Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

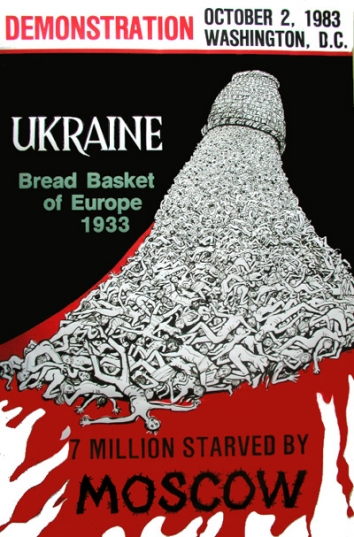

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

UKRAINIAN AMERICANS STRUGGLE TO GET FLEEING RELATIVES INTO UNITED STATES -- Part 3

By Mark Fisher, Maria Sacchetti and Mark Shavin

By Mark Fisher, Maria Sacchetti and Mark Shavin

Washington Post, Wash, D.C., Sat, Mar 19, 2022

They are staying in the home of the pastor of Life of Victory Church in Renton, Wash., a fellow Ukrainian who came to the United States 20 years ago. How long they’ll be there, they do not know. Their neighbors in Ukraine tell them that “our city is destroyed,” Roza said.

“We left everything. Our albums with pictures. Everything. It makes us so sad. We don’t know if we’ll ever have the opportunity to come back,” Roza said. For now, they have only thanks, for their safety and for being together. Roman plans to sing songs of gratitude at a concert in Seattle on April 3.

Even a visa does not guarantee such a happy ending for some Ukrainian families. Oksana Palchevska, a postdoctoral fellow in microbiology who came to Birmingham in 2020 to join a University of Alabama research project on the coronavirus, has been working here while her husband and 12-year-old daughter Sofiia remained in Ukraine.

“I was stupid not to take my family with me, I see now,” Palchevska said. But at the time, few people foresaw this kind of conflagration. Last December, her husband Sergii and Sofiia got J-2 visas, granted to immediate relatives of a nonimmigrant who is working in the United States.

But earlier this year, Sergii, a scientist who had been working at an institute in Poland, made one last trip back home to Kyiv to say goodbye to his family before heading to the United States. He stayed too long, Palchevska said, and now is stuck in Ukraine because the country is requiring men to stay to fight the Russians.

Sofiia had remained in Warsaw with Palchevska’s sister and parents. Luckily, the sister holds a U.S. tourist visa, so Palchevska hopes her sister will be allowed to bring Sofiia to Alabama this weekend. Palchevska, 36, has sent letters asking U.S. officials to let her daughter into the country without a parent accompanying her, but she won’t know whether it will all work out until the day of the flight.

Palchevska is allowing herself a bit of optimism that Ukraine will hold off the Russians, Sofiia will be with her soon and they will edge into an American life. Palchevska got a driver’s license and is looking to get her first car so she can take her daughter to her American school.

“I feel a little guilty that I should be in my country to help,” Palchevska said. “I don’t fit into this country yet. Mostly, I work. But there are so many more opportunities here.”

Protesters carry a Ukrainian flag in the District of Columbia last month.

(Leigh Vogel for The Washington Post)

Fisher and Sacchetti reported from Washington and Shavin reported from Atlanta. Nick Miroff in Washington contributed to this report.

NOTE: Marc Fisher, a senior editor, writes about most anything. He has been The Washington Post’s enterprise editor, local columnist and Berlin bureau chief, and he has covered politics, education, pop culture and much else in three decades on the Metro, Style, National and Foreign desks.

Maria Sacchetti covers immigration for the Washington Post, including U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the court system. She previously reported for the Boston Globe, where her work led to the release of several immigrants from jail. She lived for several years in Latin America and is fluent in Spanish.

LINK: Ukrainian Americans struggle to get fleeing relatives into United States