Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

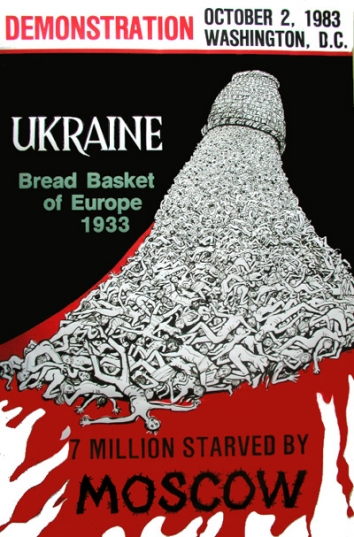

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

UKRAINE’S DIASPORA

More than three million Ukrainians have fled their country. See who they are.

More than three million Ukrainians have fled their country. See who they are.

By David Leonhardt and Ian Prasad Philbrick

The New York Times, New York, NY, Fri, Mar 25, 2022

Refugees from Ukraine arriving in Medyka, Poland. Mauricio Lima for The New York Times

During the early days of the war in Ukraine — as Russia was attacking the city of Mykolaiv, near the Black Sea — Anna Sevidova decided to hide in her basement with her son. She figured it was their best hope for staying safe.

But when a missile exploded in their yard, a fragment of it shot into the basement and struck Anna in the face. With a piece of the missile lodged in her nose, she crawled through her collapsed home, dragging her son underneath her to protect him. Both of them were covered in blood. “I thought those were the last seconds of my life,” Anna said.

Instead, they survived and soon fled to Moldova, which borders Ukraine. They are among the roughly 10 million Ukrainians, or about one-fourth of the country’s population, who have left their homes in the past month. Of the 10 million, about seven million have moved to other parts of Ukraine, while more than 3.5 million have left the country.

It is the largest displacement of Europeans since World War II, according to the United Nations. More than half of Ukraine’s children are no longer living in their homes.

The numbers are so large because Russia is using a deliberate strategy of attacking civilians to destabilize Ukraine. This flood of refugees has created major challenges in Europe. Moldova, for example, has taken in more than 100,000 Ukrainians, despite being one of Europe’s smallest and poorest countries. About 90 percent of those refugees are living in private homes. “For now, society is showing a great degree of empathy,” Nicu Popescu, Moldova’s foreign minister, told The Times.

President Biden announced yesterday that the U.S. would accept 100,000 refugees and donate $1 billion to help European countries deal with the surge in refugees. Previously, the Biden administration’s has set a cap for refugees, coming from anywhere in the world, of 125,000 per year.

Today’s newsletter summarizes some of the best journalism about Ukraine’s refugees, including photographs that Sarah Hughes, a Times photo editor, selected.

A family from Odessa, Ukraine, at a temporary shelter in Chisinau, Moldova. Mauricio Lima for The New York Times

- “One day you are driving to the dentist. The next you are whispering with strangers in a dark basement,” our colleague Sabrina Tavernise writes, as part of a collection of short profiles of fleeing mothers and children. “It is a moment when instinct — to save your children, to get through the next checkpoint — takes over and emotions are blocked. Finally, it is the shocking realization that suddenly, unwillingly, you are a refugee, dependent on the generosity of strangers, no longer a middle-class person in charge of your own life.”

- Natalia Lutsenko — who has fled to Poland from the bombed-out northern town of Chernihiv — told The Associated Press that she still could not comprehend what Vladimir Putin was thinking: “Why is he bombing peaceful homes? Why there are so many victims, blood, and killed children, body parts everywhere?”

Waiting at the train station in Lviv, Ukraine, this month. Ivor Prickett for The New York Times

- Lviv — the largest city in western Ukraine, about 45 miles from Poland — has become a safe haven for many Ukrainians, as Stefanie Glinski describes in Foreign Policy. But they also wonder whether Russia will soon begin attacking it regularly. And daily life is often a crowded struggle. “We had a comfortable life and a nice apartment,” Ludmilla Marchuk, a 44-year-old mother of two said tearfully. “I just want to go home.”

Pushing onto a train heading west out of the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv. Lynsey Addario for The New York Times

- Poland has accepted the most refugees by far — about 2.2 million, according to the U.N. (Next on the list are Romania and Hungary, each between 300,000 and 600,000.) The Washington Post has published drawings by children at the train station in Przemysl, a Polish city near the Ukrainian border. And the Times has reported that Przemysl, an elegant little city, has transformed itself nearly overnight to feed, house and help refugees.

Ilona Koval, center, choreographer for the Ukrainian national figure skating team.

Laetitia Vancon for The New York Times

- Moldova has taken in about one refugee for every 25 of its citizens. This Times video looks at the situation there — and allows you to hear Anna Sevidova tell her own story.

- “The best that humanity has to offer”: A Kyiv Independent journalist spent a day with volunteers who deliver food, rescue pets and evacuate people from nearby war zones.

A gymnasium in Novoyavorivsk, Ukraine, was converted into a shelter for displaced people.

Brendan Hoffman for The New York Times

- For anybody who wants to make a donation to help Ukrainian refugees, there are many worthy options (but watch out for scams). One option recommended by this Times Opinion guide is Mercy Corps, which is supporting local organizations in Poland, Romania and Ukraine. Another option is World Central Kitchen, founded by the chef José Andrés.

NOTE: David Leonhardt is a senior writer for The New York Times. He writes The Morning, The Times’s flagship daily newsletter, and also writes for Sunday Review. He has worked at The Times since 1999 and has previously been an Op-Ed columnist, Washington bureau chief, co-host of “The Argument” podcast, founding editor of The Upshot section and a staff writer for The Times Magazine. He also led a strategy group that helped Times leadership shape the newsroom’s digital future. In 2011, he received the Pulitzer Prize for commentary. He is a third-generation native of New York City.

Ian Prasad Philbrick is a writer for The Morning newsletter.

LINK: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/25/briefing/ukraine-refugees-biden.html