over a hundred years and spawned countless versions.

“There are many people who don’t know it’s Ukrainian, I think the majority,” says Larisa Ivchenko, head of the music department at the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine in Kyiv. When I visited in 2017, Ivchenko had spread out photographs, sheet music, and program tour brochures that are part of the archive’s collection. A photo dated 1919 from Prague shows the chorus, then known as the Ukrainian Republican Kapelle. In the photograph, a group of almost 80 people are posed without smiling—the men wearing black suits and the women in white dresses.

The chorus had just set off on a world tour that would take them across 10 countries in Europe over three years and then to North America where they’d sing widely across the U.S., including small towns far from the glitz of Carnegie Hall. In the U.S. alone, they visited 36 states and 115 cities, according to a count by Tina Peresunko, a researcher at the Ukrainian Institute of Archeography and Source Studies. “Shchedryk,” as it is more accurately spelled, was the standout “hit” from the chorus’ repertoire according to concert reviews and the conductor Koshetz’s own reaction recorded in his memoirs, she adds.

“There are many people who don’t know it’s Ukrainian, I think the majority.”— Larisa Ivchenko

“When they came over to America it would have been sort of this curiosity of interesting, exotic songs,” says Marika Kuzma, a professor emerita in the Department of Music at the University of California–Berkeley.

An article in the New York Times heralded the group’s arrival by boat in late September, “50 RUSSIAN SINGERS LAND IN GAY DRESS.” While the article praised the singers, it also reflected the attitudes of the time. The Times performance review described the singers in “motley costumes” with “gaudy” headdresses singing “primitive peasant airs” of the “six provinces of ‘Little’ or Southern Russia.” Conflation and confusion between Russia and Ukraine irritated the Ukrainian chorus who would correct reporters, according to archival material collected by Peresunko.

The review concluded that the music of “Ukrainia” did suggest “the colossal wealth of youthful and untouched vitality which had tided over centuries of the most tragic history in the world.”

The Ukrainian Republican Kapelle with conductor Alexander Koshetz in Prague in 1919.

Courtesy of the Central State Archives of Higher Authorities and Administration of Ukraine (Kyiv).

During her 25 years directing choirs, Kuzma taught “Shchedryk” to her students at Berkeley. “It’s curious to me how it really morphed into this different context and how much people don’t know what the carol is about,” she says.

Dating back to pagan times, Ukrainians sung shchedrivky, songs welcoming the start of the new year with hundreds of versions, including ones devoted to bears and bees, says Valentyna Kuzyk, a senior researcher at the Rylskyi Institute of Art, Folklore Studies and Ethnology in Ukraine.

Leontovych drew inspiration from Ukrainian folk songs and melodies as a composer, choral conductor, and also a teacher. He was born in 1877 to a religious family in the Podilia region of southwestern Ukraine and completed studies at a theological seminary. His musical career would take him across the region he called home as well as to Kyiv, St. Petersburg, and Moscow. Besides “Shchedryk,” he produced over 150 other classic works for choirs during a career that was cut short.

Leontovych worked for several years on his arrangement and orchestration of “Shchedryk.” It’s likely the song’s famous four-note tune started from a version he would have heard during his childhood in Podilia, Kuzyk says. Leontovych sent his arrangement to choir conductor Koshetz in August 1916 and several months later, a choir in Kyiv premiered the song.

The Ukrainian version has nothing to do with bells or Christmas. The lyrics tell the tale of a swallow summoning the master of the house to look at his livestock and the bounty the coming spring season will bring as well as to look at his beautiful dark-eyebrowed wife. In pre-Christian times, the coming of the new year and spring were celebrated in March.

“Shchedryk” came to prominence in its current version during a tumultuous and bloody period. The Romanov dynasty, which then ruled a vast part of Ukraine, fell in March 1917 and for a brief moment, an independent Ukrainian state—the Ukrainian People’s Republic—was declared in 1918. Symon Petliura, the president, saw the value in promoting Ukrainian culture around the world to gain support for his fledgling state. And it was in this window that the chorus, under Koshetz’s leadership, embarked on its tour.

