Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

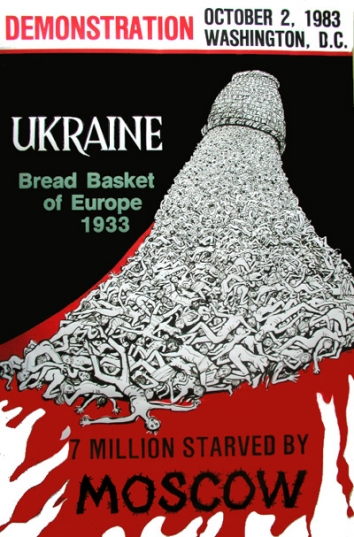

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

UKRAINE IN CONGRESS – A CENTURY OF U.S. CONGRESSIONAL SUPPORT FOR UKRAINE

.jpg) Orest Deychakiwsky, Former Policy Advisor, U.S. Helsinki Commission

Orest Deychakiwsky, Former Policy Advisor, U.S. Helsinki Commission

Published by U.S.-Ukraine Business Council (USUBC), Wash, D.C

Mon, March 16, 2020

- Introduction – Independence 1918 and 1991

It has sometimes been difficult for Ukraine to find international support but a strong argument can be made that Ukraine has had few better friends over the course of the last century than the United States Congress.

This was especially true in the decades leading up to the dissolution of the Soviet Union when Ukraine was a captive nation and a relative unknown in the United States. It is impossible to take a detailed, comprehensive look at Congress’ historic role in one article but I hope to at least give you a sense of the scope of Congressional engagement on Ukraine. Congressional efforts could be distilled to one word: freedom. It is the unifying theme. In this overview, I will try to briefly give you some sense of the what, when, where and why of Congressional activity vis-à-vis Ukraine.

A century ago, in 1917, a Congressman named James Hamill (D-NJ) introduced a Joint Resolution to proclaim a nationwide Ukrainian Day. And even though Ukraine was then a terra incognita in the United States, the resolution passed and President Wilson proclaimed April 27, 1917 as a day to collect moneys for the aid of the “stricken Ruthenians (Ukrainians).”

As a result of the collection, $85,000 – which is $1.75 million in today’s dollars -- was collected. Later, a Ukrainian information bureau was established in Rep. Hamill’s office, and he was active in trying to obtain U.S. recognition for Ukrainian independence, including through his subsequent December 1918 resolution on the eve of Versailles. But this measure was defeated, given U.S. policy at the time which decidedly did not support Ukrainian national aspirations. An excellent source on this is Myron Kuropas’ book Ukrainians in America.

Fast forward 72 years later to the Fall of 1991, when a resolution introduced by Helsinki Commission Chair Sen. Dennis DeConcini (D-AZ) and Commissioner Rep. Don Ritter (R-PA) calling for recognition of independence garnered significant support. It was adopted -- as an amendment to a larger piece of legislation -- despite a lack of support from the George H.W. Bush Administration. Although the first Bush Administration was not opposed to Ukraine’s independence per se – in contrast to Wilson --and certainly had an appreciation for Ukraine’s national aspirations, for various reasons it undertook a cautious approach.

In a little over a month, over ¼ of the Senate and 1/5 of the House joined the resolution as cosponsors -- which was no small feat and a tribute to various organizations and individuals in the Ukrainian-American community. In some respects, this resolution represented a culmination of longstanding efforts by the Ukrainian-American community and its many friends in the U.S. Congress prior to independence to assist the Ukrainian people in their aspirations for human rights, freedom and independence.

The Post World War II Era

So, what happened in Congress between 1918 and 1991? The inter-war period saw relatively little Congressional activity on Ukraine. A notable exception was the 1934 Congressional resolution on Stalin’s man-made Famine (Holodomor) introduced by Rep. Hamilton Fish (R-NY). Post-World War II saw an uptick. The Displaced Persons Act of 1948 and follow-on legislation – while not Ukraine-specific, did allow for the admission of some 80,000 post-war refugee Ukrainians living in Europe into the U.S. While previous Ukrainian emigrations had done much to establish the infrastructure of the Ukrainian-American community, this highly-politicized emigration and their American-born children gave the impetus for greater political activity, especially with respect to Congress.

