Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

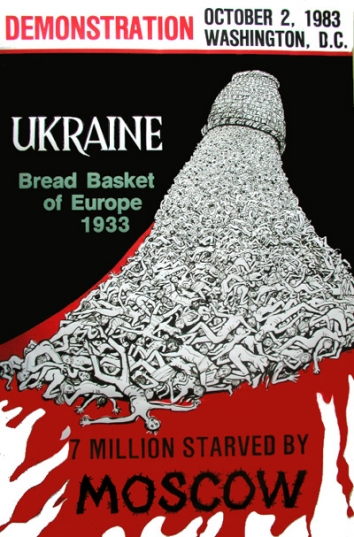

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

Traditionally Dyed Eggs Spring Into Action for Ukraine

The colorful folk art is a centuries-long custom

The colorful folk art is a centuries-long custom

by Jane Recker, Smithsonian Magazine

Wash, D.C., Thu, Apr 28, 2022

Pysanky have been a Ukrainian springtime tradition for generations. Creating the intricately decorated eggs requires patience and a steady hand.

Courtesy of Sarah Bachinger

For centuries, intricately decorated eggs—pysanky—have brightened spring in Ukraine. The traditional handcraft has endured for generations. But since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, the elaborate eggs feel even more important to many Ukrainians across the globe.

As the Washington Post’s Theresa Vargas reports, the colorful eggs are being used by people throughout the Ukrainian diaspora to raise humanitarian funds for the embattled nation.

The folk art tradition is thought to date to Ukraine’s pre-Christian era, when people began decorating eggshells to honor deities, pay homage to the return of sun and new life to the landscape, and welcome spring. The hollow eggs gradually took on their names from the word pysaty, or to write, due to the use of wax, scratching tools and paint on the shells. Colored with plant dyes and, later, synthetic ones, the eggs became an increasingly intricate way to celebrate the season.

Today, the most common way to decorate a pysanka involves a stylus, some beeswax and multiple dips in dye—reminiscent of using a white crayon to draw designs when dying Easter eggs.

At first, the art was associated with pagan beliefs and the passage of winter into spring. When Christianity came to Ukraine in the 9th and 10th centuries, the folk rituals were grafted on to Christian concepts of resurrection and spiritual renewal.

Pysanky are created by dripping hot bee wax onto eggs in various patterns, then dipping the waxed eggs in dye.

Courtesy of Sarah Bachinger

As Ukrainian scholar Volodymyr Hodys writes in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine, pysanky were connected with a variety of folk beliefs; they could “protect one from evil, cure illnesses, and defend homes from lightning and fire.” Today, Hodys continues, pysanky “[constitute] a source of new masterpieces of the decorative folk arts.”

For people like Round Lake, New York’s Sarah Bachinger, the eggs are still deeply symbolic. She tells NPR’s Anastasia Tsioulcas that the tradition has long been associated with resistance to Russian rule over Ukraine. Banned in the Soviet Union for their religious connotations, pysanky were brought to other parts of the world by Ukrainians who left their homes but held fiercely to their traditions. “The diaspora kept the tradition alive,” Bachinger tells Tsioulcas.

So is she: NPR reports on Pysanky for Peace, a group Bachinger founded to raise money for on-the-ground humanitarian assistance in Ukraine.

Bachinger isn’t alone. Per the Washington Post, other members of the Ukrainian diaspora are using homegrown pysanky workshops and Etsy egg sales to raise money, too.

Another extension of the egg’s symbolic meaning? Museum exhibitions. The Boston Globe’s Linda Greenstein reports that Bachinger, a museum professional, has created a traveling exhibition called “Pysanky for Peace.” On view through June 18 at the Wenham Museum in Wenham, Massachusetts, it features 70 eggs decorated by volunteers. Bachinger tells the Globe she’ll donate funds to Razom, a nonprofit that provides medical supplies to Ukraine.

“The Pysanka: A Symbol of Hope,” on view at New York’s Ukrainian Institute of America through August 24, is another take on the power of pysanky. Curated by Ukrainian artist and ethnographer Sofika Zielyk, the exhibition won’t just display eggs; it will invite people to contribute pysanky of their own.

“This installation is an ongoing, living, and evolving endeavor,” museum officials say in a statement. “As more pysanky continue to arrive — in person, and by mail from all over the world—the installation will grow in size and symbolic power.”

“Pysanky for Peace” is on view at the Wenham Museum in Wenham, Massachusetts through June 18.

“The Pysanka: A Symbol of Hope” is on view at New York’s Ukrainian Institute of America through August 24.

NOTE: Jane Recker has written for Washingtonian Magazine and the Chicago Sun-Times. She is a graduate of Northwestern University and holds degrees in journalism and opera.