While touring in Europe with the support of the Ukrainian People’s Republic, the choir would pass out brochures with the symbols of their new country and sing what is today Ukraine’s national anthem, according to Persesunko’s research.

“Shchedryk” came to prominence in its current version during a tumultuous and bloody period.

By 1921, the short-lived People’s Republic had fallen. “During the interwar period (1918–1939), the Ukrainians emerged as the largest nation in Europe with an unresolved national question,” writes Harvard historian Serhii Plokhy in The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. “Ukraine lacked a state of its own, and four European states had divided its territories: Bolshevik Russia, Poland, Romania, and Czechoslovakia.” An independent Ukraine wouldn’t reemerge until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The choir left Ukraine during a period of great turmoil. The Cheka, which later evolved into the KGB, killed thousands in an effort to build and consolidate Bolshevik rule in a period (1918–1922) that became known as the Red Terror. The head of the Cheka, Felix Dzerzhinsky, brought 1,400 men into Ukraine to deal with unrest. In the first half of 1921, they killed 444 rural rebel leaders in Ukraine alone, according to Anne Applebaum’s Red Famine. Ukraine’s intellectual class and religious leaders were also targets.

This included the composer of “Shchedryk.” On the night of Jan. 23, 1921, in the village of Markivka, Leontovych was shot by Afanasy Grishchenko, who is described as an “agent” in a Soviet document. Leontovych had been staying at his father’s house when Grishchenko asked for shelter for the night. He shot Mykola Leontovych with a rifle, according to the archival document, and a few days later also shot and wounded a policeman.

While there has been speculation that the incident may have been a robbery, Kuzyk says, “This was a political matter.” She believes that Leontovych was targeted because of his association with the recently established Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church.

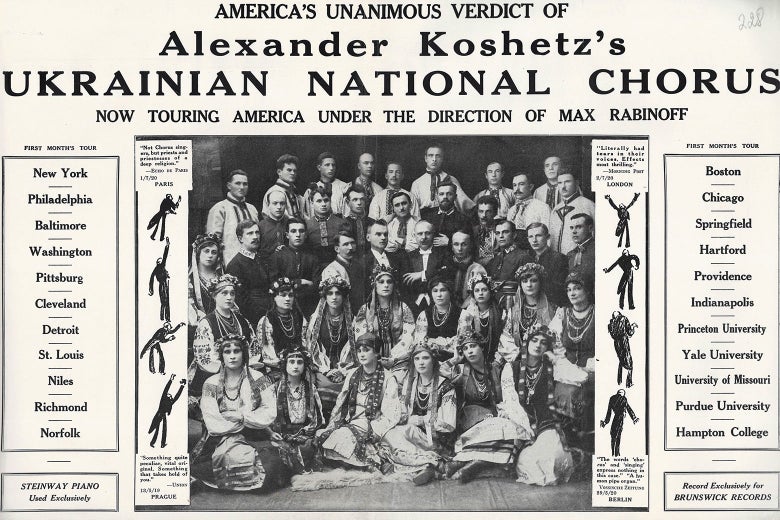

A playbill of the Ukrainian National Chorus’ concert tour of U.S. cities and universities in October–December 1922.

Courtesy of the Central State Archives of Higher Authorities and Administration of Ukraine (Kyiv).

While their country was in turmoil, the chorus was still touring. With support from the now-defunct Ukrainian People’s Republic drying up, the tour took on a more commercial flavor. Over a year after Leontovych’s death, the choir came to New York under the management of Max Rabinoff, a Russian-born impresario who worked in the music and business worlds and had seen the choir perform in five countries.

According to legend, in the audience that night at Carnegie Hall was a man named Peter Wilhousky—who would go on to write the famous English lyrics about “sweet silver bells” ringing “ding dong ding dong.” Wilhousky was a classically trained choral director and music administrator in New York public schools.