During the late ‘40’s, through the 1960’s the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA) especially under its president, Dr. Lev Dobriansky, took the lead in Congressional activity on Ukraine. This included lobbying on behalf of a Ukrainian section within the Voice of America and presenting testimony in front of various congressional committees on issues concerning Ukraine.

Two pieces of legislation were of special significance. One was was the 1959 Captive Nations resolution, authored by Dobriansky who had many connections in both parties in Congress and who played a critical role in undermining the legitimacy of the Soviet Union. The other was the 1960 bill authorizing the erection of the Taras Shevchenko monument in Washington. The memorial dedication ceremony in 1964 saw the largest gathering of Ukrainian-Americans ever -- some 100,000. Both of these pieces of legislation and, in particular, the Captive Nations resolution, infuriated the Soviet government.

This was also a time when the January 22, 1918 independence of Ukraine was commemorated in Congress annually with events and numerous Congressional statements. To take just one illustrative example – I came upon a few January-February 1956 issues of The Ukrainian Weekly, reporting on the Independence Day activities, and they were filled with various Congressional statements, prayers for a free Ukraine in the Senate and House, and a report on the introduction of a resolution condemning Russian Communist oppression of Ukraine by Sen. Hubert Humphrey [D-MN], later vice-President of the U.S. Clearly, the focus during this period was on the national rights of Ukrainians.

The Peak of Pre-Independence Congressional Activity: 1975 - 1991

But it was the decade-and-a-half prior to independence, starting from late 1970’s that saw the most intensive period of Congressional activity on Ukraine. And it is here that there was somewhat of a shift in emphasis – from national rights to individual rights – although these, of course, were not mutually exclusive. A key reason for this transition was the newfound attention placed by the United States on the human rights provisions of the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, especially the plight of political prisoners including the Helsinki Monitors.

These courageous men and women called upon the Soviet government to live up to its freely undertaken Helsinki human rights commitments. The largest and most repressed of the five Soviet groups was the Ukrainian Helsinki Group. It members peacefully advocated not only for greater individual rights and freedoms, chronicling many individual violations, but also for greater cultural and linguistic freedoms as well as self-determination for Ukraine.

Not surprisingly, they were considered to be a particular threat to the Soviet regime and were harshly repressed. Four of them died in the Gulag as late as 1984-5, right before the era of glasnost/perestroika. Many members of Congress, often working closely with the Ukrainian-American community, vigorously rose to their defense. After their release, many became involved with Rukh, Ukraine’s movement for independence, including its co-founders Mykhailo Horyn and Vyacheslav Chornovil.

Institutionally, the creation of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (popularly known as the Helsinki Commission) shortly after the signing of the 1975 Helsinki Final Act whose mandate included pressing the Soviet government on human rights brought greater attention to Ukrainian issues.

This interest was manifested through numerous resolutions on behalf of individual Ukrainian political prisoners, hearings on human rights in Ukraine (occasionally with the participation of former political prisoners), frequent Congressional statements, press releases, Capitol Hill events and direct contacts with Soviet officials in Washington, D.C or at international conferences. The Congressional interest in human rights went beyond the Helsinki Commission and the issues went beyond the political prisoners or condemnations of human rights violations.

The’80’s saw Holodomor resolutions in connection with the 1983 fiftieth anniversary and very significantly, the creation of the Commission on the Ukraine Famine. This Commission did much to study and publicize this hitherto largely unknown genocide. Efforts of the Helsinki Commission and many others in Congress – especially members of the Ad Hoc Committee on the Baltics and Ukraine - focused on the plight of the suppressed Ukrainian Greek-Catholic Church calling for its legalization, especially in connection with a resolution on the Millennium of Christianity in Kyivan Rus-Ukraine.

Encouraged by the Ukrainian-American community, specifically the Committee to Commemorate the Millennium of Christianity of Rus-Ukraine, an unprecedently large number of Senators and Congressmen wrote individual letters to Soviet leader Gorbachev calling for the legalization of the Ukrainian-Greek Catholic Church. The 1986 Chornobyl disaster also brought considerable Congressional attention to Ukraine, with resolutions, hearings, statements and exhibits.

