Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

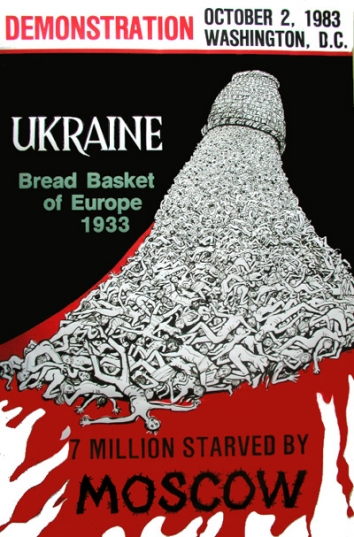

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

U.S. FIRM WINS UKRAINIAN OFFSHORE GAS RIGHTS

Kyiv Post, Kyiv, Ukraine

Kyiv Post, Kyiv, Ukraine

Fri, August 2, 2019

Trident Acquisitions is planning to make the largest single international investment of $1 billion in Ukraine since the country’s 2014 EuroMaidan Revolution

Ilya Ponomarev, CEO of the publicly traded U.S. company Trident Acquisitions and its Ukrainian subsidiary, Trident Black Sea, asks a question to Chargé d'Affaires of the U.S. Embassy in Ukraine William Taylor at a meeting of the U.S.-Ukraine Business Council in Kyiv on June 26, 2019.

It could end up as the largest single foreign investment in Ukraine since the country’s 2014 EuroMaidan Revolution, as well as a welcome boost to Ukrainian and European energy security.

It may also be a symbolic ribbon-cutting moment and a litmus test for foreign companies that could be cautiously waiting at the door of the country’s lucrative but largely untapped natural gas sector.

That is, if hesitant outgoing Ukrainian ministers — and the ones that will soon replace them — sign off and allow it to happen.

On July 26, Ilya Ponomarev said that his publicly-traded U.S. company Trident — of which he is a major shareholder and CEO — had emerged the winner in a contentious tender to explore, extract and produce natural gas from part of Ukraine’s Black Sea shelf.

Pending government approval of the decision, the company will have a 50-year mandate for a gas-rich zone close to the Romanian coastline known as Dolphin. But that approval seems increasingly unlikely. Critics in the current government argue that the tender was not given enough time to be truly competitive.

They would prefer to repeat the competition, even though the six-member interdepartmental commission on Production Sharing Agreements (PSAs) of the Ministry of Coal and Energy decided that Trident had the most attractive proposal.

American investment

Ponomarev, his Western business partners and American hedge fund investors have hungrily eyed the opportunity off Ukraine’s southwestern coastline for years.

Trident raised at least $200 million for the venture, 90 percent of that from U.S. investors, in its initial public offering on the New York-based NASDAQ exchange last year. It has since partnered with European companies and signed exclusive agreements with them that moved to hinder the competition, giving them a substantial edge in pitching for Dolphin.

The Trident group consists of Trident Acquisitions, a U.S. company based in New York — but incorporated in the State of Delaware, widely seen as an American tax haven — and Trident Black Sea, its Ukraine-based subsidiary. Ponomarev co-founded the firms.

In a July 30 interview with the Kyiv Post, Ponomarev said that $200 million is ready to be invested immediately. Partner companies from Romania — GSP Offshore — and Ireland — San Leon Energy — are contracted and standing by to play their technical roles in the joint venture.

Trident could ultimately invest as much as $1 billion into natural gas extraction and production at the Dolphin site, raised from shareholders and investors if their discoveries warrant it, Ponomarev said.

It is a lucrative opportunity. State geological estimates of the 9,500 square kilometer offshore site put natural gas reserves at some 286 billion cubic meters, although not all of it can be recovered.

Before the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ukrainian company Chernomorneftegaz, or CNG, was extracting about 2 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year from offshore reserves. Ukraine is suing Russia in the Hague for $5.2 billion in losses stemming from the Russian seizure of CNG.

The country could use the investment. Ukraine wants to pivot away from Russian energy dependence and has its own vast reserves of untapped natural gas — about a trillion cubic meters in total, according to multiple expert assessments.

About 96 percent of Ukraine’s hydrocarbon reserves, however, are still undeveloped, and production is stuck at around 21 billion cubic meters of gas annually — three times less than peak production during Soviet years.

But Ponomarev, a long-time energy executive and Russian opposition figure who voted in 2014 against his native country’s illegal annexation of Ukrainian Crimea, when he was a member of Russian parliament, isn’t quite ready to celebrate. The fight is not over, he said.