Born in Passaic, New Jersey, Wilhousky attended the Russian Cathedral Choir School in New York as a child along with his siblings. He studied at Juilliard and later spent several years teaching there, according to archivist Jeni Farah.

“He came from a family with an intense interest in music,” reads Wilhousky’s 1978 obituary in the New York Times.

Wilhousky’s family was typical of the early parishioners at Saints Peter and Paul Russian Orthodox Cathedral in Passaic, having immigrated from what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire and is today part of northeastern Slovakia, said the Rev. Stephen Kaznica, a priest at the church. His family was of Carpatho-Rusyn heritage, and it was likely that Wilhousky would have spoken Rusyn—a regional language from Western Ukraine—at home and also learned Russian at school, Kaznica said.

Wilhousky worked with Italian composer Arturo Toscanini for NBC Symphony broadcasts; his arrangement of “Battle Hymn of the Republic” remains another of his most famous works. He also left a mark on his students, “He was one of the finest choral conductors in America, yet he chose to spend every Saturday morning with high-school kids,” wrote Stephen Jay Gould, a professor of geology at Harvard, in a 1988 New York Times piece recalling his time under Wilhousky’s direction.

Archivists and historians haven’t been able to substantiate whether or not Wilhousky was in the audience to hear the Ukrainian National Chorus at Carnegie Hall. It’s possible he also heard a recording made by the chorus for Brunswick Records that same year. His own version, with new lyrics and a new title—“Carol of the Bells”—was published and copyrighted in 1936 by Carl Fischer Music in New York.

“It just took off, it was incredible,” said Vera Forbes, Wilhousky’s niece, by phone in 2017 of her uncle’s version. Forbes, who herself was in show business and sang for many years, died in 2018.

Forbes recalled hearing the original “Shchedryk” sung when she was a child. Her memories of Christmastime include all the churches ringing their bells at midnight—something that may have inspired her uncle. Wilhousky had “a high voice, a fantastic voice,” Forbes said.

Forbes knew the song had reached commercial prominence when her husband called her to the television asking if a champagne ad was using her uncle’s song. “Uncle Peter is the guy who made ‘Carol of the Bells’ so popular,” she said.

“It’s used all the time. I can’t begin to tell you how many times it’s used,” said Jay Berger, manager for licensing and copyright at Carl Fischer Music/Theodore Presser Company. Christmas starts in July for Berger—with advertising companies deciding whether they will license “Carol of the Bells” for commercials and movie productions, he said.

“Carol of the Bells” is memorably used in Home Alone as Macaulay Culkin booby-traps his home. The Muppets tried their hand at singing it, too. It’s een in commercials for everything from André sparkling wine to Audi. In one memorable NBA promo from 2012, a lineup of basketball stars dribble the melody.

Other musicians have put their own touches on the tune from the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, to the Trans-Siberian Orchestra, and even a sultry sounding version by Destiny’s Child with Beyoncé. One of the most popular on YouTube, with over 149 million views, is a recent update by the a capella group Pentatonix. The artists singing these versions likely have little idea of the song’s tragic history.

There is still deep reverence for the original “Shchedryk” in Ukraine, Ivchenko said. While the song is being used in some commercials now, they are not Christmas ones, but for New Year’s. New versions are also being made in Ukraine, including a popular cartoon video by Ukrainian musician Oleg Skrypka and singer Tina Karol recording a popular video.

In recent years in Ukraine, there has been an effort to tell the story of the famous song. A museum dedicated to Leontovych’s life was updated in the town of Tulchyn where he spent his later years, and a festival celebrating the song took place there earlier this year.

While the Ukrainian chorus saw members come and go, those who finished the tour never returned to Ukraine and instead settled in the North America, Kuzyk says.

“You could be 5 years old or 95 years old. Everyone knows ‘Carol of the Bells,’ ” Berger says. “It has legs that last forever and forever and ever.”