Sometimes too, Congressional efforts were geared toward our own government – for example, encouraging the State Department to raise individual cases of human rights abuse or related issues with the Soviets or calling for the establishment of a U.S. consulate in Kyiv (with the purpose of reducing Ukraine’s international isolation). There was also much Congressional unhappiness with the 1985 denial of U.S. asylum to Ukrainian seaman Miroslav Medvid, who jumped a Soviet ship near New Orleans.

Many of these activities were initiated or abetted by especially active lobbying campaigns not just by diaspora community organizations like the UCCA, the Ukrainian National Association (UNA) and Ukrainian National Women’s League of America (UNWLA) but also by numerous grass-roots groups of community activists who would pepper their Congressmen and Senators with phone calls, letters, face-to-face meetings, faxes. (This was before the rise of the Internet).

These groups included Americans for Human Rights in Ukraine (AHRU), Philadelphia Human Rights for Ukraine Committee, Smoloskyp organization in defense of human rights, and various ad-hoc human rights committees in cities with Ukrainian populations across the USA.

Also, key roles were played by offices such as UCCA’s Ukrainian National Information Service (UNIS), the World Congress of Free Ukrainians (WCFU) Human Rights bureau, and during the critical years of 1988-1995 – the lead-up to and immediate aftermath of independence -- the Ukrainian National Association’s (UNA’s) Washington office which employed professional staff, as well as Committees in Support of Rukh and Ukraine 2000 played vital roles.

As an example, Ukraine 2000’s international affairs director, Robert McConnell, testified or submitted testimony on Ukraine to more than 40 Congressional hearings in less than a two-year period. An essential role was also played by Ukrainian-American media, first and foremost, The Ukrainian Weekly which consistently informed the community and encouraged advocacy efforts.

The bottom line is that the Ukrainian-American community was especially engaged during those years. Without it there would not have been all the considerable activity that took place in Congress, especially in the pre-independence era. Keep in mind that prior to independence, many Americans were ignorant of Ukraine, often confusing Ukrainians with Russians or conflating Russia and the Soviet Union.

As mentioned earlier, before the restoration of its independence, with the exception of Congress, Ukraine was largely a terra-incognita on the overall political landscape in the U.S. The Executive Branch paid relatively little attention to Ukraine as it was essentially a colony and the focus, not surprisingly, was on the capital, Moscow, and not on the “periphery.” Nevertheless, Ukraine was not completely ignored and there were certainly people who were advocates for Ukraine within the Executive branch, including several Ukrainian-Americans. This relative lack of attention changed dramatically following independence and the establishment of formal relations with an independent Ukrainian state.

At that point, quite logically, the Executive Branch/ State Department, with the US Embassy in Kyiv, took the lead on Ukraine policy. Still, Congress has continued to be very active and supportive, on a bipartisan basis – both Republicans and Democrats. It is important to underscore that this bipartisanship on Ukraine existed before independence.

Post-Independence (1991-2013)

Since independence, we have seen legislation, hearings and briefings, direct meetings with Ukrainian legislators and officials, especially diplomats from the Ukrainian Embassy in Washington, and visits to Ukraine by Members of Congress. The drivers of most of the activity are the Helsinki Commission, Congressional Ukrainian Caucus, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and House Foreign Affairs committees. This included hearings on the political situation in Ukraine, sometimes with the participation of high-ranking Ukrainian officials; successful legislation authorizing the establishment of the Holodomor Memorial near the U.S. Capitol; Ukraine Permanent Normal Trade Relations (lifting restrictive Jackson-Vanik trade provisions); resolutions calling for Ukraine’s joining the NATO Membership Action Plan; and resolutions congratulating Ukraine for democratic successes.

There were many Congressional resolutions, statements and briefings in support of free and fair elections in Ukraine, on the Holodomor, Chornobyl and other issues. Congress also raised, when necessary, human rights or democratic deficits. Congressional attention was especially manifested immediately before, during and after the Orange Revolution, with Congress strongly supporting the democratic aspirations of the Ukrainian people.