He says that Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman will not sign off on the project, and will instead use his last month in office to oppose it and call for another, longer competition.

One of his rumored successors, National Security and Defense Council Secretary Oleksandr Danylyuk, might not be helpful either.

Short-lived victory?

Groysman and Danylyuk’s opposition can be seen either as cautious situation management of a sensitive issue and safeguarding an important resource, or it can be seen as a politically motivated intervention in what was a fair and competitive process.

“Yes, we won,” says Ponomarev, who took a break from holding court at the Hyatt hotel on July 31 to speak with the Kyiv Post. “But we will celebrate when Mr. Groysman actually signs off.”

Ponomarev has positioned himself firmly as a Ukrainian patriot and energy independence advocate since he moved to Kyiv in 2014. He has been given Ukrainian citizenship, and is renouncing his Russian status.

The Dolphin venture is a passion project for him and it has a lot of supporters, including the tentative backing of the Association of Gas Producers of Ukraine (AGPU).

The Ukrainian prime minister, however, is not so supportive, and has stated he will not recognize or support the July 26 decision in favor of Trident.

On July 27, Groysman said the tender was not competitive enough and did not attract the attention of big enough companies, citing the international energy giants Exxon and Shell as examples. He said he would push for another competition.

Ponomarev says the government cannot repeat the competition just because the companies they wanted did not apply.

On July 29, Danylyuk added to Trident’s headache by echoing and supporting Groysman.

“The decision on the new competition for the shelf is definitely correct… The main problem of the (previous) competition was the artificially constrained time limits for analyzing the deposits and preparing bids. Serious companies won’t take part in such a competition,” Danylyuk said of the tender, in which interested companies had 60 days to submit a proposal.

Ponomarev says that he understands the disappointment of those who had hoped multinational energy giants would leap on Dolphin, but it does not justify political intervention in what was a fair process.

Companies interested in the opportunity had more than enough time to get into gear, register their interest and submit their proposal, he says. Trident, for example, was established in March 2016 for the explicit purpose of targeting the Ukrainian Black Sea — a long-known area of opportunity.

Not everyone agrees with Ponomarev. Energy and law experts who spoke with the Kyiv Post are divided on the competition and its outcome.

While most broadly agree that Ponomarev and Trident are a welcome addition to the Ukrainian natural gas sector, there is also a feeling that the competition for Dolphin was not credible and should be repeated.

Roman Opimakh, Executive Director of the Association of Gas Producers of Ukraine, who has been tentatively supportive of Trident Acquisitions before, said: “The Commission gave its recommendation on the winner, but the final decision has to be taken by the government.”

“The tender is supposed to be relaunched, and in this time… it will be organized by the government in a proper way, with respect to best international practices: a longer period for the bid preparation — six months, not two — easy access to state geological data and wider promotion of the production sharing agreement tender by top officials.”

Repeating the competition in such a way will bring a “credible and strategic international player” that can develop the offshore assets of Ukraine, Opimakh added.

But the reason why international companies did not bid on the Dolphin opportunity wasn’t an insufficient window of time, according to Ponomarev. It was a lack of motivation, capital, or capacity.

Companies such as Shell, ExxonMobil, Total, BP or Chevron will not invest in Ukraine while they are also heavily invested in Russia. At the same time, with a $55 million buy-in, the Dolphin site is far too small a project for them, he adds.

Furthermore, at one time or another, energy giants such as Shell, ExxonMobil and BP as well as others had shown considerable interest in Ukraine, with some going as far as signing agreements with the government. For one reason or another, they all left the Ukrainian market.

Trident, on the other hand, is ready to make a substantial investment, having founded their company in order to do so — but the firm is also disheartened that their commitment and win can be so easily discarded, Ponomarev says.

“Firstly, they are sending a signal to investors that the rules you make can be changed after the fact,” he says. “Secondly, they don’t take into consideration that all of our commitments so far have borne expense. Money was invested for a period of time. All of this costs something.”

“There is not a big line of investors… to come into Ukraine, who are willing to wait indefinitely,” Ponomarev adds.

There is one company that is especially disappointed in Trident’s tender win: UkrGasVydobuvannya, commonly called UGV, a state gas producer that is a fully owned subsidiary of state-owned Naftogaz.

Oleksandr Romaniuk, First Deputy Chairman of the Board, told the Kyiv Post that the state-owned company has the first rights to a section of the gas-rich offshore field and was still arguing this claim in the courts.

