Featured Galleries USUBC COLLECTION OF OVER 160 UKRAINE HISTORIC NEWS PHOTOGRAPHS 1918-1997

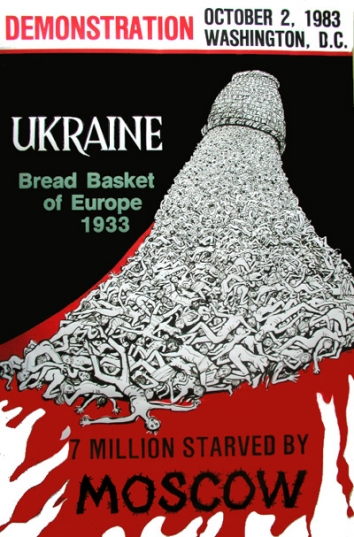

Holodomor Posters

Holodomor Posters

Welcome to a New World

COSA, Kyiv, Ukraine,

COSA, Kyiv, Ukraine,

June 09, Tue, 2020

Peter Kopka, Principal Expert and Strategic Adviser at COSA

Peter was the founder of the Analytical Division of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine. In 2003 he was the acting head of the Foreign Intelligence Service of Ukraine. Peter retired in 2004 in the rank of Major-General and until 2010 worked as first deputy director of the Institute of problems of national security of the National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine. Petro joined COSA in 2014 and since then he has provided expertise in regard to the methodology of research, as well as contributed into COSA’s enhanced political, economic and security risk analysis in the framework of widescale risk assessment, research and monitoring projects.

Plurality should not be posited without necessity

(Occam’s razor)

For more than two months now, the world has been living in a new reality, a reality not yet fully understood or verified, but its influence is no less strong for that – to the contrary, it is growing stronger and spreading wider, enveloping more and more aspects of the global society with each passing day.

Is this new world really all that new?

The structure of this new world is still too vague to draw any conclusions about what it will look like in the end, but, given the environment it has been developing in, it is already safe to say that COVID-19 has been distorting the existing global system and creating a less open one, where freedoms (in every sense of the world) are limited.

In this process, the pandemic has been and will remain nothing more than a catalyst for changes that were already noticeable in the global community in the late 2019. One could say that if the virus had not emerged, it should have been invented as soon as possible. For that matter, no one has yet proven that it was not.

Uncertainty will be the key (generic) characteristic of the new, post-pandemic world. Politics, economy, society, everything is going to be uncertain. And where there is uncertainty, instability follows with all the implications such a combination of probabilities can bring.

The basis for this, in turn, will be the global community’s doubt about the success of the worldwide operation to stop COVID-19, at least until a vaccine for it is created and passes clinical trials. Yet even then, there will remain the risk of new mutations that can appear at any moment and disrupt the status quo achieved by the society that will have overcome this current strain of coronavirus.

In all this, we should keep in mind that governments in some countries, like Brazil, for example, have been creating environments that are conducive to such mutations.

It will be this global negative anticipation that will become the latent factor determining the long-term agenda of humanity’s survival.

For now, in the near and mid-term, the policy that will remain prevalent in the world will be conflict-seeking in nature. The foundation of the new world order will still be the confrontation between the global and the national.

The Quality of Future Changes

The fact that the globalisation model prevalent in the world since the second half of the 20th century was no longer valid in the global reality of the mid-2000s was obvious long before the pandemic struck.

After 2008, the international climate was influenced by the fundamental contradiction between the new, pro-integration form of humanity’s existence, brought about by new technology such as the Internet and mobile telecommunications, and the old, fragmented substance. The form dictated new, globalised interaction, while the substance was still rife with old attempts to break the world into spheres of influence.

As a result, the anti-globalists led by Putin’s Russia have temporarily gained the upper hand, which is why the world is now permeated by nationalism founded on state egotism, the spread of which was initiated by Moscow in the mid-2000s and then taken up by the current US administration. The virus only served to escalate this confrontation.

This is a temporary phenomenon, however. Judging by the way countries have been fighting the pandemic, it is clear that the global community will have to unite in order to combat COVID-19 effectively and prevent new outbreaks. There has to be unity in this area at least.

On the other hand, it is less than likely that the world will come back to the previous model of mutually beneficial globalisation that was the main drive of societal development in the late 20th century and the early 21st. The new form of international interaction will be more careful and selective, so to speak. The quality of interaction between international entities will be influenced by yet another, “viral” factor.

An apt illustration of the way our globalised world has responded to the current threat is the situation in the European Union, the most successful integration project to date. The pandemic has shown that where fighting the virus and solving economic problems are concerned it is best for EU members to rely on their own strengths most of all.

In addition to causing political changes, the pandemic-related crisis will continue to suppress economic activity and deepen the discord between countries. Closing down borders and stimulating local vertically-integrated production breaks value chains and ultimately distorts the international price system.

Further down the line, such a negative influence will cause systemic changes, when the decline in capacity of the global economy will result in a deformed labour market and the weakening of international arbitration organisations. This includes all the possible implications of such changes.

In order to counteract negative trends, national governments will have to take decisive action to make their economies more controllable and efficient. To that effect, they may choose to concentrate strategically important production facilities within their borders.

As evidence in support of this version, we can look at the operation to merge two American defence enterprises, Raytheon Company and United Technologies Corporation, into Raytheon Technologies Corporation. The merger was closed on 3 April 2020 (it was officially announced on 9 June 2019).

This created one of the world’s largest aerospace and defence companies with approximate annual revenue of USD 74 billion and 195,000 employees.

The policy of saving strategically important industries forces governments to nationalise some of them. For instance, in Italy, this was done to save the national airline Alitalia.

Such efforts by governments are unlikely to increase efficiency but will probably help industries to stay afloat by means of taxpayer money. On the other hand, there is the risk of countries getting mired in total nationalisation of their economies. The longer the pandemic continues, the higher the probability of this risk turning into a real threat.

Speaking of risk, practice has shown that the current risk assessment system was inadequate long before the pandemic. Most market actors were certain that in case of any problems national regulators would always be there to help. Thus, if paternalism continues to hold sway in countries for some time, the inadequacy of this system threatens to reach global proportions. From there, the situation can easily devolve into financial bubbles and a repeat of the crisis of 2008–2009 on a larger scale.

All this creates a demand for a drastic change in our approach to risk assessment for risks associated with societal development, from a single individual to humanity as a whole.

Special attention should be paid to the main international actor, the state. The classic, conventional methodology of country risk assessment does not work in the new environment, because its foundational paradigm of the national government being the primary and independent source of such risks has become obsolete. In the new reality, a government can under certain circumstances turn into the object of influence exercised by actors beyond the country’s borders, which are becoming increasingly difficult to identify.

Some Conclusions

As we can see, the picture of our future looks rather bleak. However, the need for cooperation and teamwork to solve the most important problems remains urgent. How fast and how well the international system resolves the crisis depends, yet again, on our understanding of the nature of the new reality and the international community’s willingness to develop international relations in the new environment.

This is clearly the way to go, all the more so because there already are some practices on which the countries forming the international community can build. After the recession of 2008–2009, G20 managed to join their efforts not only to preserve but to strengthen the global financial system, which made the relatively fast recovery possible.

Finally, while the bipolar world was built on the principle of preventing a global war and the first three decades of the post-bipolar world were about developing the global economy, finance, and trade, the emerging world requires the international community to pay closer attention to global humanitarian issues. They could start with turning major international organisations such as the UN and the WHO, which have been mostly ornamental, into effective instruments able to solve intricate problems that will be increasing in number and complexity as time goes by.