Thus, it readily called out human rights abuses and democratic deficits, especially in the late Kuchma period and during the Yanukovych years. For instance, Congress was very active in defending the politically-motivated imprisonment of Yulia Tymoshenko and others. Regarding resolutions, hearings or Congressional statements that sometimes criticize constructively the actions of the Ukrainian authorities’ it is important to underscore that often in Washington – both within and outside of Congress – Ukraine’s biggest critics are often Ukraine’s strongest supporters – people who genuinely care about the country and want it to succeed as a secure, thriving European democracy.

There were also important pieces of legislation like the Nunn-Lugar Act, which provided $1.3 billion to help safeguard and dismantle weapons of mass destruction, and numerous broader appropriations bills which provided nearly $5 billion in bilateral assistance alone to Ukraine between 1991-2013. This assistance included military/security as well as projects focusing on economic growth, energy security, health, agriculture and democracy, human rights and good governance.

Clearly much of this was designed to assist Ukraine in becoming a more secure, democratic, prosperous, safer, and healthier country. Keep in mind that Congress has the power of the purse -- the U.S. Constitution grants Congress exclusively the power to appropriate funds. Sometimes Congress has appropriated additional funding for Ukraine beyond the Administration’s formal request or supported the work of specific organizations such as the U.S.-Ukraine Foundation. Indeed, for several years in the mid-1990’s, Ukraine was the third largest recipient of bilateral U.S. assistance in the world. This funding encompassed not only military and security aid, but also assistance in the economic, energy, humanitarian, health, democracy and good governance realms.

Post-Maidan: 2014-2020

Not surprisingly, Congress began to pay even more attention to Ukraine during the Euromaidan Maidan Revolution of Dignity, with several high-profile visits by Senators to the Maidan, and with the passage of resolutions both in the House and Senate in early 2014. These resolutions supported the Ukrainian people’s aspirations for freedom and democracy and called for consideration of sanctions against those responsible for the use of force against peaceful demonstrators.

Congress’ focus on Ukraine expanded further following Russia’s flagrant violation of international norms with the illegal occupation of Crimea and aggression in the Donbas. Congressional efforts have centered on three main pillars – military/security assistance, both lethal and non-lethal; sanctions against Russia and their Ukrainian colluders; and economic and technical assistance for Ukraine. This activity was especially intensive in 2014-2015.

How has Congressional activity manifested itself since Russia’s invasion? Never have we seen more statements, press releases, letters to Administration officials, hearings, briefings, and meetings with visiting Ukrainian officials than since the beginning of 2014. Never have so many Members of Congress, especially Senators, visited Ukraine, especially in 2014 and 2015 --during the most acute phase of the war. Never have there been so many public hearings on Ukraine, especially in the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which plays an especially key role in US policy towards Ukraine.

Never have there been as many media appearances by Senators and Representatives about Ukraine, in this case regarding Russian aggression. Never has there been as much interaction between Members of Congress (by which I mean both the Senate and House of Representatives) and the Executive Branch on Ukraine and Congressional pressure on the Administration for a more assertive US policy to counter Russia’s aggression.

And let us recall President Poroshenko’s address to a joint-session of Congress in September 2014, a relatively rare occurrence by a foreign leader and one which was extremely favorably received by Congress. Also noteworthy is that this was the second appearance by a Ukrainian president before Congress within a decade, the earlier one being President Victor Yushchenko’s in April 2005. In this, Ukraine joins a very small, select group of America’s friends and allies who have had more than one leader speak, much less within a decade.

With the war, a greater number of Congressional institutions began paying more serious attention to Ukraine. Before 2014, it had been the Helsinki Commission and the Congressional Ukrainian Caucus that had historically displayed the greatest level of activity with respect to Ukraine, albeit in different ways, reflecting their different structures and mandates. The House and Senate Appropriations Committee subcommittees that were responsible for financial assistance to Ukraine also played an essential role.

With the Russian occupation of Crimea, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in particular and House Foreign Affairs Committee stepped up their level of activity on Ukraine to an unprecedented degree, both reflecting and encouraging Ukraine’s ascent as one of the top U.S. foreign policy priorities. Because of Russia’s military aggression, other committees such as the Senate and House Armed Services committees also greatly increased their engagement on Ukraine.