“It is good to have an open tender but we did not bid because the whole process was illegal… I am sure they (Ponomarev and Trident) could do a great job — the problem is with the process,” Romaniuk said of the two-month competition. Still, he added that UGV could be open to a joint venture with Trident if its main shareholder, Naftogaz, was interested.

Trident’s pitch

Trident made an attractive proposal to win the rights to offshore extraction and production at the Dolphin site.

While the Ukrainian government wanted a minimum investment of $55 million, Trident brought a minimum of $200 million from U.S. hedge fund investors — and up to $800 million more if needed.

While the Ukrainian government usually demands royalties of between 3 percent and 11 percent for gas producers, Trident offered extremely attractive terms, according to Ponomarev: 30 percent at the start, and 70 percent if the wells meet their full capacity.

“I am not an altruist,” Ponomarev says. “But we want Ukraine to prosper and to grow. And we want to open the gate for others to come. That’s why, for me, it is an extremely important project which would help transform the Ukrainian economy, and the oil and gas sector in particular.”

Trident also has $14 million earmarked for so-called “social obligations” in the coastal region and plans to partner with and invest in Odesa universities, while establishing a tech and science startup hub there, according to Ponomarev. The firm has also partnered with a leading “clear water” company for its environmental initiatives, mindful of keeping the Ukrainian coastline clean and safe, he claims.

As a publicly-traded U.S. company, Trident falls under the jurisdiction of the US Securities and Exchange Commission and other federal agencies. Although it is registered in the known tax haven of Delaware, Trident has been complying with all relevant filings and requirements, Ponomarev says.

“We are an American, publicly-traded company — we cannot do shady deals,” he says. “We cannot pay bribes, we cannot avoid taxes, we need to do everything in a very open and transparent manner. We are bringing a totally different business practice to the table.”

It is, however, a Euro-American venture, Ponomarev says. The gas would be for Ukrainian consumers but could also be exported into Romania and even deeper into Western Europe.

A key tender requirement for the Ukrainian government was to show that the bidders already had offshore projects, which is why the Dublin-based exploration company San Leon Energy was an important partner.

Essentially a British company registered on the London Stock Exchange, San Leon is already extracting some 50,000 barrels of oil per day offshore from the Niger Delta.

Another key operating partner in Trident’s bid is the Romanian company GSP Offshore, exclusively contracted to Trident — according to Ponomarev — and arguably the Black Sea’s top player for extraction and production of natural gas. GSP currently operates seven offshore drilling rigs and is already developing Romanian gas fields less than 50 kilometers from Dolphin.

Trident accepts that there are some risks to the venture and its assets, not least of which is the Russian coast guard and navy, which have become increasingly active in the Black Sea and especially confrontational with Ukrainian vessels.

When Russian forces took control of Crimea in 2014, they also seized Chernomorneftegaz, or CNG, a Crimea-based subsidiary of Ukraine’s state energy conglomerate Naftogaz. CNG had modest gas extraction ventures in the Black and Azov seas, particularly on the Crimean shelf, and was looking to expand operations.

“We have a lot of concerns about the Russians,” says Ponomarev. “This is why all of our investors would be insured by OPIC (the U. S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation). They specifically handle military and political risks, that is their core competence.”

Competitors

It might have helped Trident’s win in the tender that some of the company’s contenders were shrouded in controversy in the weeks leading up to the result.

In addition to Trident, only three other companies submitted a proposal: Texas-registered Frontera Resources, the Caspian Drilling Company (CDC) from Azerbaijan, and Ukrnaftoburinnya, a large Ukrainian gas producer of which the controversial Ukrainian oligarchs Ihor Kolomoisky and Pavel Fuchs are the ultimate beneficiaries.

Journalists with Schemes, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s investigative unit, revealed a number of problems with the contenders, especially the one-time favorite, Frontera Resources, which is allegedly a loss-making company with failing gas extraction ventures in Georgia and Moldova.

Its subsidiaries registered in Ukraine appear to have no assets and only two staff, according to Schemes. Frontera has not responded to requests for comment and phone calls go to a generic voicemail.

CDC, on the other hand, which is part of the State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR) has faced unproven accusations that its bid had ties to Moscow, something explicitly prohibited in the terms of the tender, and the company voluntarily withdrew its application.

“We will create some 2,000 local jobs, paying taxes in Ukraine. We operate in Ukraine and we will supply to Ukraine,” says Ponomarev, adding that Trident’s competitors for the bid are completely unprepared for the project.

According to him, if it is signed off, the Trident joint venture will open up Ukraine’s offshore gas market to foreign investors, benefiting Ukrainian energy security and the coastal economy.