At the same time, the Helsinki Commission and the House Ukrainian Caucus remained active. In February 2015, a Senate Ukraine Caucus chaired by Senators Rob Portman (R-OH) and Dick Durbin (D-IL) was inaugurated. This caucus has remained actively engaged with respect to Ukraine, especially on military/security issues. An important point to keep in mind is that members of the Helsinki Commission and the House and Senate Ukraine Caucuses are often also key members of other committees that focus on Ukraine, which has often helped enhance their work in those committees.

Congressional involvement has also manifested itself in the international arena, for instance, at the NATO Parliamentary Assembly or the 56-country OSCE Parliamentary Assembly (OSCEPA). To cite one example, at the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly meeting held in Baku in 2014, a resolution was introduced by Helsinki Commission Chairman Sen. Ben Cardin (D-MD) on Russia’s violation of international commitments by annexing Crimea and directly supporting armed conflict in Ukraine. It was adopted by a 3-1 margin, despite fierce Russian opposition. The U.S. has strongly supported subsequent resolutions by Canada and Ukraine following up on and expanding the original 2014 resolution. It should also be noted that members of Congress and especially Helsinki Commission staff have observed virtually every national election in Ukraine since 1990, most often as member of the OSCE PA missions.

The most concrete manifestation of Congressional activity on Ukraine has been legislation; most notably, the two Public Laws signed by the President in 2014 – both received strong bipartisan support, something that has not been the norm in recent years given the highly charged partisan environment.

On April 3, 2014, soon after Russia’s invasion, President Obama signed into law the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Ukraine Act of 2014. This legislation authorized aid to help Ukraine carry out reforms; authorized security assistance to Ukraine and other Central and Eastern European countries; and required the President to impose visa bans and asset seizures against persons in Ukraine and Russia responsible for violence or undermining Ukraine’s territorial integrity. He also signed into law a bill requiring Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty and Voice of America to increase broadcasting in eastern Ukraine and Crimea.

Nine months later, on December 18, 2014, President Obama signed the Ukraine Freedom Support Act, permitting the President to impose sanctions on Russian defense, energy and other firms and foreign persons. The Act also authorized increased military, economic, energy and democracy assistance for Ukraine as well as increased funding for U.S. Russian-language broadcasting to the region.

It is an exceedingly rare occurrence in the U.S. Congress to have two major pieces of legislation devoted to just one country within nine months. One point of context for those not familiar with the workings of Congress: the vast majority of legislation that is introduced never becomes law. That which does often takes months and years to wind its way through the legislative process. Legislation first must pass both chambers of Congress, the House and the Senate, in order to be signed into law by the President.

The passage of these two bills – both of which were initiated in the Senate -- was an impressive and relatively rare display of bipartisanship in both the House and Senate. It was a strong manifestation of the support of the American people, through their elected representatives, for Ukraine. Furthermore, there been numerous resolutions (which express the sense of the Congress on an issue) supporting Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

There are also examples of bills on Ukraine that have passed one chamber of Congress but not the other. This is not because one chamber is necessarily more pro-Ukrainian than the other, but rather it is the function of the complexities of the legislative process. Passing legislation in any democracy is not a straightforward process and becomes even more challenging when there is a bicameral legislature, as there is in the U.S. Congress. One example of this was the Stand for Ukraine Act of 2016, which passed the House and not the Senate.

Having legislation enacted into law by it passing both Congressional chambers and being signed by the President – i.e. becoming an Act, is very significant, but it is not always enough. The Executive Branch has to execute the laws. There have been times and reasons why Administrations have not fully or enthusiastically enforced laws, including on occasion those enacted in support of Ukraine. Nevertheless -- and critically, in Ukraine’s case -- Members of Congress have continued to press Administrations for actions, to execute the laws fully.

While the vast majority of legislation introduced doesn’t become law, the mere introduction of a bill or resolution often is of value. Indeed, every kind of Congressional activity matters – hearings, briefings, statements in the Congressional Record, press releases and press conferences, Congressional appearances in the media or at public events, meetings, letters to the White House/Administration. They have numbered in the many, many hundreds since 2014.

All are vehicles in conveying Congressional interest and concern to involved parties. They are also essential in underscoring Congress’ interest in Ukraine with the Executive Branch. Indeed, the interaction between Congress and the Executive branch on Ukraine has helped to inform and encourage the Administration to take more robust policies in support of Ukraine. While this has been a pattern over the course of the last century, it has been especially evident in the last six years – whether it be Congress pressing President Obama on lethal weapons or President Trump on sanctions.

Language from bills or resolutions that are introduced often finds its way into larger legislation, including as part of larger bills that authorize or appropriate assistance. One example is the inclusion of specific language on Ukraine in the massive National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). For 2019, it authorized the allocation to the Defense Department of $250 million dollars for security assistance to Ukraine, including $50 million for lethal weapons. This NDAA also includes major clauses from the Ukraine Cybersecurity Cooperation Act, which passed the House earlier.

There has often been language on Ukraine in much more massive, comprehensive bills that fund the entire US government budget. U.S. bilateral assistance to Ukraine alone of all kinds, including military/security, economic, democracy building, health, environment, has totaled an estimated $8 billion since 1991.

Perhaps the most significant non-funding bill on Ukraine in the last several years has been CAATSA (Countering American Adversaries’ Through Sanctions Act). This legislation was overwhelmingly adopted on a bipartisan basis and signed, albeit reluctantly, by President Trump in August 2017. Much of CAATSA is targeted at sanctioning Russia for its election interference and other attempts to undermine American democracy. But it also includes a very strong Ukraine component with many references to Ukraine.

It codifies six executive orders signed by Obama in response to Russia’s aggressive actions in Ukraine, many of which had been called for but not mandated in Congress in various previous legislation. These provisions targeted Russia’s financial services, energy, defense and other sectors, thereby preventing any President from revoking them without Congressional consent. Among other things, CAATSA also authorizes energy security and other assistance to Ukraine and asserts a policy of non-recognition of Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Much of the language in CAATSA on Ukraine had been in other proposed legislation authored by Sens. Ben Cardin and John McCain [R-AZ] but was folded into this more comprehensive legislation.

Pieces of legislation acted upon in 2018 included resolutions in the House and Senate condemning Russia’s attack on Ukrainian naval vessels, a Senate resolution marking the 5th anniversary of the Revolution of Dignity, and a House resolution calling for the cancellation of Nord Stream 2. In 2019, legislation acted upon on Ukraine included House passage by an overwhelming vote of 427-1 of the Crimea Annexation Non-recognition Act.

Many other bills and resolutions on Ukraine or on further sanctions on Russia due at least in part to its violations of Ukraine’s territorial integrity have been introduced and are making their way through the legislative process.

Ukraine was at the center of Congressional attention in late 2019 and early 2020 because of the impeachment proceedings against President Trump for his conduct in Ukraine. While during the House impeachment proceedings and the Senate trial there were frequent references to corruption in Ukraine, there was also considerable acknowledgement that Ukraine under its current leadership was taking steps to combat it. What was also very evident in both the testimony and remarks during was the fulsome, vocal, strong, bipartisan support for Ukraine’s struggle against Russian aggression.

Despite criticism of Ukraine from several Republicans for its alleged interference in the 2016 elections, nobody challenged the notion that the United States should continue to stand with Ukraine in its fight against Russia. Supporting Ukraine in opposing Russian aggression is taken as a given in the United States Congress

This bipartisan support was evident in the overwhelming passage of key legislation affecting Ukraine in the waning weeks of 2019.

On December 19, 2019, President Trump signed bicameral appropriations legislation approving nearly $700 million for security and foreign assistance for Ukraine in FY2020, a slight increase over FY2019. The aid includes military/security assistance to help Ukraine fight Russia’s aggression. It also encompasses vital non-security assistance that supports Ukraine’s democratic trajectory, rule of law, anti-corruption, economic development, energy, health and agriculture.

In addition to the myriad of diverse Executive branch Ukraine programs funded by Congress, there is one specifically in the Legislative branch -- the Open World international exchange program. More than 3,400 Ukrainians have participated in this program in the last 15 years, including hundreds of members of the Verkhovna Rada.

The end of 2019 also saw passage of the massive National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for 2020, which imposes sanctions related to Russia's Nord Stream 2 pipeline and bars military-to-military cooperation with Russia. The NDAA also includes the reauthorization of $300 million of funding for the Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative.

Several pieces of legislation on Ukraine have been introduced during the impeachment process. House and Senate members of the U.S. Helsinki Commission introduced the Ukraine Religious Freedom Support Act opposing violations of religious freedoms by Russia and its proxies in the occupied territories.

A bipartisan resolution was introduced in early 2020 by the Co-Chairs of the House Ukraine Caucus “reaffirming U.S. support for the Ukrainian people and Ukraine’s democratic trajectory, free from Russian malign influence.” Senators and Representatives from both parties continued to express support for Ukraine, including during a February 2020 visit to Ukraine by key members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee – Republicans Ron Johnson and John Barrasso and Democrat Chris Murphy.

Informing Congress and Outside Advocacy

An important, though far from sole, factor encouraging Congressional interest in Ukraine, has been advocacy by the Ukrainian-American community and other numerous friends of Ukraine, particularly in Washington.

Congress is the branch of government closest to the people. In contrast with the pre-independence era, when the Ukrainian-American community was almost exclusively the outside driver of Congressional support, since independence, there are many NGOs with involvement in Ukraine that encourage Congressional support for Ukraine’s security, democracy and the rule of law. Indeed, a whole network of authoritative, pro-Ukrainian American NGOs, think-tanks and former government officials exists that is respected and listened to by Members of Congress and their staffs.

Among the most consistently active of these over the years have been Washington-based NGOs such as the International Republican Institute (IRI), the National Democratic Institute (NDI), and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Many prominent Washington think-tanks have also been involved with Ukraine over the decades – at times more intensively, at times less so. The Atlantic Council has been especially dynamic since 2014.

Nevertheless, the role of the Ukrainian-American community remains crucial. Advocacy work on behalf of Ukraine in Congress has also expanded since 2013. This advocacy has ebbed and flowed. It previously peaked in the decade leading up to the fall of the Soviet Union – with its focus on human rights, political prisoners and calls for independence. It continued for a few years following independence, with a focus on concrete assistance to the new Ukrainian state.

The heavy lifting of Ukrainian-American advocacy during this time had been done by the highly politicized post-World Was II (3rd wave) emigration and their children. Since 2014, however, the new and previously largely politically inactive post-independence (4th wave) emigration has come out of the woodwork and become considerably more engaged in advocacy.

In recent years, there have been many more advocacy events, notably those organized by the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America’s Washington office, the Ukrainian National Information Service (UNIS). These “Ukrainian Days” have been held several times per year, where American citizens meet with Congressional offices in Washington. There have also been many efforts on both the national, and state and local levels, by Ukrainian-American organizations and individual activists to reach out to Senators and Congressmen who represent them through social media, the more traditional email and phone calls, and direct person-to-person contacts.

Following Russia’s invasion, the U.S.-Ukraine Foundation initiated a Friends of Ukraine Network (FOUN) which includes a number of former U.S. ambassadors to Ukraine as well as to other countries and international organizations and other former officials from the State Department, U.S. Agency for International Development, Defense Department and Congress. It also includes experts from think-tanks and representatives of key NGOs involved with Ukraine. FOUN came up with recommendations for sanctions shortly after the invasion of the Donbas and advocated for their implementation with Congress and the White House.

In 2017, separate FOUN task forces came up with policy recommendations for U.S. assistance to Ukraine in four areas: national security, economy and energy, humanitarian issues, and democracy and civil society. These task forces – especially the national security task force – interacted with key Congressional offices to help ensure concrete support for Ukraine. In March 2018, the FOUN issued “An appeal for decisive action in Ukraine’s fight against corruption” to the Ukrainian government and Verkhovna Rada. In 2019, the FOUN issued an updated set of policy recommendations for U.S. Assistance for Ukraine in the following areas: National Security, Economic Security, and Democracy and Civil Society.

Another feature of outside activity has been the engagement of organizations and individuals also concerned with the implications of Russia’s flagrant violations on Ukraine’s territorial integrity elsewhere, such as American organizations representing Central and Eastern European groups, notably the Baltic community. American Jewish organizations have also actively encouraged stronger U.S-Ukraine relations.

In addition to US citizen advocacy, Ukrainian officials and Verkhovna Rada members often also interact with Senators and House members – primarily in Washington, Kyiv, or at multilateral fora. Ukraine’s Embassy to the United States has also interacted often with Members of Congress throughout the years of independence – not only on the level of Ambassador, but other Embassy diplomats who frequently would meet and exchange information with Congressional staff. Indeed, given how busy Members of Congress are, meetings, exchanges of information, and advocacy efforts, in general, have often been directed at Congressional staff.

As anyone who has familiarity with how Washington works knows, staff play a crucial role -- especially staff of key committees – in preparing resolutions, hearings, statements, press releases and memos. Many of these professional staffers have also had a history of interest in and support for Ukraine.

Conclusion

Why so much Congressional interest in Ukraine over the last century? Yes, there were constituent politics where Congressmen and Senators responded to Ukrainian-American voters – something that U.S. legislators tend to take seriously. But there have also been many Senators and House Members who had hardly any Ukrainian-American voters, yet, for various reasons, believed in the idea of an independent, free, democratic Ukraine in which human rights were respected, especially in light of Ukraine’s tragic 20th century history. There are more even now who are outraged by Russia’s occupation of Crimea and the ongoing manufactured war in the Donbas that so grossly has flouted the rules-based international order.

The hyper-partisan U.S. Congress has not agreed on much in recent years, but there has been a broad consensus when it comes to Ukraine, even during and following the politically highly-charged impeachment proceedings stemming from President Trump’s conduct with Ukraine. With few exceptions, both Republicans and Democrats in both the Senate and House have been supporters of an independent, democratic Ukraine. And this follows the trend of broad bipartisanship on Ukraine that has existed over the course of the last century.

This bipartisanship is nothing new. While one can argue that during the Soviet era, Republicans tended to be more anti-communist/anti-Soviet, there was always a strong current within the Democratic party that understood the Soviet threat and supported Ukraine as well. And, of course, both parties these days well-recognize the threat to Ukraine and to the international order posed by Putin’s Russia.

The over-arching theme of Congressional activity can be boiled down to one word: FREEDOM. National rights, human rights, human dignity, democracy, sovereignty, territorial integrity – all of these issues which Congress has addressed in one form or another over the course of the last century are intimately linked. What lies at their core is the notion of freedom.

Whether it be Captive Nations with its emphasis on freedom for nations; freedom for religious institutions such as the Ukrainian Catholic and Autocephalous Orthodox Churches; calling for individual freedoms, including the myriad of activity on behalf of Ukrainian political prisoners; legislation and resolutions on the genocidal Holodomor -- focusing as they did on this most cruel deprivation of freedom – death by starvation.

This also applies to NATO legislation – designed to enhance Ukraine’s security freedom; or Permanent Normalized Trade Relations (PNTR) – aimed at strengthening economic freedoms; or the numerous hearings, briefings, statements on the state of democracy, human rights and rule of law – all these efforts are all about expanding the scope of freedom, about enhancing the rights and freedoms of the Ukrainian people. Whether it be the Captive Nations resolution and commemorations of Ukraine’s 1918 independence in Congress prior to independence in 1991, or, most significantly, the multitude of Congressional legislation and other efforts in recent years to help Ukraine counter Russia’s aggression and preserve its sovereignty and territorial integrity. In all of these Congressional actions, freedom lies at the core. An independent, sovereign, democratic Ukraine, after all, is a free Ukraine.

The U.S. Congress over the course of the last century has been in the forefront of defending and promoting both freedom for Ukraine and freedom in Ukraine. Congress can take great pride in its strong, bipartisan support of Ukraine. But there is still much work ahead to assist Ukraine in continuing to fend off Russian aggression and to support the prosperous, democratic European future that Ukrainians have freely chosen.

--

Orest Deychakiwsky worked at the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (the U.S. Helsinki Commission), a U.S. government agency composed mostly of U.S. Senators and House members, from 1981-2017. His many responsibilities throughout his more than 35 years of service included Ukraine. He served as a member of numerous official U.S. delegations to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe and its predecessor, the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), and was an OSCE election observer in more than 30 elections in Ukraine and eight other countries. He currently serves as Vice-Chair of the Board of Directors of the U.S.-Ukraine Foundation and Co-chairman of the Friends of Ukraine Network (FOUN) Democracy and Civil Society Task Force, Senior Advisor of the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council and writes a periodic column for The Ukrainian Weekly called “Washington in Focus.”